The Ashes Masters

David Frith

|

|||

|

Related Links

Players/Officials:

Sydney Barnes

| Alec Bedser

| Allan Border

| Ian Botham

| Jack Gregory

| Jack Hobbs

| Jim Laker

| Harold Larwood

| Dennis Lillee

| Bill O'Reilly

| Frederick Spofforth

| Herbert Sutcliffe

| Victor Trumper

| Victor Trumper junior

| Frank Tyson

| Shane Warne

|

|||

Dozens of cricketers since 1882 might well be termed "Ashes masters", but for the purposes of this exercise only eight from England and eight from Australia have been chosen. The selection will not please all. How could Wilfred Rhodes or Ray Lindwall miss out? The omission of Walter Hammond, perhaps the greatest of the sacrifices, is explained by his overall record in Ashes Tests. He may well have been the finest cricketer ever to wear an England cap, but his country won only two of the seven Ashes series in which he featured, and Grimmett and O'Reilly often tied him down with a leg-stump line. Similar anguish attaches to the exclusion of Len Hutton, still holder of the individual record with his awesome 364 at The Oval in 1938. But the same rules of assessment apply: England were successful in only the last two of Hutton's six series, in neither of which did he personally perform all that remarkably except as captain.

This brief is concerned with technical triumph and with the changes that have swept the game. Would a master of 100 years ago - or 50 - have prospered in modern company? Have techniques really improved? Have technology and communication expanded to such a degree that cricketers need to be even more skilled than their predecessors to survive in the top flight? England's 1920-21 captain J. W. H. T. Douglas was so helpless against Arthur Mailey's devious spin that he resorted to watching him through binoculars. Today Douglas would be studying his tormentor through close- up playbacks on a laptop, a loquacious analyst by his side. Whether it would have made any difference is anyone's guess.

The four Englishmen selected from the pre-1939 period are Sydney Barnes, Jack Hobbs, Herbert Sutcliffe and Harold Larwood. S. F. Barnes's name still comes into discussions about the supreme bowler. The only cine-film of him was shot from long range almost a century ago, and much later from close quarters when he was 80. His arm even then brushed his ear. Photographs show a tall, glowering man. Forty years ago, when he was in his nineties, his stern gaze sent a shiver down my spine. "I spun the ball!" he barked, after an innocent suggestion that he must have cut it with those long, bony fingers. Beyond his amazing Test stats, Barnes was a major example of the force of high skill backed by assertive character.

England's express bowler of the 1950s, Frank Tyson, for years a citizen of Australia and a seasoned coach, remembers George Duckworth's story about playing for Lancashire's Second Eleven against Staffordshire, for whom Barnes, then in his fifties, was about to open the bowling. Duckworth enquired innocently why more than half the lads were padded up, and was told: "SF is playing, and we shall all soon be wanted!" Tyson recalls not only Barnes's mean character but his "scraggy, spare physique" and long, tapering fingers, "heaven-made for a man who refused the description of 'cutter' in favour of 'spinner', a player who would take the new ball and bowl curvaceous spinners!"

Graeme Fowler, the Lancashire and England left-hand batsman and an occasional wicketkeeper, holds an ECB Level 4 coaching certificate and is among the multitude still fascinated by Larwood. Because of the sensational nature of the 1932-33 Ashes series, irrevocably dubbed "Bodyline", the tough Nottinghamshire fast bowler at the centre of it remains a vivid figure three- quarters of a century later, thanks to film footage showing his imposing action, his strong physique and his high velocity. Yet Fowler has calculated that the England wicketkeeper would run 12 paces up to the stumps to take a throw-in after Larwood - and Fred Trueman for that matter - had bowled. When Fowler was "trying to keep wicket" to Michael Holding in Lancashire matches he stood 25 paces back in order to take the ball at the right height. At first slip for Wasim Akram he stood 30 paces deep. Faster pitches? Bigger, stronger fast bowlers? Fowler believes so, though he may be unaware that Trueman, Alec Bedser, Brian Statham and most of the old fast men were proud of having seldom if ever broken down, and perceived their latter-day successors as rather fragile.

