Against all odds

Martin Williamson looks at the players who have overcome physical obstacles to play the game

Martin Williamson

13-Jun-2006

Different people have different pain thresholds. While some cricketers gain reputations for collapsing with the merest niggle, others overcome obstacles which would leave the average person incapacitated to forge careers in the first-class game. We look at a selection of players who have beaten the odds

|

|

|

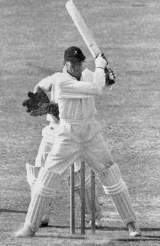

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Hutton was the best young batsman in the game and a year earlier had set the record for highest Test score (364 v Australia). But in March 1941, he injured his left arm so badly in a gym during commando training that three bone grafts were needed to repair the damage done by the compound fracture. He was in hospital for eight months before he was finally discharged, his left arm weakened and some two inches shorter than the other. However, he set about restoring the strength to the injured arm, and by 1943 he was making plenty of runs in the Bradford League. While many argued he was never quite the same player again - he lost the ability to hook and pull - he went on to become one of the leading batsmen in the decade after the war.

Nawab of Pataudi

Contrary to what many think, Pataudi did not lose the sight of his right eye in a car accident in 1962, but he did suffer serious injury which left him with double vision. He tried batting normally, but found that he was seeing two balls. He then experimented with an eye patch, but the loss of light in one eye affected the other one. His compromise was to pull his cap down over his right eye, so in effect he was only using on his left one. He said he found playing pace easier than slow bowling, as he found spinners' flight hard to judge. It did not do him too much harm as 40 of his 46 Tests were played after the accident. Others have coped with playing with one eye. Buster Nupen (South Africa) lost an eye in rioting in 1922 but took 11 for 150 against England in 1930-31, while Ranjitsinhji and Colin Milburn both made brief comebacks after being blinded in one eye.

Contrary to what many think, Pataudi did not lose the sight of his right eye in a car accident in 1962, but he did suffer serious injury which left him with double vision. He tried batting normally, but found that he was seeing two balls. He then experimented with an eye patch, but the loss of light in one eye affected the other one. His compromise was to pull his cap down over his right eye, so in effect he was only using on his left one. He said he found playing pace easier than slow bowling, as he found spinners' flight hard to judge. It did not do him too much harm as 40 of his 46 Tests were played after the accident. Others have coped with playing with one eye. Buster Nupen (South Africa) lost an eye in rioting in 1922 but took 11 for 150 against England in 1930-31, while Ranjitsinhji and Colin Milburn both made brief comebacks after being blinded in one eye.

|

|

|

That Melville even made it on to the field was a triumph in itself. He suffered a serious car accident before he arrived at Oxford University which left him with three fractured vertebrae and a lifelong back problem. While there he suffered from knee problems and missed most of the 1932 season - when he was captain - after breaking his collar bone in a collision with his fellow batsman. He also had permanently bruised hands because of the way he held the bat, and had to have special padded gloves made for him. During the war a bad fall while training with the South African forces in the war caused a recurrence of his back trouble and for nearly a year he was in a steel jacket. He returned to lead his side to England in 1947 where he made hundreds in his first three Test innings but only played once more after that series.

Harry Lee

Lee finally made his mark in the Middlesex side in the days before the start of World War One (WW1) but within months he had been shot in the leg during the hostilities at Neuve Chapelle and lay for three days between the lines. He was reported dead, and a memorial service was held. It turned out he was in German hands, but so bad were his injuries that he was repatriated as a hopeless case. Despite a shortened and withered left leg, he became a permanent fixture in the county side and made one Test outing in 1931. He had also survived another near miss when, in 1917, the ship he had been booked on to travel to India was torpedoed just out of Plymouth.

