Why bring up match-fixing now?

It's been 10 years since the Cronje scandal, but despite preventive measures the threat is very much alive

Why should 2010 be treated as a landmark of any significance in cricket's match-fixing years? The boom years, after all, were over a decade ago, the mid-to-late 90s, when Mukesh Gupta, "John"s and many others led the cricket world in a finely orchestrated but unholy dance of money and greed. And the practice probably began much before that. So why now?

For a number of reasons this year is important. A full decade ago now, cricket first began to fight back. Three big names, captains or former captains, were banned for life in 2000, as a result of various investigations and commissions and inquiries. The ICC set up the anti-corruption unit (ACSU) the same year, the first systemic, if greatly delayed, response to the issue. So the year is important, first, in assessing where cricket stands now.

Lord Paul Condon, who set up and oversaw the ACSU through the decade, has just left his post, and that is a natural marker. He believes the game is in a healthier state than when he took over, though he acknowledges that new formats and leagues bring greater threats. In that there is now a body in place to investigate and to apply preventive and punitive measures, there has been progress. Players minded to do so can take an official route to report suspicions. And there has been no rash of high-profile cases as there once was. By and large the game appears clean, or cleaner than before.

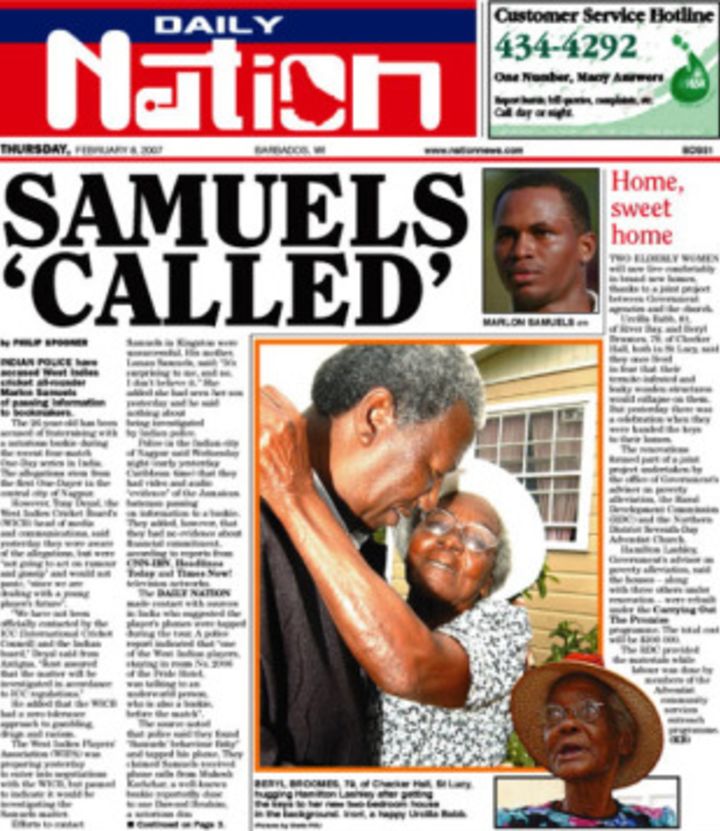

But setting up a police force doesn't vanquish crime. If you actually scan the last 10 years and put together in one paragraph cricket's main run-ins with match-fixing and bookies, is there not still danger? Off hand, just tally them up: Maurice Odumbe's tryst with bookies and subsequent ban in 2004; the panic over Murali's visit to a dance bar in Mumbai, whose owner was said to have bookmaker contacts; Marlon Samuels and the tapped Indian phone line in 2007; the persistent murmurs about the ICL in its last season; the approach to an Australian player during the Ashes last year; separate offers made to players during the 2009 World Twenty20; the ongoing investigations into the actions of Danish Kaneria and Mervyn Westfield of Essex; the recent development that county cricket might now be attracting more bookies than old men or dogs; Shakib Al Hasan's recent revelation that he too was once tapped up.

And this leaves out Pakistan's paranoid world, where every match is fixed. But even among that long, crazed list, some genuinely provide reasons for concern. Who did three Pakistanis meet at a function during the 2007-08 India tour, a meeting that prompted the ACSU to interview the players a few months later? And how suspicious were the men who compelled the team to change floors in a Colombo hotel in 2009? All together, the list is of some heft. And it says that bookies never really went away or stopped trying; they merely aren't as audacious as they were in Gupta's days. And looking over the Samuels case for example, it remains absurdly straightforward for a bookie to contact a player.

