Cricket nuts are people too

This book offers the story of England's much misunderstood band of travelling supporters from the inside

R-E-S-P-E-C-T. That's all the Barmy Army crave. That they still have their detractors is almost certainly because they're such an easy target for the primarily middle-class English media, and it all starts, of course, with that self-mocking name. Barmy, after all, is another take on "loony", "bonkers", "potty" and sundry other deliciously wry English words denoting a lack of mental mettle. Happily, as journalist Winslow affirms in his wry, perceptive and winningly written travelogue of life on the road "chasing the cricket dragon", the brand of looniness favoured by foot soldiers such as himself is not only almost entirely benign (Ricky Ponting doubtless disagrees) but, in its way, rather beautiful. In a sweet, sweaty, bromantic sort of way.

Rewind to North Sound, Antigua, February 2009. The briefest Test match yet is over, done and dusted in ten balls. "The bowlers were having trouble with their footings," explained Alan Hurst, the match referee. "We considered it very dangerous." So uncannily did the outfield resemble a beach, it was a shock to discover that water wasn't lapping the boundary edge and the spectators weren't aboard their pedalos.

At 3pm, remarkably, came an announcement: another Test would start at St John's two days later. The driving force behind this rare instance of on-the-hoof administration was Giles Clarke, chairman of the England and Wales Cricket Board, who'd made his fortune trying to satisfy his customers, in particular their desire for affordable plonk. This time, he'd been listening to an angry crowd. As was now the norm, thousands of British tourists were spending their vacations following the England team to far-flung former territories. On tours of the Caribbean, moreover, it was now almost habitual for holidaymakers to outnumber locals, often considerably so.

But for the presence and remonstrations of the Barmy Army, it is extremely doubtful that such swift action would have been countenanced, much less taken. Yet until fairly recently, among the English media, the consensus was both unequivocal and unshiftable: not only was the average Barmie rude, crass and never knowingly sober, he (and they were always "he") possessed a few thousand cells too few for an operable brain, not to mention having far too much in common with his f***ball-besotted counterpart.

Indeed, that provocative maestro of the look-at-me tirade, Matthew Norman, actually had the brass balls to claim in the Daily Telegraph that, unlike the Barmy Army - "that coalition of saddoes… the only faction of any sporting audience in history whose primary motivation for attending games is not to watch but be watched" - football thugs "had integrity", a statement Winslow neatly and thoroughly demolishes for its intergalactic remoteness from fact. The image, nonetheless, was set in stone and ink: a bloody national disgrace.

This has always struck me as profoundly snobbish, not to say grotesquely unjust. After all, what national team, in any sport, can command such a devoted caravanserai, such a loyal source of lung power and lusty encouragement? Even now, the most damaging and regrettable incident involving an England cricket fan dates back to Perth 1982, a dozen years before the first Barmy Army t-shirt went on sale, when Terry Alderman dislocated a shoulder bringing down a pitch invader. Consider, too, those allegations of self-aggrandisement. A recent browse through the Army's website forum revealed 1685 posts for "Barmy Army Chat" and 19,408, more than ten times as many, for "General Cricket Chat".

The main difficulty, attests Winslow, lies with perceptions and, in particular, the Army's "schizophrenic identity issues". "Those who have been involved in shaping it, maintaining it, developing it and caring for it have a clear definition of what it is, but those who write about it, those who join it without realising what it stands for, and even those who are not involved at all can both skew public opinion and have a damaging effect on its reputation." Yet even that definition - cricket-loving patriots - falls short: sure, there's the hardcore group that flew steadfastly to India after the 2008 Mumbai atrocity but then there are those who turn up for a couple of Tests in the more attractive cities. "Even to us the Army can be a different beast every day, and some days we like it more than others."

It is impossible to quantify how much Andrew Strauss' team benefited from Bill Cooper's uplifting trumpet or those endless renditions of "Everywhere We Go" and "Jerusalem" on their triumphant Ashes tour of 2010-11 (by when Norman was virtually alone in his condemnation), but why not settle for the view propounded by Graeme Swann in his foreword to this entertaining volume: "They are not hooligans, they are not troublemakers, they are just cricket nuts who fly the flag for this brilliant country we live in. They are the very heartbeat of our Test team abroad. And I love them for it."

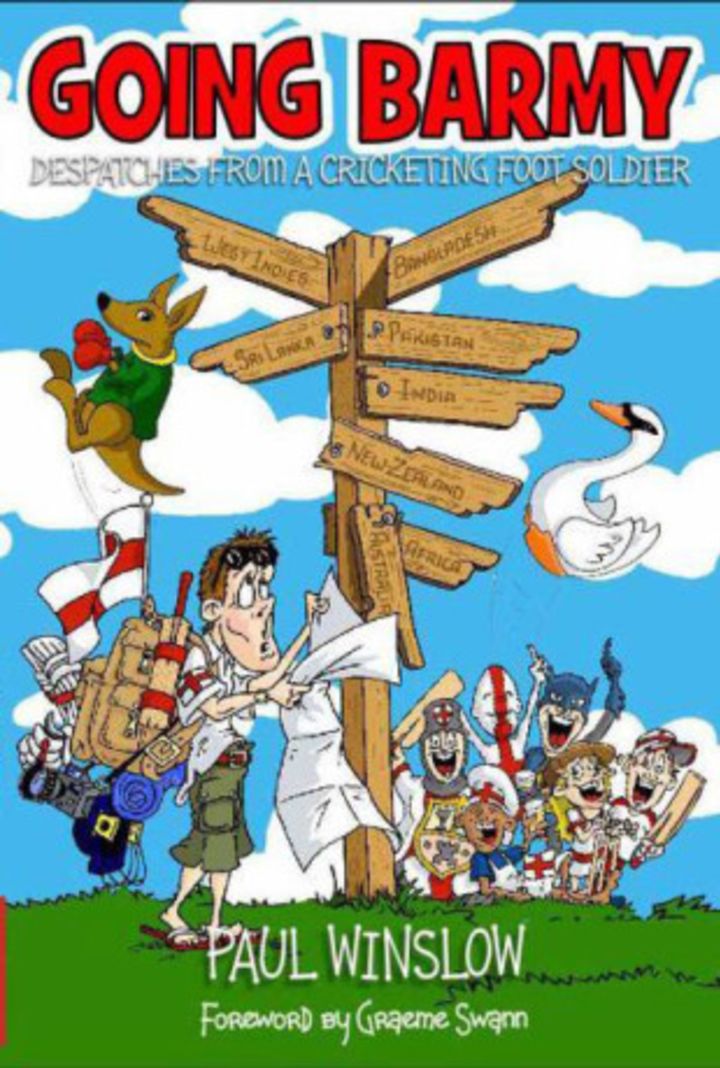

Going Barmy: Despatches From a Cricketing Foot Soldier

by Paul Winslow

SportsBooks

£8.99, pp 310

Rob Steen is a sportswriter and senior lecturer in sports journalism at the University of Brighton

Read in App

Elevate your reading experience on ESPNcricinfo App.