How do bowlers adapt to different wickets?

There's plenty of discussion on what batsmen ought to do when encountering challenging pitches, but much less for bowlers

V Ramnarayan

11-Sep-2013

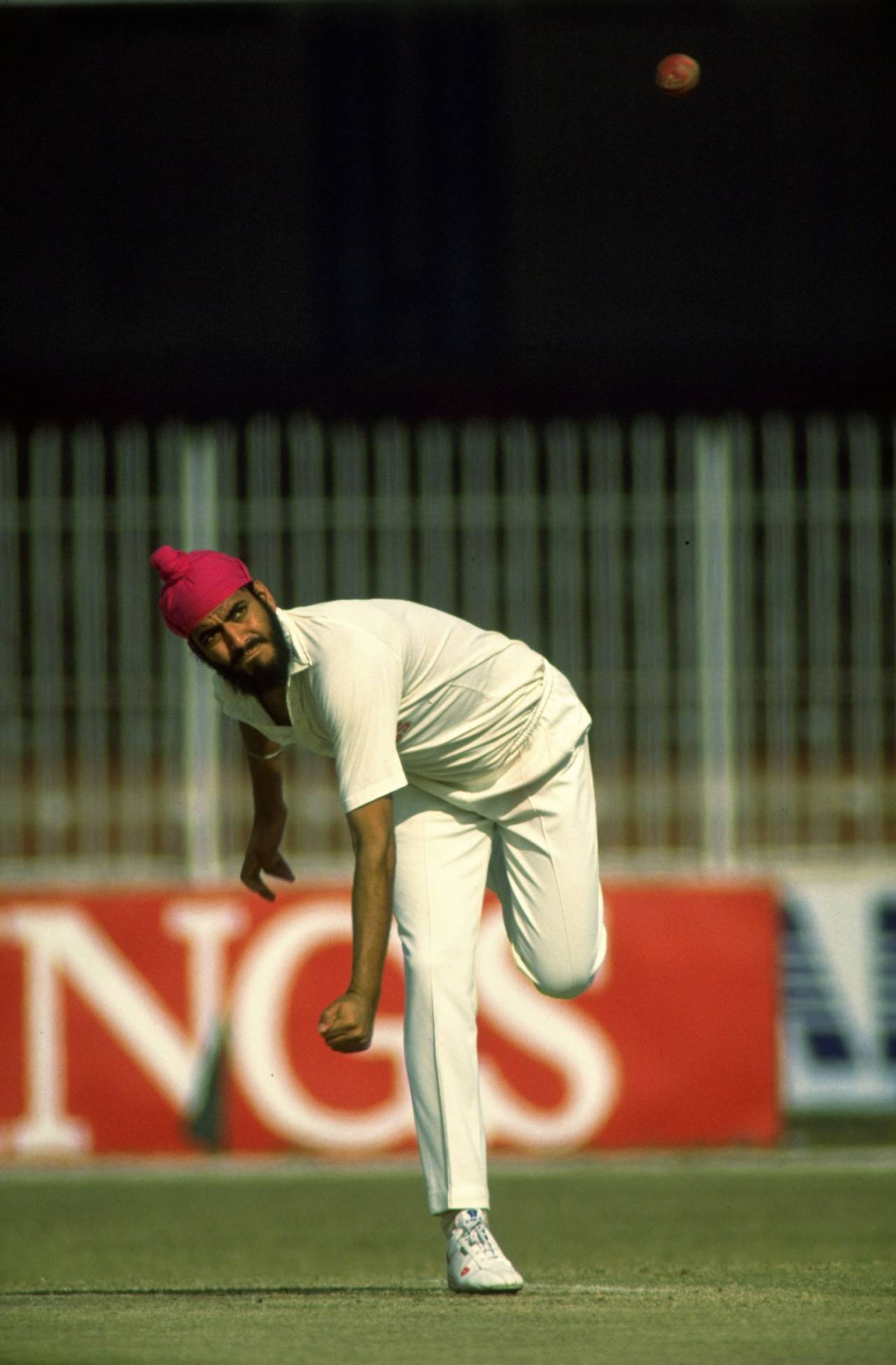

In the 1987 Bangalore Test, India's spinners struggled on a very helpful pitch because they didn't change their length and direction to make Pakistan's batsmen play often enough • Ben Radford/Getty Images

The broad-shouldered, weather-beaten man in his fifties was holding forth in the Indian Express sports editor's cabin, where I was summoned in my capacity as resident cricketer even if I was the baby of the editorial team.