Fowler, while accepting that the moderns are not necessarily better, is confident of the benefits of today's scientific training methods and data access, not least to study the opposition. All the same, at a time when there was scarcely any technical wizardry, there was no secrecy about Don Bradman's hesitation against the short ball. This was because England's wicketkeeper Duckworth put the word around following the 1930 Oval Test. It might only have been many years later that it was fully realised that leg- spin, and specifically the deception of the googly, troubled Bradman more than anything else. England's Ian Peebles bothered him, as did The Don's wondrous compatriot Clarrie Grimmett. And then there was that fatal final googly from Eric Hollies.

Fowler and the other assessors who were invited to offer their opinions do seem agreed on one cardinal point: that eminent players from one era would be successful in any other, although the old-timers would almost certainly need to make a few adjustments to technique and approach - and possibly even equipment. Jim Parks, the former Sussex and England wicketkeeper-batsman, goes further: he believes that many of the champion run-makers of old would have been even more successful on today's "stereotyped" pitches. Modern powerful bats and the absurdly shortened boundaries support this contention - though Hobbs and most of the top 20th-century batsmen, offered a choice, would surely have clung to their lightweight "touch" bats. As for Larwood, Parks's father (who also won an England cap) was among the almost unanimous majority who nominated him as the fastest they ever faced. His Sussex team-mate John Langridge, who spanned both eras, rated Tyson faster still.

Keith Stackpole, Australia's bold batsman of the Simpson/Lawry/Chappell era, an unusually thoughtful cricketer who has an Ashes double-century to his name, recalls the resentment Australians still felt towards Larwood long after Bodyline. "But how times have changed. If he was playing today crowds all around the world would be flocking to the grounds to see him bowl."

Would the many changes to cricket's laws and playing conditions have helped or hindered Larwood? The back-foot no-ball law allowed him to bowl from a bit closer, but the broadening of the lbw law, allowing batsmen to be given out to balls snapping back from outside off stump, at last relieved the acute frustration felt by bowlers, even if the amendment came too late for Larwood. After the broadening of the bowling crease in 1902, the slight reduction in the size of the ball in 1927 and the increase in the size of stumps and bails in 1931 (and notwithstanding the clampdown on the use of resin by spinners), this lbw reform remains almost the last of the law changes to favour bowlers. All the other tinkerings since the Second World War - aside from the "intent" clause in the lbw law to combat deliberate padding-away - have been designed to make life easier for batsmen, undoubtedly to curb early finishes and loss of television and gate revenue.

Hobbs and Sutcliffe became an institution, skilful and calm, possibly even now the ultimate symbol of the perfect opening pair. Parks recalls his father's telling comment that Hobbs played his strokes later than anyone else, with a flair for steering the ball through narrow gaps. "In modern cricket," says Parks, "where defensive fields are set far more, this ability by Hobbs and Sutcliffe to place the ball would have been very effective, more so than brute-force batting." Although it was frequently said of him that he was the "perfect batsman", Hobbs wrote in a coaching book: "I myself am always learning something, and I believe this can be said of most cricketers, no matter how eminent." This resolve never to allow one's technique to stagnate seems crucial to long-term success.

The key to Sutcliffe's phenomenal Ashes success - his average of 66 is second only to Bradman's among regular players - was his skill in playing just within his limitations, and usually on the leg side, whereas Hammond favoured the off. His brilliantined hair shining, Sutcliffe hooked bouncers like no one had previously done. His temperament was exceptional too, the best that Bradman ever saw, or so he said. It was the same with another Yorkshire- man, Stanley Jackson, who averaged 48 in three-day Ashes Tests before the First World War on uncovered pitches: worth at least half as much again today?

England's other four Ashes masters are Alec Bedser, Frank Tyson, Jim Laker and Ian Botham. For three of them, extraordinary impact on one Ashes series is the marker, while Bedser demands inclusion because of his Atlas-like role through four punishing post-war series, culminating in the recovery of the Ashes in 1953 when he took 39 wickets. Bedser had much in common with Barnes, not least an uncompromising personality with little scope for humour. Tyson recalls how Bedser could wrap his "ham-like" hand around the ball and make it disappear: helpful if you want to manipulate it as a medium-fast bowler, as a string of Bradman dismissals testifies. Bedser discovered an ability to bowl a fastish in-dipping leg-cutter, the result, Tyson says, of an altered grip and rocking-horse action.

