Ordinarily it takes an entire team to score 300 runs. As a rule, 11 batsmen are required to compile a total widely regarded as the starting point of satisfaction, the cusp of hope. Often they fall short, succumbing for some paltry total and glaring at pitches, umpires and sometimes even balls and review systems as they depart. The meek may indeed inherit the earth but don't pit them against Dennis Lillee or Dale Steyn.

Ordinarily it takes a batsman an entire month to add 300 runs to his collection. So many things can go wrong: weather, pitches, confounded captains putting fieldsmen in the right places, poor light, drunken groundsmen, idiotic partners, probing flingers and so on and so forth. A batsman has one chance, 10 means of dismissal and 11 men set against him. Baseball hitters cannot be leg-before-wicket or stumped. And bowlers think they have a hard time of it?

A batsman scoring 300 runs in a single outing has to overcome all sorts of challenges. Time is one factor. For all except the most devastating players it is inclined to run out. Admittedly Viv Richards did once blast 300 before tea in a county match, but most of us can spend five hours over a hundred only for delight to be reduced by a message from the rooms saying, "Well done, but for goodness' sake, hurry up!" Or some such.

Energy is another factor. Cricket may look tranquil but an enormous amount of reserves can be spent running up and down the wicket, concentrating on every ball, striking the ball to the boundary, and all the while wearing armour and carrying a club. Fitness and strength are required.

A sturdy technique is also essential. Three hundred is not the realm of gamblers or lightweights. Command is not the purview of the loose living. A chancer might smack a hundred once in a while, but the odds are stacked against a long occupation. Domination demands the crushing of hope. High accomplishment is needed.

To score 300 in a Test match is another step again. It is the work of a lifetime expressed in a single innings. It tells of childhood aspiration and private practices in backyards, speaks of obsession and capacity. It is no small thing to belabour the best an opposing country has to offer so comprehensively that 300 notches have been accrued before the work has been complete. And do not forget that every batsman starts on zero, with the queasy feeling that produces; or that the bowlers are also representing their nation and trying to put their names in the books.

Even to reach 200 in Test cricket is a mighty feat. Sachin Tendulkar and Jacques Kallis are two of the greatest batsmen of the age. Between them they have played umpteen Tests, some of them against weak opponents and all of them on covered pitches, and still it took them deep into their careers to reach 200. Upon attaining that target, and filling that gap, they celebrated and acknowledged satisfaction intermingled with relief. And they were still many runs shy of joining the 300 club.

Although these batsman have had their chances, it's also important to be in the right place at the right time. Not even the greatest batsmen can score 300 unless the pitch is reliable. Indeed the pitch matters more than the quality of the opposition. Surprisingly few of the vast tallies have been scored against weak opponents. Perhaps teams declare earlier against them, or the runs are shared around. Of the five most recent 300s, three were scored against South Africa and two against Sri Lanka.

Test 300s are a product of their times as well as the ability and durability of the batsman. Most of the 24 triple-centuries have been scored in periods of friendly pitches and longer days. Indeed the graph charts the fluctuating balance between bat and ball. The majority were attained in two fertile spells for willow wielders.

No 300s were scored until 1930, whereupon Andy Sandham, a polished opening batsman from Surrey,

took a toll of a West Indian side still sorting itself out. Altogether five 300s were scored before the Second World War.

It is not quite accurate to describe scoring 300 as a once-in-a-lifetime achievement. Four batsmen have repeated the feat: three moderns and an old fellow called Don Bradman, a player given to cutting attacks to ribbons.

Only two triples were scored from 1946 to the end of the fifties, and those by two remarkable cricketers, Hanif Mohammad and Garfield Sobers. Nor were the sixties productive, with only Bob Simpson, Bob Cowper and John Edrich reaching the mark. That these doughty warriors made cricket's highest individual scores in an otherwise fertile decade tells a tale about the state of the game. It is hard to imagine any of them shopping in Carnaby Street or attending Woodstock or protesting about the Vietnam War or attacking the bowling.

