Beating big brother

Defeating Australia was just one of the many memorable things for New Zealand in this game at Lancaster Park

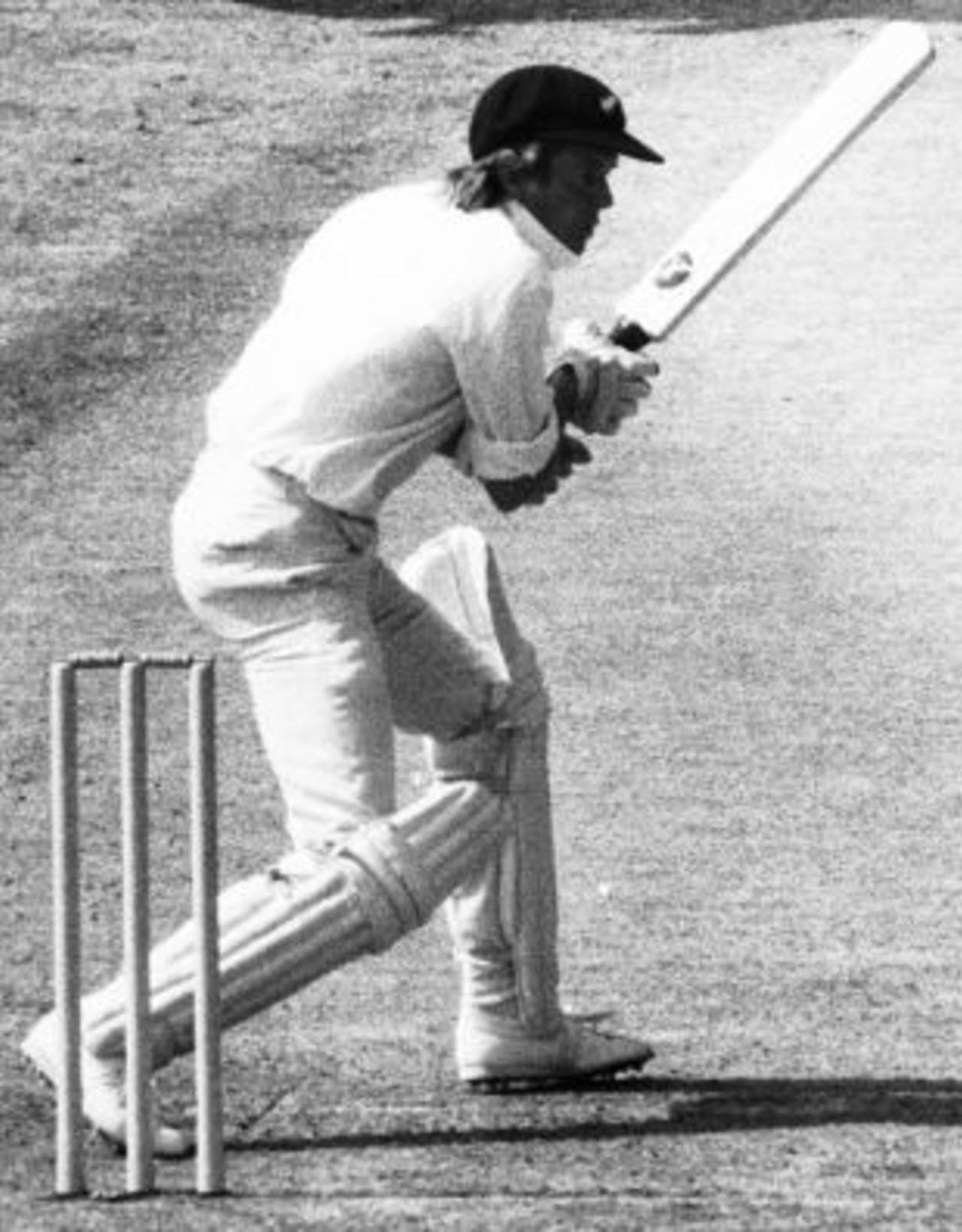

Glenn Turner

18-Jul-2011

Glenn Turner: two hundreds in the game • Getty Images

We all often use the word belief. I am not given to extravagant reaction to success or defeat, but I will concede that our win against Australia at Lancaster Park in 1974 helped our cricket come of age. It gave us that belief. It also gave a boost to the game in New Zealand at that time.

Of all the first wins against all the teams, this one was the most special. It came in front of our mob - and what atmosphere the 15,000 Canterburians created over those five special days. That I got a hundred in each innings on a difficult pitch, and that I stayed not out in the chase, made it satisfying from a personal point of view. Importantly no team dominated the game for too long, which made for engrossing Test cricket.

Every time a partnership would develop, the bowling side would strike back with two-three wickets. In a match in which 259 and 223 were the highest and lowest scores, Australia's last five put on 95 and 117 to add to the tension. Because we were the underdogs, even though we got into positions that were stronger than they had got into, there was not enough belief that we could go and win it.

Further drama was provided when Ian Chappell, Australia's captain, had a long verbal go at me. It was probably understandable, since it looked like little old New Zealand were going to beat Australia. There was no way he wanted to be associated with that. After all we were the side they had bowled out for 42 and 54 at the Basin Reserve in 1946, our first and only Test against Australia, until they condescended in 1973-74 to have us over for a proper Test series and a return leg.

By now we were an improved side. Over the last five years we had won a series in Pakistan and drawn in India and the West Indies. On our trip to Australia earlier in 1973-74, we were only eight wickets from a win on the completely washed-out final day of the Sydney Test. That told us Australia were beatable.