As for Tyson himself, the 1954-55 Ashes series will always bear his name. The "Typhoon" began at the Gabba with a run-up from near the sightscreen and figures of one for 160, but the rest of the series belonged to him. Maybe it was because he cut back his run. Maybe he was inspired by being in his hero Larwood's adopted home of Sydney. Certainly it was because this muscular academic gave everything he had. He felt morally obliged to use what Nature had given him while it was there. Tyson has reflected that "perhaps bowlers such as Larwood and myself were created with just one purpose in mind: to win the 1932-33 and 1954-55 series". He had idolised and been inspired by Larwood, and recalls wearing, like all fast men of that era, the same kind of boots as Larwood wore: robust but heavy, with thick leather soles and heels.

Tyson was not the only bowler at that time to land his front foot way ahead of the popping crease. It led to an oddity during that 1954-55 series when he read in a Sydney tabloid that Larwood, his hero, was condemning him for coming down so far beyond the crease: "Replay Tests - Tyson Not Fair!" screamed the placard. A few years later the front-foot no-ball law was introduced. When Sir Donald Bradman objected - and he carried on doing so almost until his last breath - it was cynically suggested that he had his own portfolio of records in mind and wanted to support the brotherhood of bowlers all he could. This did not accord with the fact that he supported other law revisions favouring batsmen, such as the move to ban the thick clusters of leg-side fieldsmen.

While Tyson would be many people's nomination as the fastest bowler ever (he bowled the only ball to Parks that the batsman simply didn't see: "it was frightening"), his contemporary, Laker, may have been the finest off- spinner. The pair contributed vastly towards making the 1950s England's most rewarding decade. In the 1956 Old Trafford Test, Laker took 19 for 90 on a helpful pitch and with lots of close fieldsmen, especially on the leg side - a dream-like performance, rendered the more bizarre by the failure of his aggressive left-arm partner Tony Lock to take more than one wicket in 69 overs of frantic endeavour. Stackpole quizzed Lock about this some years later and was told: "Destiny was against me: catches fell short, batsmen played and missed, appeals were turned down, nothing went right for me." We should ponder that word "destiny".

Parks recalls Alan Oakman returning to Sussex after holding five catches in Laker's leg-trap in that famous Test and saying he had heard the deliveries fizzing through the air on their way down. Parks himself liked to get down the pitch to spinners, but with Laker it seemed impossible: "The ball was never quite there." Laker's wondrous figures seem secure from challenge not only because that pitch was unprotected from rain, but because the squadron of leg-side catchers was soon outlawed. Nonetheless, although the Australians sought retribution when Laker finally bowled on their firmer surfaces in 1958-59, he was never clobbered during England's grim 0-4 drubbing - though his swollen finger kept him out of the Test at Adelaide, where the pitch was fine and the square boundaries short.

|

|||

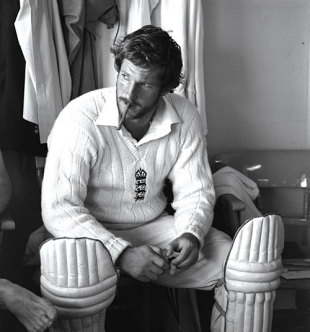

And so to Botham, the bold young man whose derring-do thrilled the nation. Putting to one side the matter of his failure against the strongest team of the time (West Indies), the focus is best directed to the super- confident approach which gave him physical and psychological dominance over Kim Hughes and his Australians of 1981. Botham's bat was straight and ever ready to plunder even Lillee's ferocious pace, while his bowling, before a back operation dulled his powers, was often overwhelming through pace and late swing - all this and smart catching plus a personality that mimicked a real-life battlefield warrior.

