Amazing Grace

In the late 1800s, one man was synonymous with cricket, and enchanted all who came to see him bat. Truly was he nearly as big as the game

David Frith

01-Aug-2010

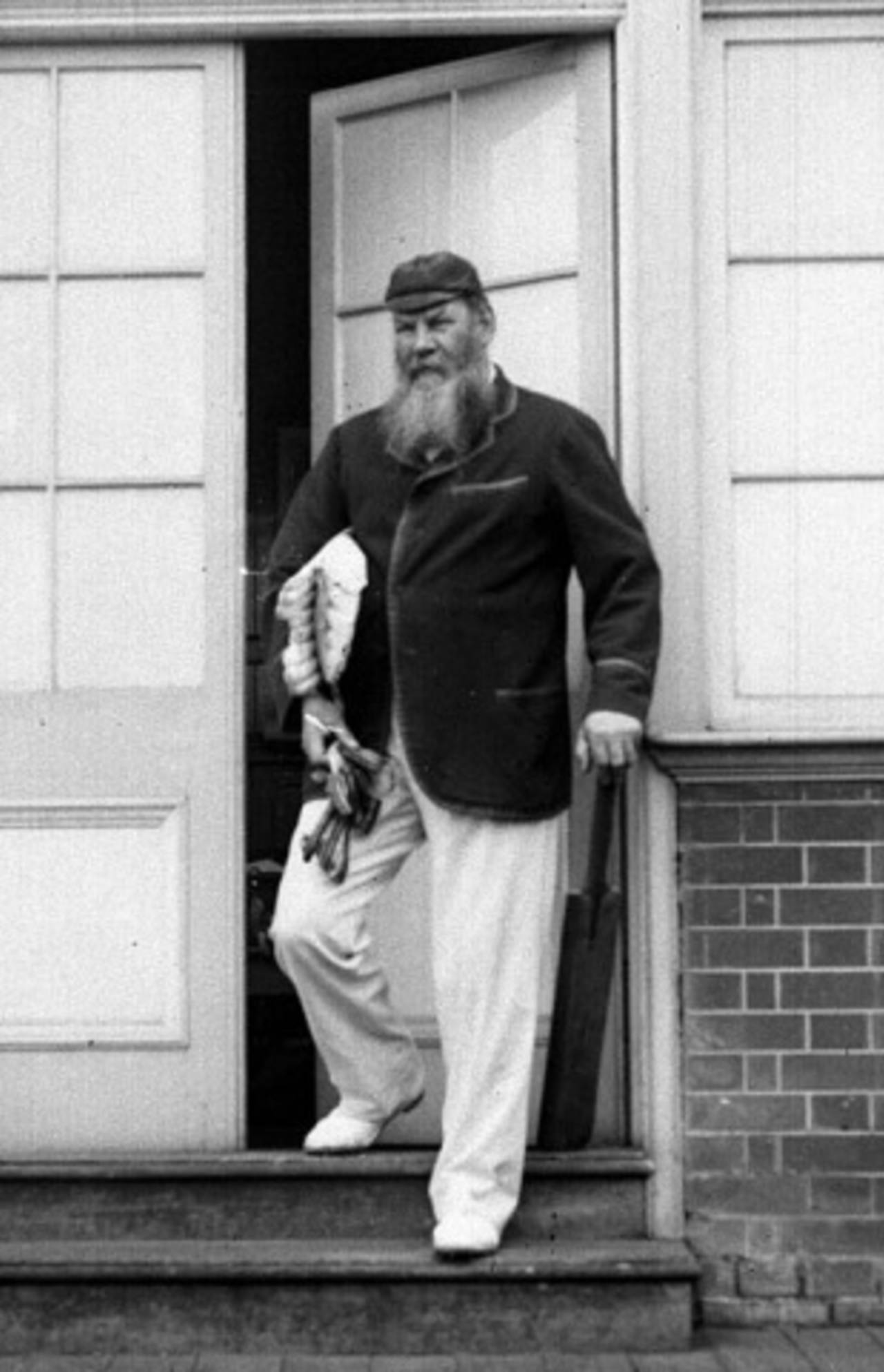

Grace: drew gasps of admiration • PA Photos

Today's iconic image of William Gilbert Grace is a little misleading. The waistline was not always so protuberant and, equally obviously, the beard was not always streaked with grey. One of England's finest amateur athletes in the 1870s, "WG" became a truly legendary figure not only on the strength of his phenomenal performances on the cricket field over several decades but through his extraordinarily dominant - sometimes bumptious - character.

