'You can't be taught to inspire people. You have to be born a captain'

Former South Africa captain Ali Bacher talks about his series in charge against arch-rivals Australia, and the art of leadership

Interview by Crispin Andrews

02-Apr-2018

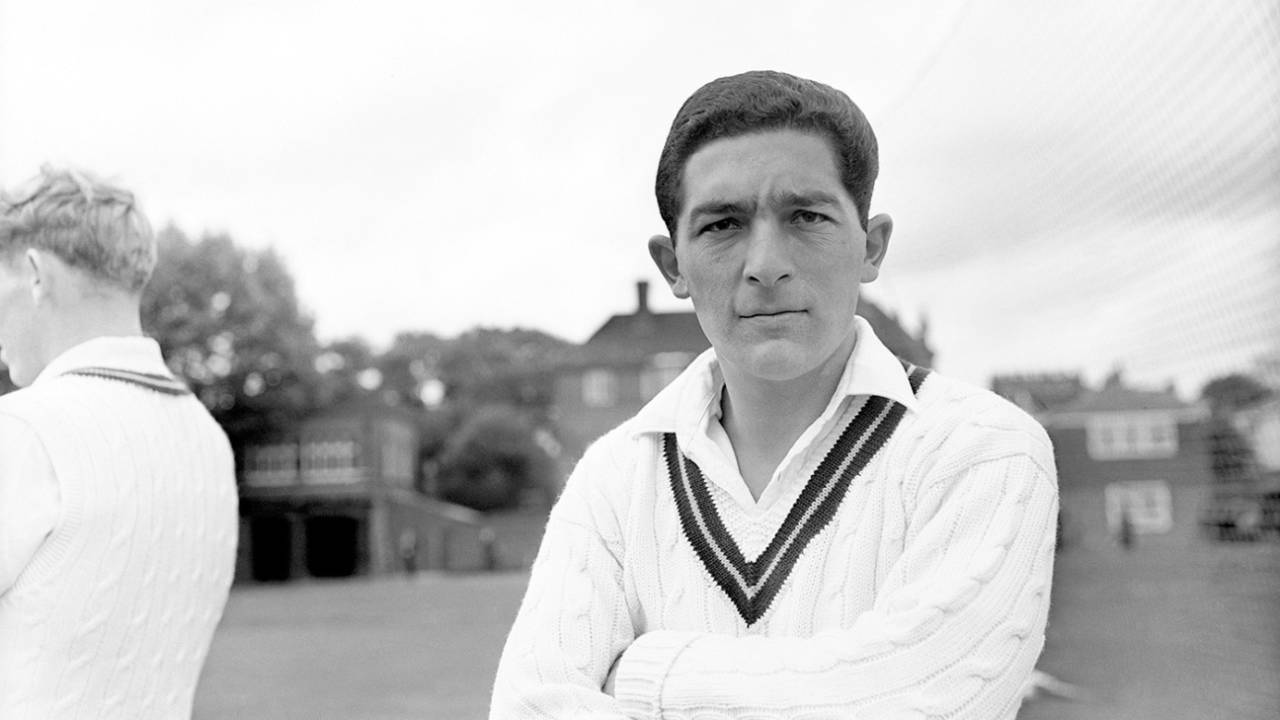

Ali Bacher in 1965: "The ability to motivate people, to stay calm, lift and inspire players is in your genes" • PA Photos/Getty Images

Ali Bacher was South Africa's cricket captain when the country was banned from international cricket in 1971. After retiring, he was CEO of the South African Cricket Union during their years of isolation, and was instrumental in organising the rebel tours, where teams of English, West Indian, Sri Lankan and Australian cricketers played unofficial internationals against South Africa sides. In 1990, when apartheid began to collapse in South Africa, Bacher lobbied for the formation of one body to oversee all cricket in the country. He managed the South African team on their first tour, after they were readmitted to international cricket, to India, in November 1991.

What is the biggest difference between modern-day captaincy and when you played?

I'm amazed at the back-up support today's captains have. The personnel accompanying the touring teams. Some, like England, have as many trainers, coaches and physios as actual players.

I'm amazed at the back-up support today's captains have. The personnel accompanying the touring teams. Some, like England, have as many trainers, coaches and physios as actual players.

When I was captain of South Africa, we would have a team talk before a Test match, which would be concerned with how to get the balance right in the game ahead.

What aspects of modern captaincy do you question?

