Past perfect

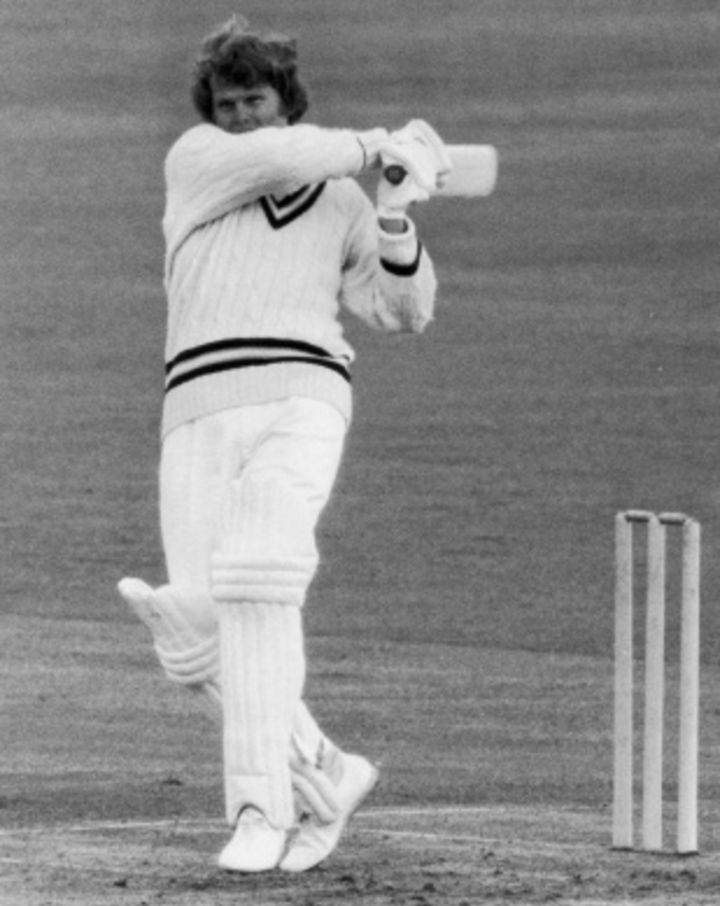

Talent, skill, cricketing smarts and a ferocious will to achieve: the world's most romanticised player had it all

There is this fascination about batting technique that tells its own story; it is one of styles and stylists, and of how each era has produced some remarkably skilled performers. Watching half an hour of Barry Richards was as much a revelation as a revolution, and that says a lot when memories of a Len Hutton innings some 20 or more summers before on a wet Basin Reserve surface were about as perfect as anything seen. With Richards, though, it was a matter of transcending the generation gap. He carried the art a little further and added his own charisma.

Richards knew the value and significance of such essential ingredients as perfect balance and classic technique mixed with economical strokeplay and footwork to match; a combination of instinctive mental and physical prowess. Sir Donald Bradman in an interview in 1992 said that he felt Richards was equal to Hutton and Jack Hobbs.

This is an interesting comparison. The memory of watching the Durban-born Richards bat on a damp pitch with awkward bounce on a blustery Southampton afternoon in May 1969 as wickets tumbled around him still provides remarkable insight into his impressive technique. He had been equally imposing three years earlier, when he was first sighted - in the nets at the Harlequins Club in Pretoria during a course for fast bowlers. Here he had an opportunity to express his uncanny, extroverted style. In both instances he gave a free-flowing and articulate exhibition.

In 1966 he drove with the aggressive emancipation of a batsman who had matured years ahead of his time: a classical example of textbook perfection. Three years later at Southampton, a century loomed as he conquered the bowling as well as the conditions, eliminating for a time the risky cut during a heavily rain-affected day.

Richards brought to the game a new dimension with his footwork. It was modern, designed to meet the demands of the varying and ever-changing pitch conditions of the late sixties and early- and mid-seventies in England and South Africa and Australia. There are purists, though, who will debate what constitutes modern techniques; of whether Richards or that other classical stylist Hutton had the better footwork. More up to date, perhaps, is Rahul Dravid, who understands equally the importance of footwork adjustment for the surfaces of Australia and the subcontinent and England.

Throughout his career Richards' manner spoke of a temperament that entertained audiences without the need to involve domination of the Australian type, with its chauvinist overtones. His ready run-making composure was evident from his pre-pubescent years. By 1963, when he led a South African schools side to England, his thinking had become well advanced, and he had developed an uncanny ability to look at a captain's field placings and know immediately the areas where he would score his runs.

Richards brought to the game a new dimension with his footwork. It was modern, designed to meet the demands of the varying and ever-changing pitch conditions of the late sixties and early- and mid-seventies in England and South Africa and Australia

It was instinctive and not something that might come from hours of studying, from a young age, Bradman's The Art of Cricket - which Richards incidentally did nevertheless. It displayed his methodical approach to the game, and of how he was smarter than the opposition captain and the bowler.

Richards also felt defence was another expression for attack; a modern captain's ideal opener. Get runs on the board and get them quickly: force the bowler to bowl the ball in the area the batsman wants, work him around and show him who is in charge.

A good example comes from his one Test series, against Australia in early 1970. It was Richards who was ahead of his more senior batting brethren when it came to unravelling mystery spinner Johnny Gleeson, who had the ability to bowl legbreaks and offbreaks with equal facility by holding the ball between thumb and folded middle finger of the right hand. Gleeson was on early in the first Test at Newlands, and while others battled long to spot the difference, it took Richards about half an hour: it was the legbreak if you spotted the thumb and finger; it was the offbreak if the bowler displayed the index finger above the ball. Others struggled until the fourth Test to untangle the finger mystery.

Richards did not have to go in search of glory or even greatness; it was always peering over his shoulder, staring at the bowler. It came from hours of practice, until what he needed was filed in his memory bank. To this he included his own addendum, the improvisation plans that were part of his ever-developing stroke-making repertoire.

It is hard, though, to compare Richards as a Test batsman to Richards the first-class classicist. He was blessed with staggering talent and an appetite for runs. No one can be judged on four Tests and a couple of centuries against what was, at best, a mediocre Australian side led by Bill Lawry. By his own admission, Richards has not been one for records. Be that as it may, first-class statistics give him 80 centuries and a career average of 54.74.

In 1970-71 it was his contributions - with an average of 109.86 - that helped South Australia win the Sheffield Shield. It was the season where his talent was given every chance to flower, and where he scored 325 (out of 356) in a day's play against Western Australia in Perth. That was his way: think big, score fast.

This article was first published in Wisden Asia Cricket magazine

Read in App

Elevate your reading experience on ESPNcricinfo App.