All the determination to beat them didn't make us poor hosts. When we came to Christchurch after the Wellington runathon, the weather wasn't great, and we only had one practice strip available for pre-Test practice. We gave that to the Australians. How things have changed now. As it turned out, you couldn't have been too prepared for the pitch, which would not settle down throughout the match.

I remember expressing my disappointment at how green the pitch was. I suppose others could hear it too. Bevan Congdon, the captain, gave me a bit of a sermon because he didn't think that helped the motivation of the team. I was just stating a fact, as far as I thought.

Earlier he had asked me what we should do if we won the toss, and I had told him, "You needn't worry because you couldn't win a toss." He did. And he followed local man Brian Hastings' advice to put Australia in.

The start was delayed until after lunch, but we knew we had made the right decision when we had them down at 128 for 5 at stumps. However, Ian Redpath, the equivalent of what people here perceived, and sometimes looked down upon, as an English pro, scored 71 to help them past 200. I know the Aussies were even more prejudiced against the "bloody Poms" - the batsmen who grafted and eked out a living. Here, though, the man who played like a Pom was going to be crucial - he scored two half-centuries.

When we batted, it was a question of trying to accumulate runs and trying to survive. I played and missed a heck of a lot in the first innings; it was one of those tracks. It was quite frustrating. I prided myself in knowing where my off stump was, in being a good judge of letting the ball go. I certainly didn't show that much in that first innings. However, I decided I would suffer my embarrassment. I told myself, "Damn it, I must fight through it, and even if it takes me all day I'll keep going and see if I can come right."

I went 99 not out overnight. I had had a previous experience of ending a day 99 not out, in Dacca against Pakistan in 1969, but this time I took more than half an hour to get the 100th run. I was disappointed I could add only one to my hundred, and we lost our last five wickets for 42 to end up with just a 32-run lead.

"A guy passing the ground in his car heard it on the radio, parked outside the main gate, left the motor running, and rushed into the ground to see the final runs. That is an indication of how much it meant"

Having let things go a bit from a dominating position, we relied on our bowlers to bowl Australia out again. The start of the Australian innings was one of the most exciting and elating periods of play I've ever experienced. It was a Sunday, and close to 15,000 spectators had turned up. I became less aware of the crowds as my career went on, but that day was special. Christchurch crowds can be parochial, which means you need to be playing for either Canterbury or New Zealand to get support there, but they could support their team all right.

It was all pretty charged up when the locals sensed that we had a chance to beat Australia for the first time. With the stands right in at Lancaster Park, the reverberation of sound coming back out into the middle was deafening. And we gave them a lot of reason to make that sound.

Keith Stackpole, going through a wretched run of form, was taken early by left-arm seamer Richard Collinge.

We knew Ian Chappell made too many preliminary movements in the crease, especially across the stumps, and especially when he just came in. We knew the best bowler to exploit that would be Collinge. However, if you start to bowl deliberately at leg stump, you can be hit for some. All you can do is put on the bowler who has the best chance to exploit the weakness, and just hope that it happens. And it happened. Chappell lost his leg stump. The roar from the crowd sent shivers down my spine.

We always considered his brother, Greg Chappell, the better batsman, but he too could be a bit flashy. He went to force [Richard] Hadlee outside off, and got a nick. The crowd erupted with a roar. It was as if they were in a wilful state of hypnosis. But the ball had yet not been caught. To me, fielding at cover because of a hand injury, it was almost like a slow-motion replay. Young Jeremy Coney completed that crucial catch, and Australia were 33 for 3.

The "English pro" got stuck in again, and with contributions from Ian Davis and Doug Walters, they set us 228 to get. They just couldn't accept what was happening. They couldn't lose to New Zealand. It was obviously hurting them.

They got stuck in. They were giving it their best shot. The crowd was still charged up, as were the Aussies, and the tension surrounding the game on and off the field was as great as I had experienced.

I was not overawed by them, though. During my years of professional cricket in England, I realised that although the Australians were talented players, tactically they were a bit naïve when compared to those who played full-time on the English circuit. You might find this arrogant, but that was the reality then. It has changed now obviously. From that point of view, I was not overawed one little bit.

I felt much better batting this time around, and was more certain of the whereabouts of my off stump. However, Congdon's run-out left us at 62 for 3. Had we not won the match, more attention would have been focused on that, and it could have assumed greater, perhaps tragic, proportions. As it turned out, Hastings and I added 115 for the fourth wicket, which calmed everything down.

The partnership itself wasn't quite as calm. Towards the end of the second-last day, Hastings hit Ashley Mallett over wide mid-on, one bounce into the stands. It pitched about five or six metres inside the fence, but some spectators signalled sixes. Bob Monteith, the umpire, signalled six too. I said to Bob, "Did you lose sight of that, Bob? It landed well inside." He was about to change his signal from six to four when Ian Chappell sprinted up from slip to abuse him.

I intervened - you could call it that - by letting him know that it had all been sorted out. Then he set about me as well. The language continued, and I just walked away. When I got down to the other end in the next over, he had another crack at me. Normally if you play and miss, you would expect a few choice words, but when it is one sentence after another highly abusive sentence, it is taking it too far. He made reference to the fact that he would sort me out afterwards. I don't believe you go to office and expect to be abused. I asked for an apology, but of course it wasn't forthcoming.

The series took an unsavoury and regrettable turn then, but the next day was to savour, for us and the whole country. We needed 54 with six wickets in hand, yet a big crowd turned up because they wanted to be witness to our first Test win against Australia. Apparently a guy passing the ground in his car heard it on the radio, parked outside the main gate, left the motor running, and rushed into the ground to see the final runs. That is an indication of how much it meant.

As told to Sidharth Monga