I imagine that for most cricket lovers the favourite player is the one who catches the eye at an early age, when the game is just taking hold. Later on you can relish the thought of going to watch Brian Lara, or Shane Warne, or Andrew Flintoff, but you can never quite recapture the breathless excitement of the moment you got hooked.

I had noticed cricket on the television, watched some of it, asked my parents what was going on. But things changed when I was nine, in the summer of 1966. England were struggling against West Indies. They were messing about with selection. They chose three captains (bettered only by 1988, when they had four). But one of the new caps was a bit different: Basil Lewis D'Oliveira.

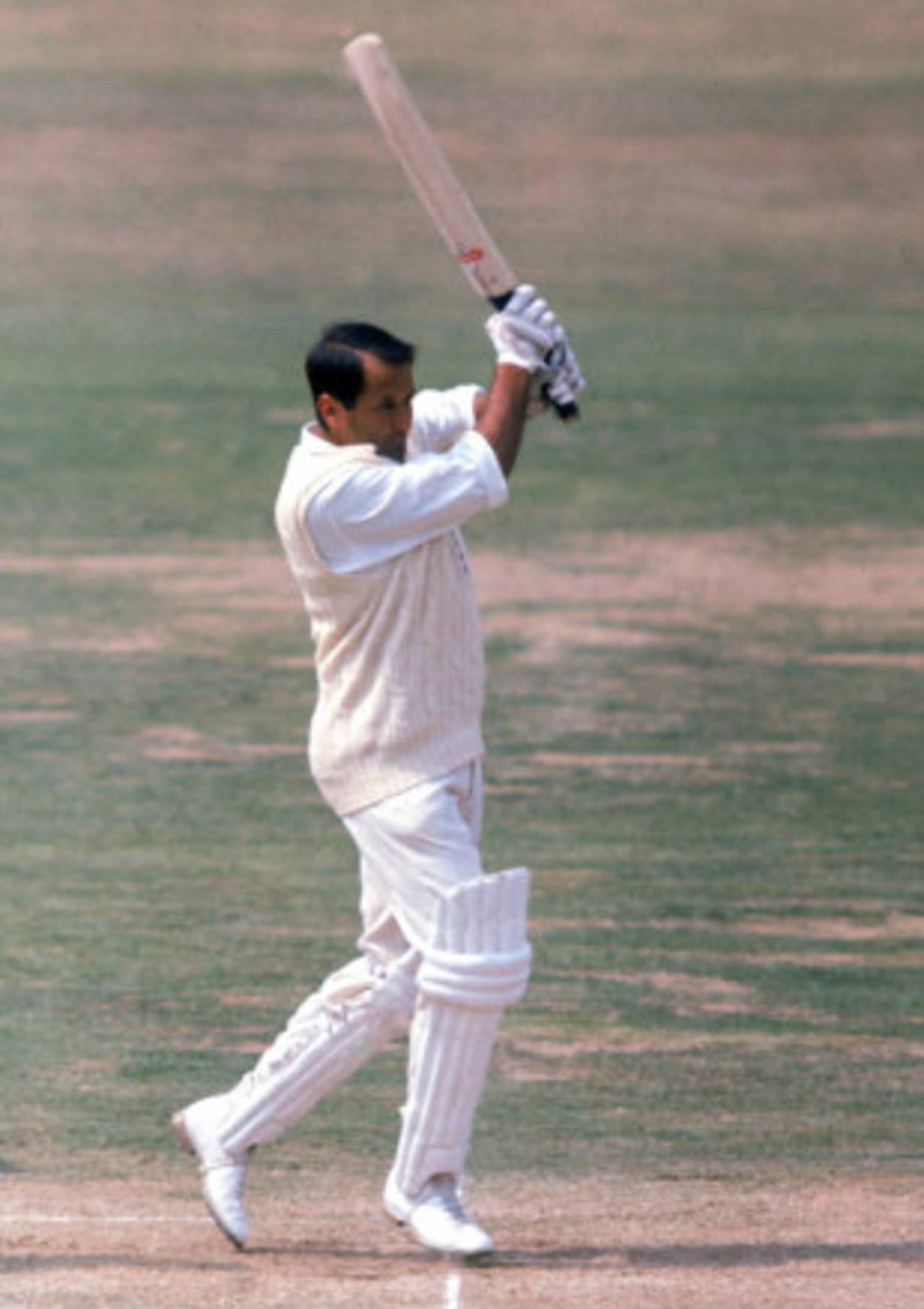

"Dolly" was a romantic figure - tall, dark and handsome, but with an air of mystery. This stemmed from his past: I knew he had come over from South Africa because he wasn't allowed to play there. My mother tried to explain why not, but it didn't sink in. But what I did notice was probably my first technical observation (apart from wondering why Jim Parks used to crouch down to keep wicket with his arms outside his pads, unlike all the other keepers I'd seen): D'Oliveira had almost no back-lift.

I was a martyr to tonsillitis at the time, which I suspect got worse when Tests were on, so I was able to follow D'Oliveira's first series closely. He scored 27 at Lord's before suffering a freakish run-out. But the shot that cemented Dolly's place in the pantheon came in the fourth Test, when he smashed Wes Hall - the fastest bowler in the world at the time - straight back over his head for six.

Much later I learned about the pressure D'Oliveira must have felt, representing millions of coloured South Africans. He had a few secrets. Unbeknown to the selectors, he could hardly throw the ball in the field after having smashed his arm in a car accident the previous winter. And then there was his age.

Ah, yes, his age. When I found out about that, Dolly went up even higher in my youthful estimation. When he joined Worcestershire, he said he was born in 1934, which meant the England selectors thought he was a reasonably youthful 31 when they called him up. It was some time before he owned up. He had felt, probably rightly, that England would not have blooded someone approaching 35. Even that is not quite the end of the story. In his autobiography D'Oliveira wrote: "I can assure you I'm a little older than my birth certificate states... If you told me I was nearer 40 than 35 when I first played for England, I wouldn't sue you for slander." I always thought the Playfair Cricket Annual went a little too far in 1979, though, when it gave his year of birth as 1031.

