Why I want the word 'match-winner' erased from cricket's vocabulary

"Match-tilting" a better phrase for influential performances a team sport where an individual can't decide team results entirely

Jan 11, 2003. Auckland. India's nightmarish tour from seaming hell didn't seem to get any better: another bowling paradise awaited them in the sixth ODI. Chasing atarget of 200, Virender Sehwag bludgeoned his way to a superb 112, holding the innings together as technically more adept batsmen faltered around him. However, with 18 needed off 43 balls, he nicked one to Fleming. Over the next 40 balls, India scored 17 runs and lost five wickets. It was down to the last batsman, Ashish Nehra, to score one run off two balls. And he played the best - maybe the only - pull shot he has ever played to win the match. They say that in his match-winning abilities, Sehwag is comparable to Viv Richards.

Six years later. Hyderabad. Australia had posted a mammoth 350 on a placid pitch. Sachin Tendulkar stroked and glanced his way to a masterful 175, holding the innings together as technically inferior batsmen lent their hands in supporting roles. With 19 required from three overs, Tendulkar scooped one to short fine-leg. Over the next 11 balls, India added 11 runs and lost two wickets. It was down to Munaf Patel and Praveen Kumar to get eight off the last over. They tried with all their might, but they were no Ashish Nehra. India lost by three runs. How could they win, given that Tendulkar had scored a hundred?

There are three buzzwords I'd like erased from the cricket vocabulary: right areas, knowledgeable crowd and match-winner. If I can choose only one, I'll go with match-winner. All three are results of simplistic labelling, but the first two are fairly innocuous and occasionally even come to the rescue of commentators, while "match-winner" is more harmfully misleading. It leads to an unfair judgement of players based on factors outside their domain of influence - in blatant contrast to another of cricket's great platitudes, "controlling the controllables".

One thing that definitely cannot be categorised as controllable is the performance of your team-mates. Eleven players in a team means you have just an 11th of the match - or perhaps close to a third at most, if you are an absolute stalwart of the team - to seize. The influence of your masterpiece on the outcome still depends heavily on your team-mates' more humble renditions. Nehra ensured Sehwag's 112 did not go to waste. Ajit Agarkar's 6 for 41 in the 2003 Adelaide Test gave greater meaning to Rahul Dravid's 233. Without Graeme Smith and Hashim Amla's calm second-innings hundreds against Australia in Cape Town, even Vernon Philander's heroics might not have earned him a Man of the Match on debut.

Feb 26, 2003. Durban. India were up against England in a crucial league game of the World Cup. On a pitch that had something for the seamers, Andy Caddick and James Anderson went for over six an over. India posted a challenging total of 250. England would have fancied their chances of chasing it, but little did they know it was Ashish Nehra's night. Nehra swung the ball. Nehra found the edges. Nehra took 6 for 23 to smash England's batting to pieces. India won the match comfortably.

A fortnight later. On a seaming pitch in Port Elizabeth, New Zealand put Australia in to bat. Coming off a 300-plus score against Sri Lanka, Australia might have fancied a repeat batting display, but it was Shane Bond's day. Bond swung the ball both ways. Bond found the edges and hit the pads. Bond took 6 for 23 to reduce Australia to 84 for 7. But New Zealand did not win comfortably; instead, Australia did. Andy Bichel scored 64 to take them to 208. McGrath and Lee turned the game one-sided. McGrath and Lee were no Caddick and Anderson.

On his day, a player can demolish an entire team: that is one of the beauties of team sport. Well, it is not entirely true. A player can demolish only the portion of the opposition on which he has direct influence. If the opposition has its bases covered in other areas, he can only be a mute spectator to proceedings. Messi may score a hat-trick, but it is not his fault if the other team's forwards choose the day to have a ball themselves. A politician may sweep the vote in his constituency or even help fetch a few in others, but on the national level, it is often the party with better all-round strengths that wins. In other words, winning a game is determined not only by the performances of you and your team-mates, but also of the opposition players.

Mar 30, 1999. Bridgetown, Barbados. West Indies and Australia, the former and the present world-beaters, faced off for thethird Test of a five-match series. West Indies were desperate to regain the Frank Worrell trophy they had surrendered four years before. With the series tied at 1-1, and a target of over 300, West Indies knew they wouldn't last if they played for a draw. Their champion batsman, Brian Lara, having failed in the first innings, was in the mood to make amends. They decided to leave it to him. Lara made a mockery of an attack comprising McGrath, Warne, Gillespie and MacGill to take the West Indies to within seven runs of victory. And then it happened. Lara attempted to run down a shortish delivery from Gillespie to the third-man boundary, but instead edged it behind. Healy jumped to his left. Healy would have taken it nine times out of 10. As fate would have it, that nick was the 10th time. Lara survived. Curtly Ambrose and Courtney Walsh hung around for long enough. West Indies won. They say the 153 not out he scored that day is Lara's greatest innings.