Lee finally made his mark in the Middlesex side in the days before the start of World War One (WW1) but within months he had been shot in the leg during the hostilities at Neuve Chapelle and lay for three days between the lines. He was reported dead, and a memorial service was held. It turned out he was in German hands, but so bad were his injuries that he was repatriated as a hopeless case. Despite a shortened and withered left leg, he became a permanent fixture in the county side and made one Test outing in 1931. He had also survived another near miss when, in 1917, the ship he had been booked on to travel to India was torpedoed just out of Plymouth.

|

|

|

Appleyard came late to cricket - he was 26 when he made his county debut - and after one full season he was diagnosed with pleurisy, but it soon turned out to be tuberculosis, at the time a potential killer (George Orwell had died of the disease the year before). Appleyard spent five months immobile in bed in hospital, during which time he had some of his lung removed, before learning how to walk again. Some questioned if he would live, almost none doubted that his cricket career was over. But he bounced back so successfully that two months after his comeback for Yorkshire he made his Test debut. He played nine times for England before a shoulder injury ended his career for good in 1958. His remarkable story is told in Stephen Chalke's outstanding No Coward Soul. Two other outstanding international cricketers - George Lohmann and Archie Jackson - died very young after contracting TB.

Nari Contractor

One of the bravest comebacks, Contractor's injury left him teetering on the brink of death. Struck on the side of the head by West Indies fast bowler Charlie Griffiths, Contractor, India's captain, suffered a fractured skull and underwent two emergency operations to save his life. A number of players involved in the match gave blood. Contractor refused to take medical advice to retire, and despite a metal plate in his skull, he played again, but not for India. The selectors, he later claimed, were afraid of what might happen were he to be hit on the head again. In 1971-72, Graeme Watson was hit in the face by a Tony Greig beamer and needed 40 pints of blood and heart massage to bring him through.

One of the bravest comebacks, Contractor's injury left him teetering on the brink of death. Struck on the side of the head by West Indies fast bowler Charlie Griffiths, Contractor, India's captain, suffered a fractured skull and underwent two emergency operations to save his life. A number of players involved in the match gave blood. Contractor refused to take medical advice to retire, and despite a metal plate in his skull, he played again, but not for India. The selectors, he later claimed, were afraid of what might happen were he to be hit on the head again. In 1971-72, Graeme Watson was hit in the face by a Tony Greig beamer and needed 40 pints of blood and heart massage to bring him through.

|

|

|

Greig had his first epileptic fit during a tennis game when he was 14, but he learned to successfully control his epilepsy with medication and self management, and few even knew about it for much of his career. But he collapsed on the field on his debut Eastern Province in 1971-72 - he said it took six or seven team-mates to hold him down - and the public were told he had sunstroke. He suffered another fit at Heathrow airport on return from the 1974-75 Ashes series, but his affliction only became public in 1978. "I am proud to have achieved so much despite such a handicap," he later wrote. More recently, Jony Rhodes was another who suffered from epilepsy.

Athol Rowan

A biltong-chewing medium-pacer before the Second World War, Rowan's left knee was shattered by the recoil from a gun in North Africa. He was left in permanent pain and unable to put his full weight on his front foot, and to compensate took up offspinning. Almost always in pain and with a distinct limp, he won his place on the 1947 tour of England after playing Test trials in leg irons. In 1949-50 his knee collapsed while playing for Transvaal against the Australians, and in 1951 he again broke down while in England, so much so that South Africa summoned a replacement. But Rowan was not to be bowed, and fought his way back into the side for the final Test before his knee again gave way so badly that even the courageous Rowan had to admit defeat.

A biltong-chewing medium-pacer before the Second World War, Rowan's left knee was shattered by the recoil from a gun in North Africa. He was left in permanent pain and unable to put his full weight on his front foot, and to compensate took up offspinning. Almost always in pain and with a distinct limp, he won his place on the 1947 tour of England after playing Test trials in leg irons. In 1949-50 his knee collapsed while playing for Transvaal against the Australians, and in 1951 he again broke down while in England, so much so that South Africa summoned a replacement. But Rowan was not to be bowed, and fought his way back into the side for the final Test before his knee again gave way so badly that even the courageous Rowan had to admit defeat.

|

|

|

Chandra was stricken by polio at the age of five but turned the handicap to his advantage with an indomitable spirit and with a withered right arm, he became one of the great leg-break bowlers of all time. He sent the ball down at virtual medium pace - quick enough to once hit a surprised Griffith with a bouncer - bowling googlies and top-spinners with his emaciated right arm, although he sometimes suffered from being used as a stock rather than an attacking bowler. Understandably, his batting was poor, and he fielded and threw with his left arm.

