Traicos trumps Tendulkar

When Andy Zaltzman realised Sachin was destined for greatness (though he will never surpass a certain Zimbabwe offspinner)

All cricket fans cherish moments when they first see a player, and think to themselves: “This lad is something extraordinary.” They cherish them even more when they turn out to be correct. Few would boast that when they saw Paras Mhambrey bowl for the first time, they just knew deep down that he would go on to take 400 Test wickets; or that they happened to catch a glimpse of Blair Hartland’s debut Test innings whilst on holiday in New Zealand in 1992, and instantly wrote a series of postcards home telling their parents that Wally Hammond himself had been reborn as a Kiwi opener.

Many will have thought it during Cheteshwar Pujara’s mesmeric, match-sealing fourth-innings 72 on debut in Bangalore, for his timing, his decisiveness and precision of shot, and his ethereal stillness at the crease. Time will tell. Time is often a bit of miserable sod in these matters. When Phil Hughes added to his debut 75 with two stunning centuries in his second Test, against Steyn, Morkel, Ntini and Kallis (and Paul Harris), who would have thought that he would be dropped just three Tests later? Not me, and probably not Phil Hughes. And almost certainly not the then bits-and-pieces allrounder Shane Watson, who replaced him and has since reached 50 in 12 of his 26 innings, the highest ratio of fifties-per-innings of any baggy green opener with 10 or more half-centuries.

Debuts, the deceitful little minxes that they are, have made many false promises. Particularly with legspinners. Narendra Hirwani took 16 for 136, Warne took 1 for 150. Kumble returned an inauspicious 3 for 170. Ian Salisbury twirled his web around Pakistan to take 5 for 122. Where did his 600 other Test wickets go? And maybe England should have stuck with Chris Schofield a little longer. Warne’s debut gave perhaps the falsest and cruellest promise of all to England fans – that Australia had unearthed yet another cannon-fodder legspinner to be marmaladed by England’s batsmen. That little reverie took one ball to shatter. It was sweet while it lasted.

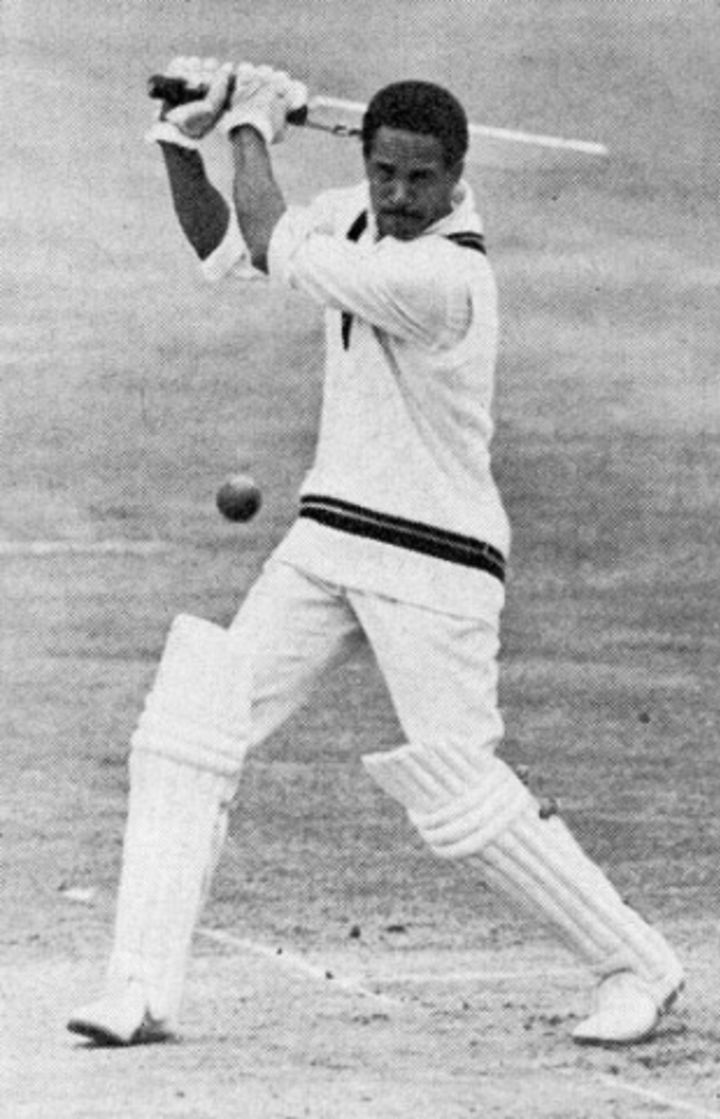

I remember when I first realised that Sachin Tendulkar could turn out to be the truly special player that he had been rumoured to be by the world’s cricketing press. It was when he reached 10,000 Test runs. It was clear at that point – in his 122nd Test, with an average of 57 − that the young man was destined for greatness. (Others had suspected it before then, but I like to reserve judgement on players until I am absolutely 100% sure about them, and the 10,000-Test-run barrier seems as fair a benchmark as any. Bradman, Sobers, Richards and Ken Rutherford I remain to be convinced about. The logic is simple: you can easily score fewer than 10,000 Test runs without being a particularly good batsman. But only good players reach 10,000. I therefore acknowledge that Tendulkar is a useful bat. Very useful, in fact – 95 international centuries constitutes a solid effort.)