He had been helped to his peak by the best of mentors at Somerset, the perceptive Tom Cartwright and the teak-tough Brian Close. But Stackpole suspects that Botham's success might also have owed something to his apprentice seasons of grade cricket in Melbourne at a time when the competitive spirit there was more marked than in the county game. Botham was a prime example of ebullient character supporting technical skill in a very effective way. It poses the question: what heights might technically sound batsmen such as Keith Fletcher and Ian Bell have reached if they had been endowed with Botham's bullish personality?

Tyson recalls the future "Sir Beefy" as a trainee cricket scholar sent out from England to Melbourne and working at the players' hotel during the 1977 Centenary Test. It was an inspiration to be surrounded by scores of old-time Ashes heroes, and while he was staying with the Tysons (a nice historical link) news came through of Kathy Botham's first pregnancy. Tyson had already decided that Botham was probably the type who "never wasted a nanosecond doubting that there was a ball he could hit for six or with which he could rattle the stumps". And Botham's contemporary Fowler once said: "He is the school bully, the school champion. You can't beat him at anything. If you do, he beats you up. If you stand up to him you are basically offering yourself to his mercy... a more generous man and firm friend you could not wish to have." A triumph, then, of sheer Churchillian character.

Three of Australia's selected Ashes masters are from the modern era: Dennis Lillee, Allan Border and Shane Warne. All have been objects of worship in this mass-media age, and only Border knew prolonged hardship, partly because of the depletion of Australian talent at the start of his captaincy, when some key players embarked on the disapproved tours of South Africa.

In 1972 in England, Lillee's partner Bob Massie returned an incredible 16 for 137 on debut in the Lord's Test, causing tour selector John Inverarity to exclaim: "We've unearthed a top bowler here!" To which fellow-selector Stackpole added: "Don't forget the fella at the other end!" But only after recovery from a career-threatening back injury did Lillee reveal his true greatness. Previously a snarling long-haired tearaway, the rebuilt Lillee became the world's premier fast bowler, still snarling but with a refined approach to the bowling crease, "so efficient and rhythmical, probably the best fast-bowling action ever", believes Stackpole.

Lillee's captain in most of his early Tests, Ian Chappell, thinks the best thing about him was that he never asked for a defensive fieldsman: "He was not worried about his average, only about getting batsmen out." Anyone who ever accused Chappell of overbowling Lillee would be told: "Have you ever tried to take a bone off a Doberman?" Lillee finished with a then-record 167 England wickets at only 21, and he did it with such unbending determination that Barnes himself would have nodded approvingly. Recently Bob Willis pictured Lillee's stock outswinger and classified it as a fast leg- break, while one of England's wicketkeepers of the period, Bob Taylor, remembered Lillee not only for his mean bouncer but for his "immaculate line". He was a master bowler, and for years since retirement has been a shrewd coach.

Fighting spirit and determination lift Border into this selection. His batting was not pretty, but no tougher character ever played Ashes cricket. His final figures are awesome: 11,174 runs from 156 Test matches, 3,548 in 47 against England. With the distinctive left-hander's chop-cut, his exploitation of the third-man region left vacant by England captain Willis remains a clear memory, as does the sequence of marathon innings in 1981 despite a broken finger. Stackpole admits to having found Border the most difficult batsman on whom to commentate during radio and television stints: "His pugnacious style lacked any real flair or elegance, and seeing him play the same type of innings left me not really wanting to see more of him!" This back-handed tribute was surely echoed by all of Border's opponents. His resolution helped drag Australia from mediocrity to the top, especially against England, laying the foundation of a golden period for the three skippers who followed him. He was a chunk of finest ironbark.

Warne was the swaying, enticing palm-tree, hula skirts all around and lethal coconuts dropping on to batsmen's heads. Stackpole sees him as a "likeable rascal", and identifies the source of his success as not only power of wrist and fingers and boldness of character but his outstanding stamina too. "In some ways he was a bit of a con artist. He seemed to have certain umpires in his pocket. He played the mental game with batsmen even before he had bowled a ball." Warne spun, grunted, leered and teased his way to an astonishing Ashes-record 195 wickets, starting with that "ball of the century" to bowl Mike Gatting at Old Trafford in 1993 (he is the only bowler in Ashes history to hit the stumps with his first delivery) and finishing with the stumping of Andrew Flintoff at Sydney in 2006-07.

