Conrad Hunte

Michael Bracewell

Mark Chapman

Devon Conway

Jacob Duffy

Zak Foulkes

Matt Henry

Kyle Jamieson

Daryl Mitchell

Rachin Ravindra

Mitchell Santner

Alphabetically sorted top ten of players who have played the most matches across formats in the last 12 months

Full Name

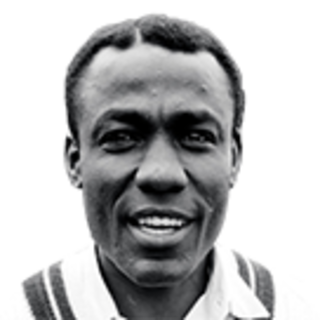

Conrad Cleophas Hunte

Born

May 09, 1932, Greenland Plantation, Shorey's Village, St Andrew, Barbados

Died

December 03, 1999, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, (aged 67y 208d)

Also Known As

Sir Conrad Hunte

Batting Style

Right hand Bat

Bowling Style

Right arm Medium

Playing Role

Opening Batter

Other

Administrator

TEAMS

Sir Conrad Cleophas Hunte died of a heart attack after playing tennis in Sydney on December 3, 1999, aged 67. Conrad Hunte was one of the greatest West Indian batsmen of a great generation; he also played a major role in the reconstruction of South African cricket, and was a figure of moral authority in the wider world. As a batsman, Hunte could match anyone stroke-for-stroke, especially on the leg side, if he wanted. But he subdued his attacking nature in Test cricket to let his team-mates play their shots, a decision which was vital in making the West Indian side of the early 1960s one of the most complete of all time. It was an early signal of the determined thoughtfulness that was to stamp his whole life.

Hunte was born in a one-room house on Barbados's Atlantic coast. His father worked on a sugar plantation, and Conrad was the oldest of nine children. He began playing cricket with the village boys at the age of six, using a palm-frond as a bat. His father was more anxious that he should get an education, and prevailed enough to ensure that his teenage son got work as a primary school teacher. But cricket slowly won the contest. Batting first in a representative match between two local leagues at Kensington Oval in 1950-51, Hunte was dropped on nought by Denis Atkinson, and went on to 137 not out. That secured him a place in the Barbados team when he was just 18, and he made 63 on debut against Trinidad. However, there was little first-class cricket in the Caribbean at that time, and his progress was frustratingly slow. He made 151 and 95 for Barbados in the important matches against E. W. Swanton's XI in 1955-56, and hoped that would get him selected for the 1957 tour of England. In the meantime he went to work at a bus plant and cotton mill in Lancashire, trying to get a chance in the Leagues. Out of sight, out of mind, he was omitted in 1957 - allegedly because he never replied to a letter - and spent that summer playing for Enfield.

He finally got his chance in front of his home crowd, when Pakistan toured the West Indies early the following year, and batted throughout his first day in Test cricket, making 142. Two Tests later at Kingston, Hunte made 260 - an innings overshadowed because his partner in a stand of 446 was Garry Sobers, who scored his record 365 not out - and followed that with a third century, a mere 114, in his fourth match, at Georgetown. Since Sobers made twin centuries, he was again second fiddle. Such form could not last, and he struggled in the subcontinent in 1958-59. My success had gone to my head, he admitted later. When the tour reached Pakistan, he was dropped. But, for all their strengths, West Indies were short of opening batsmen; indeed, throughout his Test career, Hunte never had a settled opening partner. Also, his class was not in doubt, and by Australia in 1960-61 he was a fixture, making the crucial throw in the Tied Test that stopped Wally Grout scoring the winning run, and then hitting 110 at Melbourne.

The cricket on that tour, however, was secondary to the real change in his life. The captain, Frank Worrell, encouraged the players to build good relations locally, and Hunte impressed many people with the eloquence of his speeches. A local journalist, James Coulter, took him to see a film called The Crowning Experience, based on the life of the black American teacher Mary McLeod Bethune. This was promoted by Moral Re-Armament, the then-vogueish organisation which strives to provide an ethical basis for society. In England, on the way back home, he went to see Dickie Dodds, the former Essex batsman and dedicated MRA man. Hunte was taken to a conference in Switzerland, and resolved to pay back £10 he had cheated on his tour expenses three years earlier, and to live his life by new standards: absolute honesty, absolute purity, absolute unselfishness, absolute love. Henceforth, between cricket commitments, he travelled on behalf of MRA.