Denis Compton

In the days before footballers' metatarsals dominated the headlines, Compton's knee was perhaps the most famous sporting body part. Injured in 1938 during his time as a footballer with Arsenal, his knee became more problematic from the late 1940s, and by the mid-1950s Compton was almost permanently disabled, relying on his brilliance with the bat to compensate. In 1955 his kneecap was removed (it is now in a biscuit tin in the Lord's archives) and a leading surgeon, examining X-rays, said: "This man will never walk again." But Compton, in great pain, battled back, returning to the England side for the final Test of 1956. His career still ended prematurely in 1958, but at least he had gone out on his terms.

In the days before footballers' metatarsals dominated the headlines, Compton's knee was perhaps the most famous sporting body part. Injured in 1938 during his time as a footballer with Arsenal, his knee became more problematic from the late 1940s, and by the mid-1950s Compton was almost permanently disabled, relying on his brilliance with the bat to compensate. In 1955 his kneecap was removed (it is now in a biscuit tin in the Lord's archives) and a leading surgeon, examining X-rays, said: "This man will never walk again." But Compton, in great pain, battled back, returning to the England side for the final Test of 1956. His career still ended prematurely in 1958, but at least he had gone out on his terms.

|

|

|

Fred Titmus

Offspinner Titmus was one of England's leading allrounders for half-a-dozen years before he suffered a gruesome accident while on tour in the Caribbean in February 1968 when four toes on his right foot were severed by an outboard motor. He was told that had his big toe been cut off then his career would have been over, but remarkably he was playing again within weeks, and he finished the 1968 season with 111 wickets. He even made four more Test appearances in 1974-75, although he suffered from knee trouble as a result of his remodelled run-up. Titmus received £98 compensation for the loss of his toes.

Offspinner Titmus was one of England's leading allrounders for half-a-dozen years before he suffered a gruesome accident while on tour in the Caribbean in February 1968 when four toes on his right foot were severed by an outboard motor. He was told that had his big toe been cut off then his career would have been over, but remarkably he was playing again within weeks, and he finished the 1968 season with 111 wickets. He even made four more Test appearances in 1974-75, although he suffered from knee trouble as a result of his remodelled run-up. Titmus received £98 compensation for the loss of his toes.

Other players who overcame disability to play first-class cricket

Arthur Denton (Northants) - lost part of his leg in WW1 and had to bat with a runner

Jim Stewart (Northants) - had his big toe amputated

Graham Dowling (New Zealand) - had the second finger of his left hand amputated after injuring it wicketkeeping. He went on to captain New Zealand

Chuck Fleetwood-Smith (Australia) - switched to bowling left-handed after breaking his right arm at school

George Parr (Nottinghamshire) - deaf

Azeem Hafeez (Pakistan) - born with two fingers missing off right hand but became an international left-arm quick bowler

Frank Chester (Worcestershire) - became leading umpire after losing an arm in WW1

Trevor Franklin (New Zealand) - shattered leg when run over by a motorised luggage trolley at Gatwick airport in 1986. He returned to score a hundred at Lord's in 1990

Arthur Denton (Northants) - lost part of his leg in WW1 and had to bat with a runner

Jim Stewart (Northants) - had his big toe amputated

Graham Dowling (New Zealand) - had the second finger of his left hand amputated after injuring it wicketkeeping. He went on to captain New Zealand

Chuck Fleetwood-Smith (Australia) - switched to bowling left-handed after breaking his right arm at school

George Parr (Nottinghamshire) - deaf

Azeem Hafeez (Pakistan) - born with two fingers missing off right hand but became an international left-arm quick bowler

Frank Chester (Worcestershire) - became leading umpire after losing an arm in WW1

Trevor Franklin (New Zealand) - shattered leg when run over by a motorised luggage trolley at Gatwick airport in 1986. He returned to score a hundred at Lord's in 1990