Playing with Barry

Andrew Murtagh's book about his legendary Hampshire team-mate is packed full of anecdotes, detail and research

Written by one of Barry Richards' former fellow professionals at Hampshire CC, this is a remarkable book. It is unique, first of all, for its generosity and warm-heartedness. What intrigues, secondly, is the fact that it is neither penned by the subject himself nor by a ghostwriter, journalist or writer. As a result it has a slightly strange perspective in relation to its subject matter, neither one of safe distance nor compromised proximity.

Andrew Murtagh doesn't stand to Richards as, say, David Walsh stands to Kevin Pietersen. Rather, he played alongside Richards, marvelled at his lazy audacity while on - fairly regular - 12th man duty at Hampshire, and generally occupied the same professional environment for several years. The book, then, is a paean, almost, to talent lost. For Murtagh, one of the motivations for writing seems to be to shore up the memory of Richards from history's neglect. We are reminded of EP Thompson, the English left-wing historian, who once spoke of rescuing the croppers and artisans of the English working class from the "enormous condescension of posterity". Murtagh's project aims for much the same thing.

Richards, we read, was an only child in a not entirely happy household. His father was professionally thwarted - and distant - his mother and grandfather kinder, more supportive. The family weren't rich but they were nonetheless privileged in that contradictory way that characterised much of white South Africa in the 1950s and '60s. So, for example, Richards, slept on the stoep (the verandah) because the flat in which the family lived was too small to accommodate him elsewhere. Yet he was waited upon and grew up being domestically lazy. Murtagh tells a couple of good yarns about Richards' digs in the early Hampshire days. Let's just say that, as a cook, Barry wasn't Jamie Oliver.

Richards compensated for his loneliness while growing up by playing cricket and eyeing bikini-clad beauties round the local swimming pool. Enrolment at Treverton, a boarding school in the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands, was short-lived because he was homesick and, increasingly, lived only for cricket. Although there was the odd time when he treaded water, the passage upwards was irresistible. He went to England with a powerful SA Schools Side in 1962, and although he took frustratingly longer to make his provincial and Test debut, from his middle teens this seemed almost inevitable.

Of the schoolboy tour Murtagh tells a lovely anecdote about the wide-eyed youngsters bumping into Muhammad Ali while walking around Piccadilly. When he found out where they were from, Ali wasn't best pleased; naïve, protected colonials, they were confused at why they should inspire such Louisville Lip. It was something Richards was to encounter more of as the decade progressed.

Like Gordon Greenidge, his one-time opening partner at Hampshire, Richards played county cricket before he played for his country. Richards didn't have the best of starts, but plumped for Hampshire rather than Sussex because they paid more. Inevitably his county debut was against Sussex in Hove. John Snow was bowling quick, the pitch had a splash of green and it was still May cold. Richards had allowed himself to be quoted beforehand to the effect that he would score 2000 runs in the season, though he argued later that he'd been misquoted. Batting at four, he promptly found himself walking in at 15 for 2. It was soon 15 for 3; Mike Buss was overheard to say as the two passed: "Only 2000 more to go, then, Barry."

Richards' county innings became the stuff of legend - a John Player knock against Bishan Bedi of Northants, one against a Yorkshire attack in all its pomp in Scarborough, a casually strutting 170-odd in April at Lord's - but he became easily disheartened. Indeed, he was the prototypical slacker, often needing external motivation to stir his juices. Sometimes it was competition with Greenidge, or tourists, or the fact that there were cameras at the ground.

With ennui loitering, Richards' destructiveness had an unmistakable tint of solemnity. Watching footage of his 325 in a day for South Australia against Western Australia just after the end of his four-Test career, shows a player whose contempt seems without bounds and pleasure. Such was the melancholy of his generation.

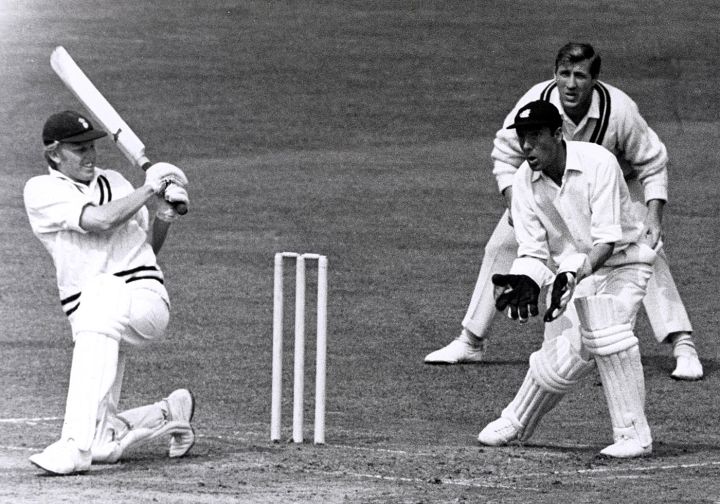

For all the accuracy of Murtagh's story, all the painstaking accumulation of detail and research, Richards the man is a pale shadow of his deeds. We never really get to know him. We read of a certain reserve, the ease with which he was bored, his aptitude for a deal, his love of squash and golf. He was restless, he drove a Ford Capri (number plate BAR 777J) when he first arrived at Hampshire, and seemed to gravitate towards extroverts. At the crease, with feet close together, hands high on the handle, he looked almost frail. The impression didn't last for very long.

Sundial in the Shade - The Story of Barry Richards: the Genius Lost to Test Cricket

By Andrew Murtagh

Pitch Publishing

256 pages, £18.99

Luke Alfred is a journalist based in Johannesburg

Read in App

Elevate your reading experience on ESPNcricinfo App.