Dolly remained a fixture in the Test team for six years, until he was 41 (or 38, or 46, or possibly 941). For all that time he was the only player I really wanted to succeed. I was rewarded in 1970 when he made the first century I ever saw live (105 for Worcestershire against Surrey at the Oval, since you ask).

Two years before that, he made another mark in cricket history by becoming the first Test player to speak to me. Nestled on the grass behind the boundary boards at the Oval on my first day of Test cricket in 1968 - sadly, a couple of days after D'Oliveira's famous 158 at the ground - I was at first delighted, then rather alarmed, as Dolly lumbered towards me, chasing a ball to the boundary. He just failed to stop it, overran the ball, and carried on into the crowd, his boot spiking a neat hole in one of my lunchtime sandwiches as he did so. "Sorry, son," he said as he returned to the field, leaving me even more in awe than before. I kept the evidence for ages, until my Mum threw away the star exhibit of my burgeoning cricket museum, saying it was turning green.

Batting like D'Oliveira was never very likely, so for a while I tried to bowl like him: both arms swooping upwards just before delivery, then a rhythmical, circular sweep of the bowling arm. When he did it, it kept the runs down and broke partnerships at vital moments of Ashes series. My efforts were rather less spectacular, but they lasted longer than later attempts to bowl like Jeff Thomson.

If things had been different, Dolly might have been pulverising bowlers for South Africa in the 1950s rather than doing wonders for England in the sixties. I began to have some idea of the hurdles he overcame just to play club cricket in England, never mind county or Test cricket. Throughout he seems to have remained the smiling, modest bloke who apologised when he stepped on my sandwiches. I do know now that off the field he liked a drink, sometimes got a bit loud, and that he didn't cover himself with glory on his first tour with England, to the West Indies in 1968.

But I don't care. D'Oliveira's place in history is secure: he was the man who, inadvertently, made the sporting world at large aware of what was wrong with apartheid. And he cemented one small boy's love of cricket.

Steven Lynch is deputy editor of the Wisden Group