First of all, by and large, fast bowlers bowl without a third man now. I remember watching a Test match in South Africa in the 1990s. It was the second day and the opposition got almost 400 runs. Peter Pollock, then a selector, was watching the game and he went to the scorer and found out that had there been a third man to the quicks all day, that fielder might have saved 80 runs.

First of all, by and large, fast bowlers bowl without a third man now. I remember watching a Test match in South Africa in the 1990s. It was the second day and the opposition got almost 400 runs. Peter Pollock, then a selector, was watching the game and he went to the scorer and found out that had there been a third man to the quicks all day, that fielder might have saved 80 runs.

In 1998, when South Africa toured England, we tried to get some former South African players who had played county cricket to talk to the team. Clive Rice, who captained Richard Hadlee at Nottinghamshire, said that when Hadlee came on to bowl, he would tell Rice: "I'll have a third man, a straight mid-off, you can do the rest."

When the quicks are bowling, there are many overs where captains don't apply pressure, particularly when a new batsman comes in. The field hardly changes. Mid-off not brought to silly mid-off; third man, if there is one, stays down on the fence rather than being brought in to slip.

When I changed the field, it was always to put pressure on the batsman. Everybody is nervous, although with some it might not show, but they are. After they've scored 20 or 30 runs, they start getting back to normal.

Secondly, why is it that left-arm fast bowlers bowl without leg-side catchers? Even with the new ball, even when they're swinging it in mostly, they still have a predominantly off-side field. Former great Australian left-arm pace bowler Alan Davidson bowled with a leg slip, leg gully and a bat pad. He would bowl an off-and-middle line and swing the ball in late.

Thirdly, the way captains set the field to tailenders. I remember Mark Waugh batting against South Africa, and again, when England played South Africa in 1998. Both times a recognised batsman and a tailender just hung in there. When the rabbit faced, the field was pretty much the same. That was two games South Africa should have won, but at no time did the captain put those batsmen under pressure.

Who is more important, the captain or the coach?

In cricket, the captain is the most important person on the field. I question how relevant a coach is. In football, the coach takes people off the field, replaces them with substitutes, changes tactics and formations. He's in charge, not the captain. It's the same in rugby.

In cricket, the captain is the most important person on the field. I question how relevant a coach is. In football, the coach takes people off the field, replaces them with substitutes, changes tactics and formations. He's in charge, not the captain. It's the same in rugby.

From left: Steve Tshwete, Geoff Dakin, Krish Mackherdhuj and Ali Bacher at the ICC meeting at Lord's where South Africa's return to international cricket was announced•Getty Images

In cricket, it's the captain who makes the decisions. The captain is on the field for the whole day. He can't shout to the coach on the sidelines about what to do next, or if things aren't going his way. It is the captain who the players look to and who has to come up with the ideas.

How did you captain teams?

I always wanted to be captain so I could help people. My belief was that of the 11 players in your team, there would be eight or nine who were in top form. Before a game, I preferred to focus on the two or three who weren't feeling so confident. Maybe they were new to the team and yet to establish themselves, or they were having a bad run. I would subtly focus on these players, try and lift them, reduce the pressure on them without them knowing.

I always wanted to be captain so I could help people. My belief was that of the 11 players in your team, there would be eight or nine who were in top form. Before a game, I preferred to focus on the two or three who weren't feeling so confident. Maybe they were new to the team and yet to establish themselves, or they were having a bad run. I would subtly focus on these players, try and lift them, reduce the pressure on them without them knowing.

A captain needs to be able to handle people differently. To get the best out of Graeme Pollock, you just praised him, made a fuss of how great he was. Graeme really was great, and he liked to hear how much he was appreciated.

I had a different approach for Don Mackay-Coghill, a left-arm quick bowler in my Transvaal team in the late '60s and early '70s. Don should have played for South Africa. He took more wickets than anyone for us. To get Don performing at his best, you just needed to stir up a bit of aggro. I'd tell him that one of the opposition batters thought that he was no bloody good. Then his blood pressure would go up, and he'd bowl better!

How much easier is captaincy when you have a side as good as your South African team was?

There was so much talent in that side. In the second innings of the third Test [Johannesburg, 1970], I was able to change the batting order so that Eddie Barlow, who'd been batting five, moved up to open and Trevor Goddard, who'd been opening, went down to nine. Mike Procter, who two years later would go on to score a world-record six consecutive first-class hundreds, was down at eight. We had some really good young players just starting to make their mark.