Hunte came to England in 1963 as Frank Worrell's vice-captain, and he took the decision, with the same certainty that he declared for MRA, to curb his attacking instincts and become the team's sheet-anchor. He began the series at Old Trafford with one match-winning innings, 182, and finished it at The Oval with another, 108 not out. When Worrell retired, Hunte hoped for and expected the captaincy. Sobers was appointed instead; there was speculation that Hunte's heart-on-sleeve nature and his continuous proselytising for his beliefs even within the dressing-room told against him. He wrestled with his bitterness and his conscience for six weeks before waking up a rather bemused Sobers in his hotel room to proclaim that he would keep playing, and do his utmost. He did: though he failed to make a century in the next series, home to Australia in 1964-65, Hunte topped the Test averages with 550 runs at 61.11. He made another Old Trafford hundred at the start of the 1966 series, and his eighth and last Test century in Bombay that December, batting with the debutant Clive Lloyd. His final Test average, just above 45 in 44 Tests, was a mark of his quality.

Some sources give Hunte the credit for persuading his team-mates to stick with the tour in India after a riot in Calcutta, though it is uncertain how much the team listened to him by then. He was in the habit of leaving notes around the dressing-room containing uplifting messages: It was tiresome for some of the boys, said Sobers. Even Hunte's mentor Dickie Dodds admits there might have been a problem: They certainly pulled his leg. But I think he was the conscience of the team, and his moral force gave the whole side an ethos. After retiring from cricket, Hunte worked for better race relations through an MRA inter-racial group, and travelled the world before settling in Atlanta, where his wife Patricia was a TV newsreader. In 1991, as South Africa inched towards change, he rang Ali Bacher and pleaded to be allowed to help the reconciliation process. He kept phoning, then arrived and stayed for seven years, quietly funded by MCC, with the title National Development Coach. The emphasis was on motivating and inspiring young people in the townships. He was a magnificent influence. However, shortly before he died, Hunte had returned to Barbados, with encouragement from the Government, which knighted him in 1998. There he won a fiercely contested election to became President of the Barbados Cricket Association, with a mandate to revive it. There was talk of him standing for the presidency of the West Indies Cricket Board. Amid all this, he remained deeply committed to the cause of his life, and was due to speak at an Australian MRA conference when he died. I've never met a better person, said Bacher, who worked with him all through the South African years. I never heard him speak ill of anyone.

Wisden Cricketers' Almanack

West Indies cricket sustained another disabling blow with the sudden death of Sir Conrad Hunte on December 3, aged 67. He succumbed to a heart attack while playing tennis with friends in Sydney, Australia, where he had gone as keynote speaker at a conference of Moral Re-Armament (MRA) to which he had committed his life since 1961 when: during West Indies' tour of Australia, he saw a film on the Christian-based movement in Melbourne. In desperate need of strong, visionary leadership from the committed and respected greats of the past, the game in the Caribbean lost two men capable of providing it in the space of a month. One Saturday afternoon, Hunte was acting as one of the pallbearers at Malcolm Marshall's funeral; three weeks later, he himself had passed on.

Less than two months earlier, Sir Conrad had been elected president of the Barbados Cricket Association (BCA), a prelude to what surely would have been evenwider involvement in the game. Hunte was the consummate, and only stable, opener of the powerful West Indies team of the 1960s, quick of eye, nimble of footwork and precise in judgement of length and line. Even without the benefit of a consistent partner he accumulated 3,245 runs at an average of 45.06 in his 44 Tests. Hunte took 13 different batsmen to start the innings with him during the 10 years of his Test career, skilfully compromising his attacking instincts to be an effective and essential counter to the flamboyant stroke-makers who followed him, like Garry Sobers, Rohan Kanhai and Seymour Nurse. His success could be measured as much by the fact that his eight hundreds were spread around four continents against every opponent he came up against as by his impressive statistics. Even they do not attest to his additional asset as a fast, sure-handed cover fielder with a powerful, flat throw that famously ran out Wally Grout from deep midwicket as he scrambled for the third run that would have won Australia the tied Test in 1960.