Not only are they still around, but it is only over the last decade that our understanding of just how broad their work is has properly developed. At the time the simple and prevalent belief was that match-fixing involved fixing results. In many cases it was true. It was also convenient, for it left open the romantic, blind notion that one guy, incensed by this corruption, could change the tide. Lance Klusener, for example, is said to have deliberately screwed up a good deal for Hansie Cronje in the Nagpur ODI on the 1999-2000 tour by smashing a late, innings-changing 58-ball 75. There was also the neat chestnut with which we comforted ourselves that all bets on India were off until Tendulkar was out.

Cynical the scenario may be, but even a reasonably intelligent bookie might think it worth his while to approach players from cricket's third world, who also miss out on the lucre of the IPL

Now we know it doesn't matter what Tendulkar does, for the reality, as the ACSU's first comprehensive report revealed in 2001, was far more complex. They called it occurrence-fixing, but soon Rashid Latif would give it a far more evocative name: fancy-fixing, which opens up cricket's vast statistical landscape. With fancy - or spot - fixing, each ball of a match is effectively an event, an opportunity to bet and thus an opportunity to fix. It emerged that bets were being taken on the outcome of the toss, the number of wides or no-balls in a specific over, the timing and specifics of declarations, individual batsmen getting themselves out under a specific score, even field settings.

A visit last year in Karachi to an individual familiar with the world of bookies was mind-altering: bets were placed on what the first-innings total in a county match would be by lunch on the first day, or how many overs a bowler would bowl in the first hour of a session or a day, or on how much difference there would be in first-innings totals, or on how many runs a specified group of players would make. It didn't stop.

In a way, fixing entire results was just the very furthest reach of bookies, the most sensational thing they could do; everything beneath that, initially overlooked, was much more doable, less easier to spot and thus more dangerous. The thirst for fixing results, even if diminished, remains, as one English county player approached by an Indian businessman recently learnt, but the far greater problem and more prevalent is fancy-fixing.

Moreover conditions today are such that you can't help but worry. The 2001 ACSU report listed key factors at the time that led to the entire pickle. Cricketers weren't paid enough money compared to other professional sportsmen; without contracts their careers were less stable; too many ODIs where nothing was at stake were being played; cricketers had little say in the running of the game. Cricket thinks it has moved on from then, but not as much as it thinks it has.

Central contracts are now in place across the board, giving the elite international cricketer some security. Players are generally better rewarded financially than they have ever been. Indeed, some of the amounts cricketers received at the time from bookies seem laughable now: $4000 here, $5000 there. The big fish often took around $50,000 for a really big fix; Saleem Malik was said to have offered Mark Waugh, Shane Warne and Tim May nearly $70,000 each during the 1994-95 Karachi Test. Cronje once even agreed on $15,000 for a fix. In the 2009 IPL, Andrew Flintoff's two wickets in four Twenty20 games fetched him over $166,000 each, legally and above board.

But the riches are limited and wealth is spread more unevenly than ever before; players from India, Australia, England and South Africa enjoy far greater financial benefits than ones anywhere else. The IPL has taken the earnings of some players to a different level altogether, but it has also widened the gap between haves and have-nots. Cynical the scenario may be, but even a reasonably intelligent bookie might think it worth his while to approach players from cricket's third world, who also miss out on the lucre of the IPL. Maybe it explains why county players have been targeted, or Bangladesh's Shakib was recently, or why Pakistan's players might be approached.

Above all, in 2010 there are more games, and more meaningless ones, than ever before. When Cronje discussed with his team an offer to throw Mohinder Amarnath's benefit in December 1996, it was prompted in part because none of his tired team was keen to play a match that had only hurriedly been given international status. Since then it has only gotten worse. There is an entire new format to deal with, for one. The seven-match ODI series, pregnant with the possibility of ennui and dead games, is not only still around, there are more of them. Before 2000, there had been eight (one was an eight-match series). Since then there have been 10. Every week, the BCCI and Sri Lanka Cricket seem to thrust upon a weary world another tri-series. The push to provide greater context and meaning to ODIs should have begun in 2000. Instead, the ICC has dithered for a decade, only beginning to take it seriously now.

And it is all on TV. All matches, from English county cricket to the Australian Big Bash, from the South African MTN40 to Pakistan's RBS Twenty20, from the Under-19 World Cup to the women's World Cup, can be beamed into your home, mine, or that of the bookie. Every international game, and an increasing number of domestic games, are potentially a target.

So in 2010 the threat is very much alive. Over the coming weeks, Cricinfo will bring you a series of special features on the topic. There will be an interview with Lord Condon as he steps down from his post. We examine the effects match-fixing has had on Pakistan, since arguably the country is the one most scarred by the events. We also look back, through journalist Malcolm Conn, at the breaking of the Mark Waugh-Shane Warne story that Cricket Australia had hushed up for so many years. And at the after-effects of the Cronje revelations in South Africa. There will be much else besides.

Osman Samiuddin is Pakistan editor of Cricinfo

Read in App

Elevate your reading experience on ESPNcricinfo App.