The birth of the World Cup

The low-key launch of the tournament in 1975

Martin Williamson

31-Jan-2015

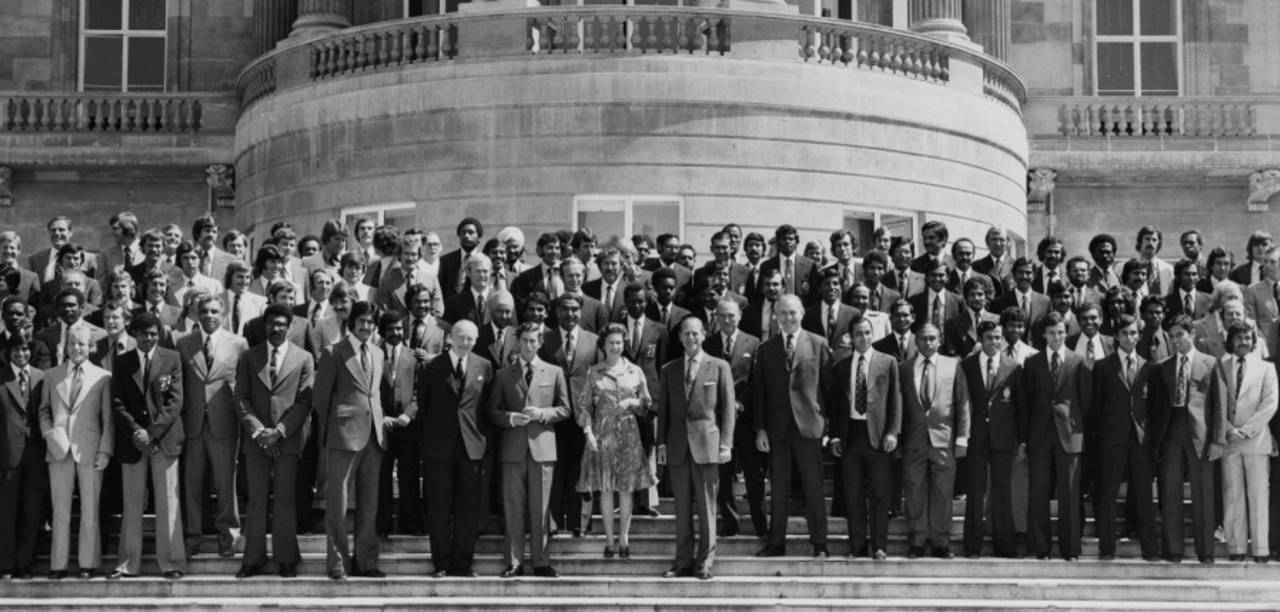

The squads are entertained at Buckingham Palace on the eve of the tournament • Getty Images

It is easy to think that the ICC Cricket World Cup has always been a bloated and rather self-indulgent affair, lasting as long as football's World Cup and the Olympics combined and with as much emphasis on making money as on the game itself. But the inaugural tournament in 1975 was a quaintly gentle affair, squeezed almost apologetically into a fortnight in early June.

In the modern era the hype around the World Cup begins months, if not years, before the tournament itself. Forty years ago it started almost unnoticed by the general public, and was viewed with slight puzzlement by the players. Javed Miandad, aged 17 and uncapped, told ESPNcricinfo last year there was little fuss over his selection for Pakistan. "We didn't know what the World Cup itself was. Actually, I think none of the teams knew what to make of it."

A myth has grown up that the ICC decided to run a World Cup on the back of the inaugural women's tournament in 1973. Although it rubber-stamped the plan three days before the women's final, the idea was first raised at its annual meeting a year earlier and a committee to look into the viability of such an event was set up. The details were vague, with John Woodcock in the Times stating that "it may even be the whole summer will have to be set aside to fit it in".

One major barrier was overcome at that meeting when the heads of the Pakistan and India boards informally discussed resuming cricketing relations, which had been suspended after the 1965 war over Kashmir. Had they stood firm and refused to co-operate then the World Cup would have been almost impossible, given there were only four other Test-playing countries at the time. The other obstacle - South Africa, at the time two years into isolation - remained a thorn in cricket's side for almost two more decades.

The green light was given by the ICC on July 25, 1973, although it baulked at calling the tournament "World Cup" for fear that would give the one-day game - still in its infancy and regarded with suspicion by many - "too great a significance". Instead, it preferred what Crawford White in the Daily Express called "the insipid" "International Tournament", a title almost nobody used. The next day's papers settled on "World Cup" and that was that. To make up the numbers, Sri Lanka and an East Africa side (drawn from Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and Zambia) were invited to join the party.