Bangalore was one of the great highlights of his statistics-boggling career, a display of complete technical and tactical mastery that first transformed the game and then completed it, played with a vigour that suggests he may have several more good years left in him. Once he has ticked off 50 Test centuries and 15,000 runs, perhaps Wilfred Rhodes’ 31-year Test span will be the next major record in his sights.

Tendulkar’s continuing resurgence has been the highlight of a compelling microseries that again highlighted the desirability of macroseries. India finished looking like the world’s top side, playing three days of majestic cricket to seal the series, and Australia ended as a team with more question marks than a transcript of an unusually urgent police interrogation of a hard-of-hearing and inquisitive suspect.

Ponting’s captaincy on Wednesday attracted widespread criticism. To my layman’s eyes it seemed intended to distract the Indian batsmen through sheer bafflement. As they tried to figure out Ponting’s extremely well-concealed masterplan, they could easily have becoming distracted and perturbed, and smashed their own stumps down in confusion. Not really trying to take wickets when he needed to really try to take wickets was an obtuse approach. I have heard rumours that every night Ponting goes back to his hotel room, makes little papier-maché dolls of Glenn McGrath and Shane Warne, says to them: “Right, Glenn, you bowl from the bathroom end, and Shane, you take the bed end. I’m going for a snooze, and when I wake up I expect you to have bowled the opposition out. Night night.” Admittedly those rumours are ones that I have made up and said to myself, but still, no smoke without fire. There has to be some truth in them.

Back to Tendulkar, officially the world’s best batsman again for the first time in eight years. Tendulkar’s Test career is about to celebrate its 21st birthday, and is now the 11th longest of all time, and the fourth-longest not to have been interrupted by a world war. The three players ahead of him on that little list are Syd Gregory (58 Tests from 1890 to 1912; his longevity can be ascribed to an undroppably assertive moustache), Brian Close (England’s youngest and oldest post-War Test player, his 22 Tests splattered over almost 27 years, dropped six times in his first seven matches spanning three different decades, and proud owner of the most sporadic career in Test history), and dual-nation legend John Traicos, more of whom below.

The Mumbai Methuselah has missed just 14 of India’s 185 Tests in the almost 21 years since he first plonked his 16-year-old feet onto the Test arena, giving him a 92.4% attendance-at-work rate. This currently puts him fourth on the list of highest-percentage-of-possible-Tests-played of the 16 players with Test careers lasting longer than 20 years.

If he stays fit, continues to set his alarm clock, remembers to turn up, and is not lured away by the promise of a stint as lead cricket bat player in the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra’s forthcoming season of cricket-themed adaptations of the works of Mozart, then he could pinch the bronze medal from Sir Garfield Sobers (93% of Tests from 1954 to 1974). That is as far as he can hope to go. Two men remain unattainably in front: one-and-a-half South Africans and half a Zimbabwean. Dave Nourse did not miss a single Test of the 45 South Africa played from 1902 to 1924, and Traicos was never dropped in his 23-year Test career, from 1970 to 1993.

Traicos, who stands alone alongside Richard Hadlee in the Official ICC Catalogue Of Bowlers Who Have Dismissed Both Sachin Tendulkar and Keith Stackpole In Test Cricket, also remained undefeated until the final few months of his career. These facts in isolation might hint at one of the all-time great cricketing careers. Sadly for Traicos, his 23 years as an international cricketer were adorned by just seven Tests, sandwiching a 22-year sabbatical as a humble civilian – three games for South Africa before their ban in 1970, and four for Zimbabwe after their admission in 1992.

Recently unearthed relics from an archaeological dig at Kingsmead in Durban, where Traicos made his debut for South Africa, suggest that this Egypt-born son of Greek parents personally built a special altar with his cricket bag and sacrificed 100 head of oxen to almighty Zeus in return for (a) never being dropped, (b) having at least a 23-year-long Test career, and (c) not losing for the first 22 of those 23 years.

Zeus, always a deity with a wry sense of humour, granted Traicos’ wish with a flamboyant crack of his trademark thunderbolt, and the Egyptigrecozimbabweacsouthafrican tweaker skipped away in delight, visualising the forthcoming decades of batsman-shattering devastation that his tidy offbreaks would soon wreak. Zeus, meanwhile, giggled quietly to himself and muttered under his breath: “Sucker – you can have your 23 years undropped. And you can also have your seven Tests, your 18 wickets, and your bowling average of 42. Got you, Traicos, got you. Thanks for the barbecue. Yum, yum, yum.”

The King of Olympus then high-fived himself, and chirped: “I’ve still got it. Over 2000 years out of the media spotlight, and the Big Z has still got it.” It’s all in Wisden, if you read it backwards.

Some more on long careers in another blog later in the week. Unless the CIA suppress it. They fear needless cricket stats.

Lara has been deleted from the list of players the author is not 100% convinced about. Thanks to Anadi Bhatia for bringing the error to notice

Andy Zaltzman is a stand-up comedian, a regular on the BBC Radio 4, and a writer

Read in App

Elevate your reading experience on ESPNcricinfo App.