"He murdered his wife," the visitor guffawed when the editor inquired after a certain princely contemporary of his. "She's an alcoholic," he declared with characteristic relish about a movie star.

He was Lala Amarnath, the larger-than-life allrounder and former India captain. In the city to coach the local Railways team, he had dropped in on his old friends at the Express.

The year was 1967. India had just made a disastrous tour of England, with few of their batsmen acquitting themselves well. In an interview to our sports correspondent, Lala predictably put the blame on our wickets, but not so predictable was the solution he offered. Though it applied less to English playing conditions than those India would soon encounter on their forthcoming tour of Australia, Lala's advice on how to prepare for Test cricket abroad was to play more domestic cricket on matting wickets. This would improve the Indian batsmen's back-foot play and their ability to cut, hook and pull with felicity and confidence.

I was nonplussed. I was sure Amarnath, with his vast experience and keen cricket brain, knew what he was talking about, but his views differed considerably from the prevailing local wisdom. We were constantly told that Tamil Nadu's matting-bred batsmen were found deficient in technique on turf wickets because of their tendency to play across the line and their lack of footwork against spin. I tended to agree with that school of thought, though I learnt over the years that exposure to matting wickets could help batsmen cope with pace and bounce, so long as they did not forsake the fundamentals of batting on turf.

I believe this ideal is best achieved if you learn your basics on turf and get to bat on matting in preparation for the bouncy tracks abroad, unlike batsmen of my generation, who cut their teeth on coir and found the transition to grass a challenge. Here again, the examples of Rahul Dravid and VVS Laxman are periodically trotted out, as players for whom being brought up on matting proved an advantage. This is something that needs to be examined closely before such a course is prescribed universally.

As if to prove that cricket is a batsman's game, there is hardly any writing or discussion on how a bowler can learn to adapt to different surfaces - such as matting, the pata wickets so common in India, slow turners, green tops, or vicious minefields.

Increasingly, with considerable investments being made in infrastructure across the country, young bowlers transit from matting to turf rather early in their careers, and probably adapt a lot quicker than we did in the 1960s, albeit, in the case of spinners, with undue haste to achieve accuracy rather than sharp ability.

The right line and length to bowl on slow or raging turners can pose quite a few questions to even experienced bowlers. A classic example was the Bangalore Test in 1987, when Pakistan's Iqbal Qasim and Tauseef Ahmed fared much better than Shivlal Yadav and Maninder Singh. The Indians did not make the batsmen play often enough, to do which they would have had to change their length and direction from their usual repertoire.

I remember my first experience on a drying pitch, during the era of uncovered wickets, in a league match in Calcutta, for Rajasthan Club under the captaincy of the inimitable Swaranjit Singh. The pitch was well-nigh unplayable but the batsmen hardly had to play me despite my alarming turn and bounce. For me, raised on Chennai's matting wickets, bowling on turf was a rare foray, even without the complication of the aftermath of rain. It never occurred to me to try to change the angle to force the batsman to play - by going round the wicket, for instance. As a result, an experienced pair of batsmen survived a torrid hour of batting to eventually build a sizeable partnership.

I am not familiar with the bowling drills at the National Cricket Academy, but I know that fast bowlers get to bowl on a variety of wickets at the MRF Pace Foundation. Where do the slow men learn the nuances of spin bowling in varying conditions? Barring a couple of exceptions - even at the international level - they tend not only not to "bowl in the right areas", but also to try so many variations within a single over that they rarely repeat deliveries that have the batsman in a spot of bother. Is there a case for fine-tuning the methods of coaching spinners to systematically facilitate their learning to bowl on a wide range of playing surfaces?

V Ramnarayan is an author, translator and teacher. He bowled offspin for Hyderabad and South Zone in the 1970s