In a cricket environment that few moderns would comprehend, having played his first first-class match in 1865, when just short of 17, and failed to score, WG began totting up first-class centuries the following year with a huge 224 not out for an England XI against Surrey at The Oval. By the time of his final first-class appearance, just over 40 years later, he had laid down statistics that seemed likely to be forever unmatchable.

And in one sense they have been just that. While he was not to be the only batsman ever to reach 100 centuries, in his day a run truly was a run. It was one of cricket's all-time sensations when he registered 10 centuries in 1871. Few pitches in the 1870s and 1880s were batsman-friendly, and WG drew gasps of amazement and admiration as he clamped down on fast shooters on imperfect pitches - even at Lord's - and whipped the ball to the boundary. His performances amazed and enchanted all who saw him play and read about him in the newspapers, especially in 1874, when he became the first to pass not only a thousand runs but a hundred wickets. Two years later he set yet another breathtaking mark, with the 1000-200 double.

Although he was no lofty intellectual, from his rural boyhood he had devised a technique that took batting from its middle ages of development into something that moderns will instantly recognise. In the only brief film clip of WG Grace batting, in which he makes a few hits in the nets for the newly invented movie camera, what catches the eye is that large waistline and grizzled beard as he plays with a slightly angled bat, showing disdain for the ball. But here was the man who, when young, worked out a way of responding to all the bowling that came his way, pioneering the combination of forward play and back, cleverly using his feet, and venting that extraordinary confidence first perceived by his mother as she played with her little lad in the Gloucestershire apple orchard.

His reputation for gamesmanship and as a bully was emphasised with each passing summer, and was facilitated by timid umpires and opponents and sycophants who, overwhelmed by his force of character, allowed him to prevail. In 1876, one of his greatest summers, in a non-first-class match for the travelling United South XI against Twenty-Two of Grimsby he was excused a plumb lbw when 6 because, conceded the umpire, the crowd had indeed come to see him play. He went on to 400 not out. In reality, as the players left the field, the scorer made it 399, but WG urged him to round it up to 400, and that was exactly what he did.

It was a warm-up for one of the most purple of patches, as shortly afterwards the cricket world marvelled at the first triple-century, 344 for his beloved Gloucestershire in the follow-on against Kent at Canterbury in 1876. He then went straight back to Clifton and made 177 for his county against Notts. And with the visiting Yorkshire players now expecting him to be exhausted, he followed it all with 318 not out against them at Cheltenham.

There could now be no doubt that his was the most famous face in Britain, apart from Queen Victoria's and possibly Gladstone's, and his popularity was enormous

Came 1895 and all of England was poised to celebrate his 100th first-class century. He made sure with 288 against Somerset at Bristol, and the banquets and testimonials began. WG demonstrated how he could drink anyone under the table, coupling his love of companionship with an aversion to long speeches. Three years later the event of the summer, the Gentlemen (amateurs) v Players (professionals) match at Lord's, was dedicated to his 50th birthday. There he and all the other players were filmed as they walked by the pavilion. Grace's amateurs lost in a thrilling finish, but there could now be no doubt that his was the most famous face in Britain, apart from Queen Victoria's and possibly Gladstone's, and his popularity was enormous.

Although revered by the nation, Grace sometimes aired an abrasive nature that naturally caused upset. Charles Kortright, the fastest bowler of the age, once knocked his castle over and said, as WG reluctantly departed: "Surely you're not going, Doc? There's still one stump standing!"