The Test & County Cricket Board (the forerunner of the ECB) had been the driving force and the ICC left it to handle almost everything, so the competition was played under Gillette Cup (60-over) regulations. Money was a worry. The TCCB estimated the cost of the tournament would be around £100,000, and the board's unease was not helped by the large financial hole left by the women's tournament, which had only gone ahead as it had been bankrolled by millionaire Jack Hayward, who had paid £40,000 towards the costs.

The competition was scheduled for the second and third weeks of June 1975, the gap in the fixture list coming about because that summer had been earmarked for a tour by South Africa. That visit was scrapped in September 1973, allowing the TCCB to immediately invite Australia back for a lucrative extra Ashes series immediately after the World Cup, thereby ensuring that even if it lost money on the new venture it would not be out of pocket.

The draw, such as it was, was announced a year in advance and was done with certain restrictions. England had to be apart from Australia (which they would not have minded one bit after a 4-1 Ashes drubbing the previous winter), Sri Lanka (who the British press insisted on referring to as Ceylon) from East Africa and India from Pakistan.

As it turned out, by the autumn of 1974 the ICC and TCCB, who had agreed to share income, were predicting TV rights and sponsorship could generate as much as £750,000, though a sponsor had not been found.

In October that gap was filled when a deal with Prudential Assurance, which had sponsored the short international one-day series in England since it began in 1972, was announced. The £100,000 Prudential put in covered all costs, meaning gate receipts, and broadcast revenue was all profit. The ICC asked everyone henceforth to refer to the tournament as the Prudential Cup. It continued to be the World Cup in the minds of the public and most of the media.

The teams arrived in England in the fortnight before the opening game on June 7 to acclimatise. Plans were undone by weather so poor that only five days before the curtain raiser a County Championship game was snowed off. East Africa were left in no doubt as to the measure of the task facing them when they went down to Somerset by 163 runs, while other countries had their preparations disrupted by the Benson & Hedges Cup quarter-finals, with county-contracted players called back to play three days before the start of the World Cup.

On the eve of the start the teams were entertained by the Queen, Prince Phillip (who as president of MCC presented the trophy to Clive Lloyd 15 days later) and Prince Charles at Buckingham Palace. "She's just great," Jeff Thomson grinned afterwards, although he was less happy 24 hours later after being no-balled 12 times for overstepping.

The pre-tournament marketing campaign was low-key even by the standards of the time. This was about the extent of it, complete with borrowed Disney characters•Martin Williamson

The media did not really take much notice until the morning the tournament started, and even then coverage took second place to Wimbledon tennis champion Jimmy Connors' unexpected defeat at Chichester. Woodcock predicted "it promises to provide some of the greatest excitement and most brilliant cricket of the season" but also warned that "the game must keep pace with the times without letting the times run away with the game". Tony Lewis was less enthused. "Cricketers from seven countries flown into England… to smite seven shades of hell out of each others' bowling… too much of a circus act."

The opening day was blessed with glorious sunshine and good crowds. England routed India in front of almost 20,000 at Lord's in one of the most bizarre World Cup games of all time, Sunil Gavaskar batting 60 overs for 36 not out as India managed 136 for 3 chasing 335. At least the other televised match kept a full house of 21,000 at Leeds entertained as Australia beat Pakistan. At Edgbaston, Glenn Turner filled his boots, making 171 not out as New Zealand thrashed East Africa by 181 runs, and at Old Trafford pre-tournament favourites West Indies skittled Sri Lanka for 86, the crowd greeting news that the minnows had been put in by Lloyd with audible groans.

It had not been a perfect start but it had grabbed the public's attention. Ticket sales for the second round of matches, which had been poor, picked up. Edgbaston had only sold around 1000 seats for Pakistan v West Indies but on the day, around 20,000 crammed into the ground for what turned out to be an outstanding game. A classic final was the icing on the cake, and the cash rolled in. The World Cup was here to stay.

What happened next

Is there an incident from the past you would like to know more about? Email us with your comments and suggestions.

Bibliography

A Summer of Cricket Tony Lewis (Pelham Books, 1976)

A Summer of Cricket Tony Lewis (Pelham Books, 1976)

Martin Williamson is a former executive editor of ESPNcricinfo