There was so much talent in that side. In the second innings of the third Test [Johannesburg, 1970], I was able to change the batting order so that Eddie Barlow, who'd been batting five, moved up to open and Trevor Goddard, who'd been opening, went down to nine. Mike Procter, who two years later would go on to score a world-record six consecutive first-class hundreds, was down at eight. We had some really good young players just starting to make their mark.

There was a lot of experience in that team. Whichever opposition player we were talking about, someone in our team would have played against him and have some ideas. Everybody had a good idea. I've heard Steve Waugh say the same thing about team meetings.

What characteristics does a good captain need?

You have to be a good motivator. Not necessarily the best player. Mike Brearley wasn't the best batsmen but he could lift people. Steve Waugh's thinking about the game was unbelievable. He had a cricketing brain second to none. Never allowed a game to roll on. If the game wasn't going his way, he'd do something to change it. Alter the momentum on the field somehow.

You have to be a good motivator. Not necessarily the best player. Mike Brearley wasn't the best batsmen but he could lift people. Steve Waugh's thinking about the game was unbelievable. He had a cricketing brain second to none. Never allowed a game to roll on. If the game wasn't going his way, he'd do something to change it. Alter the momentum on the field somehow.

A captain can't be static, whether that's on the field or during practice. You always have to be trying to make things happen. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn't.

Does a captain have to perform with bat or ball?

You still have to your bit, and for me that was with the bat. In my series as South African captain, Australia had a mystery spin bowler called Johnny Gleeson. When Australia played Transvaal and the other South African provinces, before the first Test, in Cape Town, whenever one of the Test batsmen came out to bat, Bill Lawry immediately took Gleeson off. Didn't want our batsmen to get a look at him. When it came to the first Test, none of us had faced Gleeson. He'd been to England the year before and we were told that he bowled mainly offspin there, but that's all we knew.

You still have to your bit, and for me that was with the bat. In my series as South African captain, Australia had a mystery spin bowler called Johnny Gleeson. When Australia played Transvaal and the other South African provinces, before the first Test, in Cape Town, whenever one of the Test batsmen came out to bat, Bill Lawry immediately took Gleeson off. Didn't want our batsmen to get a look at him. When it came to the first Test, none of us had faced Gleeson. He'd been to England the year before and we were told that he bowled mainly offspin there, but that's all we knew.

I was the first person to face him in the Tests, and I can tell you that for two overs, he made me look like a clown. As he ran up and bowled what I thought was an offbreak, I played for an offbreak, but it was a leg break. And vice versa. After two overs, I said to myself: you're making a fool of yourself here, there's only one way to deal with this. So I put my foot down the pitch and started hoicking him over midwicket. I got away with it, got 57. But I still didn't know which way Gleeson was spinning it.

Mike Gatting leads his rebel side onto the field for the tour opener in 1990. Ali Bacher says "the tour nearly destroyed me emotionally"•Getty Images

Are captains born or made?

Born. The ability to motivate people, to stay calm, lift and inspire players is in your genes. You can't be taught that if you don't have it.

Born. The ability to motivate people, to stay calm, lift and inspire players is in your genes. You can't be taught that if you don't have it.

When did you first captain a cricket team?

I started when I was in primary school. I was always captaining teams. Football, cricket, softball. The only team that I didn't captain was rugby. I was in the first team at King Edward [his school, in Johannesburg]. I was fly-half, I wasn't great. The cricket team, I always captained. I was captain of Balfour Park, a senior club team in Johannesburg, when I was 20, Transvaal when I was 21, and South Africa aged 28.

I started when I was in primary school. I was always captaining teams. Football, cricket, softball. The only team that I didn't captain was rugby. I was in the first team at King Edward [his school, in Johannesburg]. I was fly-half, I wasn't great. The cricket team, I always captained. I was captain of Balfour Park, a senior club team in Johannesburg, when I was 20, Transvaal when I was 21, and South Africa aged 28.

What was the first successful side you captained?

Yeoville Boys' Primary School's soccer team. In four years, we lost one match. We had such local support that on Wednesday afternoons, between one and two, when we played our games, the local shops closed so that people who worked in them could come and watch us play.

Yeoville Boys' Primary School's soccer team. In four years, we lost one match. We had such local support that on Wednesday afternoons, between one and two, when we played our games, the local shops closed so that people who worked in them could come and watch us play.

When did you get involved in cricket administration?

In the early 1970s, when I was captain of Transvaal, I was seconded to be an administrator on the board of Transvaal. I gave up playing cricket in 1974 to focus on my career as a doctor, but in 1981 I went into cricket administration professionally, again with Transvaal. I'd had ten years of involvement, part-time, working with some good administrators.