Nor did his two trips to Australia - in 1873-74 and 1891-92 - do much to enhance his reputation. There was no diplomacy about him when he perceived local umpires as inept or biased. So local spectators let him know what they thought of him. That first tour had been his and Agnes' honeymoon, while on the second tour, financed by the Earl of Sheffield, Grace again took his wife, now with their two youngest children as well, and all for a very fat fee. Alas, if it was thought that the great cricketer's presence in Australia would counter republican sentiments, His Lordship had picked the wrong man.

The great George Lohmann found Grace too much during that tour and stated he would never tour with him again, "not for a thousand a week". The skipper simply could not help himself. It was the same back in 1878, when Billy Midwinter of Gloucestershire defected to the touring Australians. Grace took a hansom cab from The Oval to Lord's and kidnapped the player just as he was preparing to bat for the touring team against Middlesex, escorting him to the county match over the river.

WG's other overseas tour had been to North America in 1872, where his celebrity status was confirmed as the collection of carefree amateurs roughed their way through often difficult territory and capitalised on an enthusiastic social life.

A pioneer in many ways, Grace was among the first cricketers to endorse products•ESPNcricinfo Ltd

Test cricket in the 19th century was a narrow avenue by comparison to the cluttered highway of today. Grace played no more than 22 times for England, fittingly scoring his country's maiden Test hundred, 152, on his debut against Australia at The Oval in 1880 (when two of his brothers, EM and GF - Fred - also played). Six years later he made 170 against the visiting colonials, also at The Oval, though it was not until 1888, for his 10th Test, that he was appointed captain. He was pre-eminent and he was an amateur, but the tall and often brusque West Country doctor was not actually an establishment figure and was not quite of the social standing of Lord Harris, AG Steel and AN Hornby.

It is less likely that any of those three would have run out young Australian batsman Sammy Jones as he was tapping down a divot, as WG Grace did in the famous 1882 Oval match, which saw the birth of the Ashes legend. This so fired up "Demon" Spofforth that he bowled with an irresistible fury that brought him a further seven petrified English wickets - though not WG's: he made 32 out of the sickly 77, leaving the mother country eight runs short of victory.

His last Test was at Trent Bridge in 1899, soon after the death of his daughter Bessie. (A son, Bertie, died in 1905). At 51 he knew he had had enough at the highest level: "I can still bat," he lamented, "but I can't bend!" A painful breach with his beloved Gloucestershire after 30 years led to a spell as manager and match organiser for the new London County club at Crystal Palace from 1900 to 1904, when he took the opportunity to invite old friends like WL Murdoch and promising young players to enjoy a few matches each summer.

He so loved the game that he played as long as he possibly could, his last first-class appearance coming in 1908, at The Oval, where his major cricket had begun 43 years earlier. His final innings in any match was 69 not out for Eltham in July 1914, when he was 66. It was estimated that he had scored over 101,000 runs in all kinds of cricket (with at least 220 centuries), in addition to taking over 7500 wickets with his cunning round-armers.

His bowling was accompanied by chatter that would be appreciated by modern chirpers in the field, though it was frowned upon in an age when courtesy and good manners were cherished. Naïve batsmen were sometimes invited to look at a flock of birds (sometimes imaginary) flying over a corner of the field - always directly across a dazzling sun of course. At his favourite position of point, he liked to air his views on batsmen and the state of the game, a practice even more annoying in view of his surprisingly high-pitched voice.

With that failing voice he cursed the sinister German zeppelins circling over London with their bombs at the ready. The stress brought on the stroke which killed him in October 1915.

Where did the "Doctor" come from? It can seem as if WG Grace spent all his time either playing cricket or raising a family or playing golf, lawn bowls or curling, or out with the beagle hounds or fishing. But he qualified as a medical practitioner in 1879 and was a conscientious GP for some years. But cricket was his life. Some have written of his "emotional immaturity", his limited reading, his rather off-hand attitude towards wife Agnes. Perhaps one of his recorded utterances best sums it up: he believed that there was no such thing as a crisis, only the next ball.

David Frith is an author, historian, and founding editor of Wisden Cricket Monthly