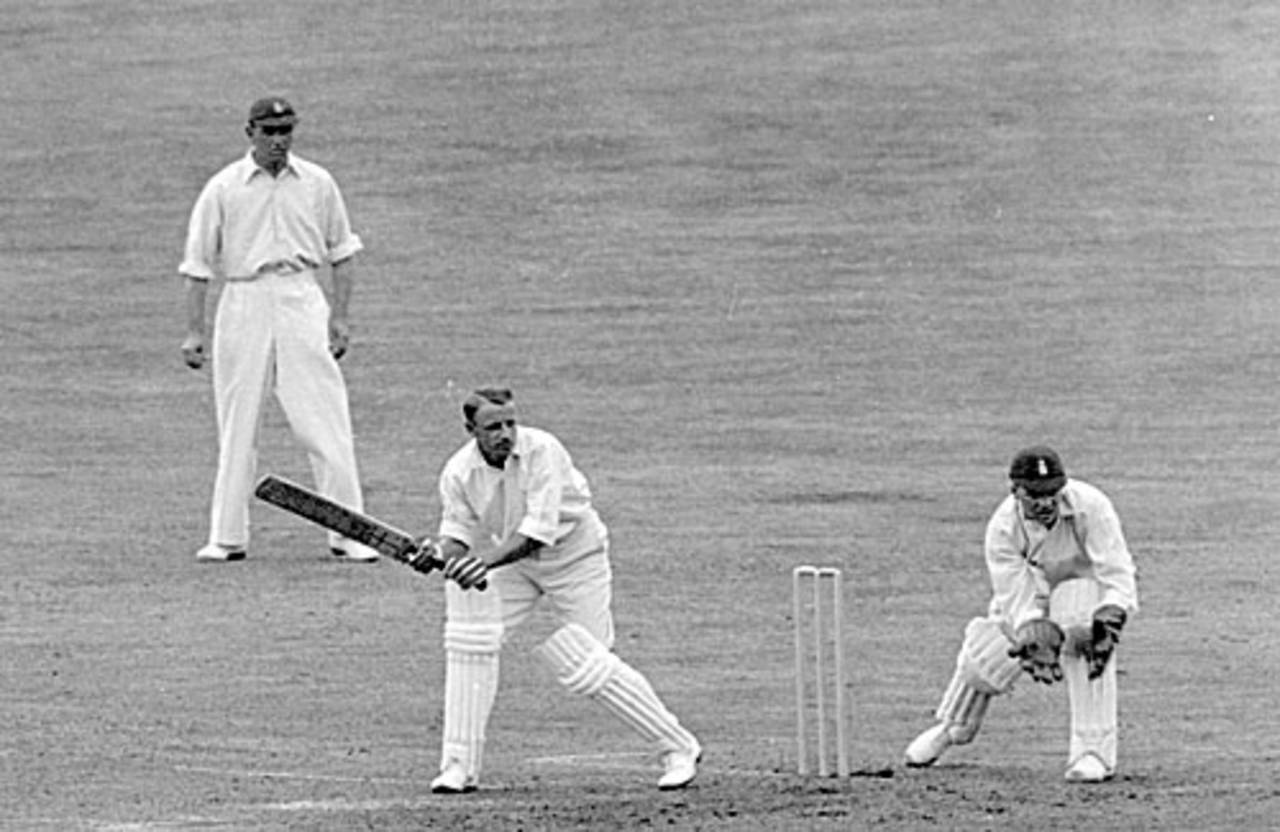

From 1966 to 1990 only one batsman reached 300, and he never again scaled such heights. Lawrence Rowe's stunning 302 against England

in Barbados in 1974 is remembered by all those privileged to see it. It seemed to herald the arrival of a great batsman. Alas, Rowe was dogged by poor health and bad eyesight, and lost his path, ending up almost as an outcast due to his willingness to tour South Africa in those dismal years.

After a barren 1980s caused by top-class pace bowling, especially from West Indies but elsewhere as well, the batsmen began to dictate terms again in the 1990s, with four players reaching 300: Graham Gooch, Mark Taylor, Sanath Jayasuriya and Brian Lara. Three of them opened the batting and three were left-handers (as far as batting is concerned anyhow), thereby setting a trend. Lara and Virender Sehwag were to join Bradman as double triple-centurions (it's starting to sound like a Big Mac), and eventually Chris Gayle, another left-hand opener with a stronger right hand, added his name to the list.

That Simpson, Cowper and Edrich made cricket's highest individual scores in the '60s tells a tale about the state of the game. It is hard to imagine any of them shopping in Carnaby Street or attending Woodstock or protesting about the Vietnam War or attacking the bowling

The three most interesting trends in cricket at present are the way lefties with dominant right hands are taking over batting, the part played by South African-born players in English cricket and the increasing importance of Indian expatriates in overseas cricket communities.

Students of the game will not be surprised to hear that the new century has been the most productive period of them all as far as heavy scoring is concerned. Of course many more Tests are played these days, so comparisons with the thirties are tricky. Overall nine triple-hundreds have been made, only one of them by an Australian, and that against Zimbabwe, none by England batsmen, and none by the still-virginal South Africa and New Zealand (Martin Crowe will not easily forget the loose shot played against Arjuna Ranatunga that cost him

a 300th run).

Not that reaching 300 is the be-all and end-all. Sehwag's greatest innings, surely, were the

unbeaten double-hundred against the Lankans and the

195 against the Australians. On the first occasion he stood almost alone against probing spin, and on the second he thrilled a packed Boxing Day crowd with a display of sustained power, eye and audacity.

Geography has played a part in this surge. Of the last 12 triples, three were scored on the Recreation Ground in Antigua, now supposedly defunct, and eight of the last 11 were collected in the subcontinent, the modern home of high scoring and statistics. Elsewhere the tussle between bat and ball is not so one-sided. It's hard to convince a youth busy with Facebook and Youtube that it's worth going to sit under a hot sun to watch not so much a worthy contest as a statistical exercise.

Whether Test cricket can survive this domination of bat over ball and the stalemates it is liable to produce is a topic for another day. Suffice it to say, for now, that the struggle between batsmen and bowlers is the essence of the game. Sport without spirit is tedious in the extreme, and deservedly doomed.

That is not to decry the extraordinary feats recognised in this column. Batsmen are not called upon to worry about the state of the game so much as the position of the match. They can only face the next ball. Test hundreds are celebrated for they are the stuff of dreams. As much can be told from the nervousness of batsmen as they negotiate the nineties. Don't speak to a cricketer about 0 or 99 for these are the most feared numbers in the game.

Double-centuries remain rare and confirm a batsman's stamina, skill and supremacy. To score a triple-century in the highest company is to become a batsman apart. After all it's been done only 24 times in 1999 matches and roughly 50,000 outings.

Peter Roebuck is a former captain of Somerset and the author, most recently, of In It to Win It