In the early 1970s, when I was captain of Transvaal, I was seconded to be an administrator on the board of Transvaal. I gave up playing cricket in 1974 to focus on my career as a doctor, but in 1981 I went into cricket administration professionally, again with Transvaal. I'd had ten years of involvement, part-time, working with some good administrators.

What is an administrator's job?

To make a good product that people want to watch. For that, your team needs to be winning and playing attractive cricket. Do that and the crowds will come in and you'll make good TV. Then your PR is good. It doesn't matter whether you're a marketing genius if you've got a good team. When I started, Transvaal under Clive Rice were a great team. That made my job much easier.

To make a good product that people want to watch. For that, your team needs to be winning and playing attractive cricket. Do that and the crowds will come in and you'll make good TV. Then your PR is good. It doesn't matter whether you're a marketing genius if you've got a good team. When I started, Transvaal under Clive Rice were a great team. That made my job much easier.

An administrator also has to come up with good ideas from time to time. We tried to introduce 14-man cricket, with three reserves, into 50-over matches. The captain could take someone off who wasn't doing well and replace them, like in football. Back then in South Africa, during the years of isolation, interest in cricket was dropping off. We didn't have international cricket, so we had to be innovative to keep people interested in the game.

Does a cricket administrator need to have played at the highest level?

When I was in ICC meetings there were some very good cricket administrators who had played at the highest level. Clyde Walcott, Doug Insole, Majid Khan. Their cricket knowledge was important, but an administrative board also needs good legal brains, PR, HR. You don't have to have played at the highest level of the game to make a contribution. Today, however, things have gone too far in the other direction. There is hardly a former player of note. Indian cricket has changed world cricket. Now it's all about money and TV rights.

When I was in ICC meetings there were some very good cricket administrators who had played at the highest level. Clyde Walcott, Doug Insole, Majid Khan. Their cricket knowledge was important, but an administrative board also needs good legal brains, PR, HR. You don't have to have played at the highest level of the game to make a contribution. Today, however, things have gone too far in the other direction. There is hardly a former player of note. Indian cricket has changed world cricket. Now it's all about money and TV rights.

What were your biggest challenges as a leader?

The Gatting [rebel] tour nearly destroyed me emotionally. The Hansie Cronje match-fixing scandal dug deep into my heart.

The Gatting [rebel] tour nearly destroyed me emotionally. The Hansie Cronje match-fixing scandal dug deep into my heart.

What are the most important characteristics for a cricket administrator?

Adaptability, flexibility, ruthlessness.

Adaptability, flexibility, ruthlessness.

What is your most cherished moment in cricket?

Helping to unify South African cricket administration into one United Cricket Board, after the fall of apartheid. The South African Cricket Board and the South African Cricket Union held their first meeting in September 1990. Nelson Mandela had just been released from jail. On one side was the SACB, blacks and coloureds, on the other the SACU, nine whites and one coloured. Steve Tshwete from the African National Congress' Sports Desk was the facilitator.

Helping to unify South African cricket administration into one United Cricket Board, after the fall of apartheid. The South African Cricket Board and the South African Cricket Union held their first meeting in September 1990. Nelson Mandela had just been released from jail. On one side was the SACB, blacks and coloureds, on the other the SACU, nine whites and one coloured. Steve Tshwete from the African National Congress' Sports Desk was the facilitator.

That inaugural meeting took two hours. And when Steve said, "Let's adjourn for lunch", the late Percy Sonn, who was with the SACB, got up and said: "Why have we been fighting each other?" The moral of the story is: talk to each other, get to know each other. That's the way to solve problems. That was the first ever meeting between the groups who ran white and black cricket in South Africa.

Setting up the United Cricket Board of South Africa wasn't easy. I played an important role, so I'm told. I was the CEO of the South African Cricket Union, which ran first-class cricket, and the late Krish Mackerdhuj was head of the South African Cricket Board, which represented black and coloured cricket. Steve Tshwete helped enormously.

He had been asked to bring together sports that had been divided by apartheid. I first met him in a township near East London in 1990, just after Mike Gatting's rebel tour, and we developed a fantastic relationship. Tshwete himself had been in prison on Robben Island for 15 years and thereafter in exile. During that first meeting, I spoke for 40 minutes and he never said a word, just looked at me. Then, when I stopped, he put out his hand and he said: "Ali, I'll help you."