As West Indies vice-captain for eight years, Hunte was a loyal lieutenant, first to Frank Worrell, for whom he held a hallowed regard, then, on Worrell's retirement, to Sobers. He admitted subsequently that he was so gravely hurt to have been passed over for the leadership in favour of Sobers, reportedly on Worrell's advice, that he considered quitting. True to his Christian values, he soon dismissed his disappointment and remained a stabilising influence to the tactically more impetuous new captain.

Hunte came late to Test cricket. Like so many West Indian cricketers, he was born into a large, poor family, the eldest of nine children whose father worked on a sugar plantation in St Andrew on the rugged east coast of Barbados. Also like so many before him, his talent was nurtured through the Barbados Cricket League (BCL), the efficiently administered competition for the island's neglected country areas. By the time he gained his first Test cap in 1958, aged 26, he had already played for Barbados for eight years and was widely regarded as the best opener

His impact was immediate. He took 142 off Pakistan in his debut innings, on his home ground of Kensington Oval, Barbados, and almost doubled that in the Third Test of the series with 260, the significance of which was overshadowed by an even more monumental innings by his partner in a record second-wicket partnership. After Hunte was run out to end the stand at 446, Sobers went on to his unbeaten 365, surpassing Len Hutton's mark as Test cricket's highest Test score.

Athletically trim to the end and, in his heyday, physically fit, he was nowhere near past his best when he chose to give up the game and devote his life to MRA in 1968. Quick-witted fans immediately gave a new interpretation to MRA-'More Runs Available'. He transferred from London in the late 1970s and lived for 12 years in Atlanta, USA, where, in addition to his MRA mission, he worked in independent financial services and was Barbados' Honorary Consul. It was there he met and married Patricia, an American who was a noted television personality. The couple had three daughters.

Cricket blood, however, coursed through his veins and, as the walls of apartheid began to crumble with the release of Nelson Mandela from Robben Island and cricket administration in South Africa came under a united board, Hunte recognised a new and urgent mission. He called the chief executive officer, Dr Ali Bacher, in Johannesburg and offered his services. Accepted, he spent seven years there, concentrating on developing the previously disregarded talent in the black townships and, under the sponsorship of an MCC programme, touring the rest of Africa, spreading the gospel of cricket and, inevitably, of Jesus Christ. He was even made manager of the South Africa women's team to England in 1997.

But his homeland eventually needed him too. His services to cricket were recognised in 1998 when he was awarded Barbados' highest honour, the Order of St Andrew, yet the game that had been an all-embracing way of life a to his countrymen was losing its place in the psyche of the youth. Concerned about the decline, Prime Minister Owen Arthur sought out Hunte in South Africa and encouraged him to return to apply his experience and expertise in helping to revive interest and standards. He was attached to the Ministry of Education and Youth Affairs and became immersed in his task.

It was no surprise that he could be persuaded to seek the presidency of the BCA nor that he was duly elected. He was full of ideas and energy. He could see clearly where Barbados and West Indies cricket should be heading, and how it should get there, as the 21st century dawned. Ironically, it may have been all too much for a heart that a doctor in South Africa had alreadydetected was in need of a rest.

Ever generous with his advice and cheerful in his outlook, he leaves memories of a happy cricketer and an enlightened man of the world whose love of the game, and of his country, was surpassed only by his love of God.

The Cricketer

Conrad Hunte Career Stats

Records of Conrad Hunte

Explore Statsguru Analysis

Recent Matches of Conrad Hunte

| Match | Bat | Bowl | Date | Ground | Format |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROW XI vs Pakistan | 0 | 2/37 | 12-Sep-1967 | Lord's | OTHEROD |

| ROW XI vs England XI | 37 | -- | 09-Sep-1967 | Lord's | OTHEROD |

| West Indies vs India | 49 & 26 | 1/25 | 13-Jan-1967 | Chennai | Test # 614 |

| West Indies vs India | 43 | 0/5 | 31-Dec-1966 | Eden Gardens | Test # 612 |

| West Indies vs India | 101 & 40 | -- | 13-Dec-1966 | Brabourne | Test # 610 |

Debut/Last Matches of Conrad Hunte

Test Matches

FC Matches

List A Matches