A good little'un

Gideon Haigh on Roy Fredericks, West Indies' bantamweight opener

Gideon Haigh

31-Jan-2006

Odd Men In - a title shamelessly borrowed from AA Thomson's fantastic book - concerns cricketers who have caught my attention over the years in different ways - personally, historically, technically, stylistically - and about whom I have never previously found a pretext to write

|

|

|

In November 1977, when Kerry Packer's World Series Cricket came to my home town of Geelong, my grandmother's flat overlooked the forecourt of the Travelodge Motel, the town's swankiest hostelry. From her balcony I watched the West Indian players milling about their minibus before embarking for Kardinia Park - giants in repose, but still exuding a predatory air: the towering presence of Lloyd and Garner; the lounging power of Richards and Greenidge; the limber athleticism of King and Julien.

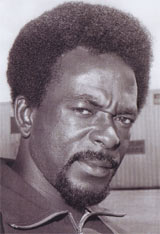

The one to watch, though, was Roy Fredericks, 163cm, not even 65kg, neat down to his closely-trimmed beard, bearing himself a little solemnly, perhaps even lugubriously. Heavens, he was so small, so unprepossessing, a bantamweight at best. He had played his first big cricket while still a clerk at the Blairmont sugar estate on the Berbice River, and would still have looked at home in collar and tie, behind a desk or a counter.

Yet it wasn't two years since, in a whirl of left-handed strokes, I had watched him lay waste one of Australia's greatest attacks on the world's fastest pitch. This cricket was quite a game, it crossed my young mind, if a good little `un could take down so many mighty big `uns. I'd soon experience the same sensation while admiring the balance and poise of Sunil Gavaskar and Gundappa Viswanath against Jeff Thomson. But Fredericks remained unique: with the power-to-weight ratio of a sports car, driving himself with foot to the floor.

That 169 in the teeth of Lillee, Thomson, Gilmour, Walker and Mallett at Perth took just three-and-a-half hours and 145 balls. It was the day that Jeff Thomson let go what remained for years cricket's fastest recorded delivery, at 99.68mph - to Fredericks, as it happens. No-one records the treatment meted out to the delivery, but if it did not vanish from a blazing bat at twice the speed it got off lightly: Thomson's first three overs cost 33; Fredericks' first fifty took 33 balls.

The shot that stands out in memory is the hook from Lillee's second delivery. In the World Cup final six months earlier, Fredericks had swung Lillee for six so violently as to lose the traction of his ripple soles and swivel into the stumps. Now he went even harder, as willingly as a cowboy throwing a punch in a Dodge City saloon.

Carried by the strong south-westerly at Lillee's back, the ball flew fine, entering the crowd just to the leg side of the sight screen. That makes it sound a little ungainly. In fact, a photo I've seen since of the shot shows him comfortably inside the line, upright and balanced. What he'd done, simply, was make the unconventional look entirely natural: something seen with only the best batsman. He'd also made a very great bowler look distinctly ordinary. This was Lillee's happy home hunting ground, where he'd slain the World XI four years earlier; now his first five overs cost 35, and West Indies were 91 when Fredericks' ersatz partner Bernard Julien was out after an hour.

|

|

|

It was a contest of two natures. The Australians knew no other way to bowl, and Fredericks favoured no other sort of batting. At Glamorgan, where he spent three seasons, he was known for his succinct expressions of intent: `I tink I'm agoin' to pelt some lash at de ball, man'. He had a voluminous backlift, but with reflexes honed by table tennis at which he had also represented Guyana was seldom late on his stroke; his follow-through was similarly expansive, feet often leaving the ground as he cut and pulled.

The WACA that afternoon was wreathed in smoke, the new City Centre skyscraper having caught fire. As Fredericks also smouldered, his bat threw off sympathetic sparks: for one spell of Gilmour's, the analysis read 1-0-22-0. In his book on the series, Frank Tyson recalls that his old captain Sir Leonard Hutton was a guest of the WACA during the match, and watched proceedings `with the amazement of the purist opening bat written all over his features'. Hutton's erstwhile rival Lindsay Hassett, then commentating for the ABC, was less circumspect, pronouncing it simply the best innings he'd ever seen in Australia.

Fredericks had not always played this way. On his debut in Australia seven years earlier, he had been rather more obdurate, making up for in guts what he lacked in flair. He was hit on the head by Graham McKenzie in Perth, coming back after a brief retirement, and by Alan Connolly in Sydney, not retiring at all; admiring Aussies nicknamed him Cement Head.

That did not change. He eschewed helmets, and once during World Series Cricket responded to being hit on the head by Len Pascoe with a contemptuous V-sign. He scorned chest protection; his sleeves, always buttoned to the wrist, were bare of guards. But it steadily became a kind of proclamation: Fredericks intent not on taking punishment but on dishing it out, usually in company with his like-minded protégé Gordon Greenidge.

Eight months after his plunder at Perth, he and Greenidge belted 192 in the first two-and-a-half hours of a Headingley Test, then an unbeaten 182 in two hours twenty minutes at the Oval; Snow, Willis, Underwood and Greig came alike. In what proved his farewell Test, he and Greenidge turned a low-scoring game on its head with 182 for the first wicket of the West Indies' second innings; Imran Khan and Sarfraz Nawaz were among the tamed.

Fredericks had officially `retired' from Tests by the day I glimpsed him across that street almost thirty years ago, wondering at the power he packed. But Jeff Thomson was among those for whom he couldn't finish quickly enough, finding him a redoubtable opponent even when WSC visited West Indies in 1979, by which time Fredericks was in his 37th year: `He was a thorn in our side, and we were always glad to see him go.' Thomson remembered; and, from my balcony of memory today, so do I.

Gideon Haigh is a cricket historian and writer