Two months earlier. Chennai. Amid rising tensions between the countries, Pakistan toured India after nine years in 1999. The first Test, in Chennai, was a see-saw affair with India securing a first-innings lead. However, chasing 271 for a win on a deteriorating pitch against Wasim, Waqar, Saqlain and Afridi meant India needed a special innings from someone -- preferably Sachin Tendulkar, who had got out for a duck in the first innings. Battling severe back pain, Tendulkar executed his low-risk shots expertly and negotiated Wasim and Saqlain, the two major threats, to take India to within 17 runs of victory. And then it happened. Tendulkar, perhaps a bit casually, attempted a hoick that went straight up in the air. Wasim Akram steadied himself. Akram was no Ian Healy, but pouched it nonetheless. Tendulkar did not survive. The lower order collapsed. India lost. The 136 is one of Tendulkar's greatest, but it will never be a match-winning one.

Although luck is perhaps overrated in life, it is underrated in sport. Those little moments that could have so easily gone the other way sometimes play a decisive role, which is often realised only retrospectively. What if, in the 2005 Edgbaston Test, Brett Lee had hit the full toss that preceded Michael Kasprowicz's wicket behind square, or even edged it, for four? What if Allan Donald had responded promptly to Lance Klusener's call? More recently, what if JP Duminy had heard Farhaan Behardien's call for Grant Elliott's skier in the World Cup semi-final? The list of what-ifs has no end. With the line separating victory and defeat so fine, we must admit that it is naive to suggest a linear extension from a single player's performance to the outcome of the match. To better determine a player's contribution, we must try to imagine where the team would have ended up without his services. It is time to do away with "match-winning"; let us contend with the weaker, but more accurate, "match-tilting".

Mar 23, 2003. Johannesburg. Ricky Ponting was a big-game player. He was the leader of the Australian side and he would show what leading from the front was all about. Ponting started slow; he had decided to get his eye in before going for big shots. Get his eye in he did, and go for big shots he most certainly did. With Damien Martyn for company, he flayed the hapless Indian attack and put Australia in the driver's seat of a bus that was miles ahead of India's. His bowlers were too good for India's star batting line-up. The main threat, Tendulkar, was caught in the first over. And Sehwag, the only dangerous-looking batsman, misjudged a single and was run out. Australia won the World Cup.

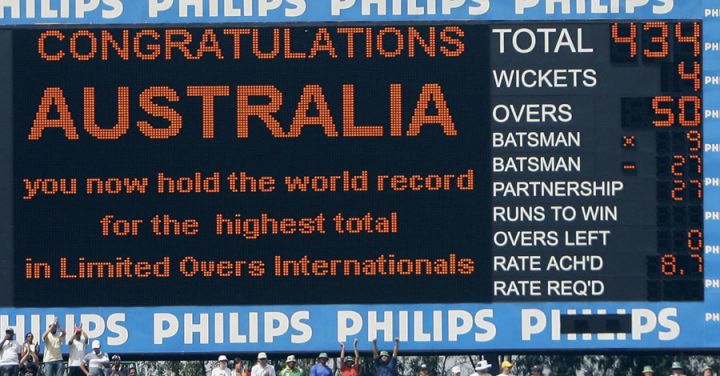

Three years later. Same venue. Australia and South Africa were tied at 2-2 in a five-match ODI series. Australia batted first and Ponting got his eye in. He then proceeded to flay a much superior attack on his way to 164 in a record team total. But his bowlers were not so good this time: everyone except Nathan Bracken and Michael Clarke went for over eight an over. The opponents were not cowed by the target: they staged the most daring counterattack in ODI history. Luck teased the Australians: Bracken dropped a regulation catch off Herschelle Gibbs when he was on 130. Ponting's brilliant 164 was as match-winning as any. But Australia did not win the match.

If you have a submission for Inbox, send it to us here, with "Inbox" in the subject line.

Vijay Subramanya is a grad student in computer science. He hopes his blog, which has begun cautiously, flourishes soon, like a Jayawardene innings

Read in App

Elevate your reading experience on ESPNcricinfo App.