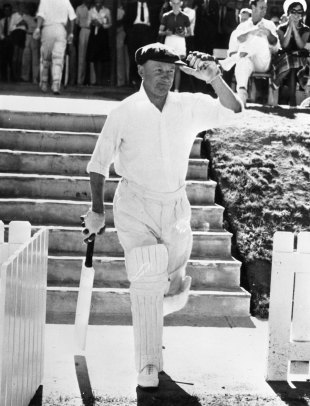

The five Australian Ashes masters pre-1950 are Fred Spofforth, Victor Trumper, Jack Gregory, Bill O'Reilly and Don Bradman. Moving film goes some way to illuminating the style and method of the last two, and there is a little footage to show the swashbuckling Gregory, batting bare- headed and without gloves, and bounding in to bowl off 15 yards with a kangaroo leap at the climax. This giant was also a superb slip fieldsman, and his 15 catches in the 1920-21 Ashes whitewash remain a record for any Test series, a phenomenon largely explained by a revision of the role of the wicketkeeper, who for some decades now has been diving full-stretch after almost everything edged or flicked by batsmen either side of the stumps.

All too briefly the tall and suntanned Gregory was the world's most dynamic and exciting cricketer. England might have won the 1920-21 series, instead of losing all five Tests, had there been no Gregory. Back from the horror of the Western Front, he crashed through England's batting with 23 wickets, held those 15 catches (standing very close at slip to Mailey's dipping spinners) and banged 442 runs at 73.66. And the torment went on for another two series.

|

|||

Earlier still, "Demon" Spofforth had been the prime instigator of the Ashes legend. Had he not blasted out 14 England batsmen at The Oval in that celebrated 1882 Test match to gain the "Colonials" a stunning victory by seven runs, there would not - for a while at any rate - have been the first and most lasting obituary of English cricket. The tall, unsmiling "Spoff" had been a wild fast bowler, inspired as a youngster by "Tear'em" Tarrant when the 1863-64 English team were in Sydney. Spofforth also happens to bear an extraordinary facial resemblance to Lillee. The pair had another thing in common: after explosive arrivals, they later concerned themselves less with attaining maximum speed than with shrewd variations.

Like Lillee, Spofforth became entangled in controversy, perhaps the most inflammatory about his innovative spikes, which opponents believed were deliberately used to chop up the soft pitches for his bowling partner. Today, with the game belonging to batsmen, the ICC and its umpires would have had a collective fit if Spofforth had flattened an opponent with a straight left, as he did Lancashire's Dick Barlow when he complained about those spikes.

A few unworthy film clips of Trumper survive, so assessment also relies heavily, indeed almost solely, on the words of his contemporaries, none more authoritative than those of M. A. Noble, shrewdest of captains, who analysed him graphically: "Our Vic" seized the initiative by disrupting bowlers, knocking them off a length just as Macartney did half a generation later, playing the ball very late. Trumper even cut Len Braund's slow-medium leg- theory to the off-side boundary. "Spoil a bowler's length and you've got him," was one of his basic beliefs. Watching the bowler's hand with great intensity and wielding a light bat made even lighter (he shaved away some of the lower wood at the rear), he would sometimes change his mind in a flash mid-stroke. If he had a weakness, Noble declared, it was a disinclination ever to play himself in.

While Trumper listened politely to advice, "Tiger" O'Reilly asserted that if ever you see a coach approaching, you should run for your life. O'Reilly's best protégé, Kerry O'Keeffe, was among the many who received that caution: "If they tell you you're bowling too quickly, thank them for their advice and forget it." The veteran believed that the youngster was ruined by too much technical analysis during his two seasons with Somerset. (How O'Reilly would have rejoiced in Virender Sehwag's recent pronouncement that "I don't believe in technique. I believe in performance.") This big, genial, bald-headed man from the bush taught himself, and never stopped thinking about the game and its complexities. Brisk leg-spinners, top-spinners and wrong'uns earned O'Reilly 102 England wickets in four series in the high- scoring 1930s, and if scowls, grunts and sneers could take wickets he would have had twice as many. Suffice to say that Bradman, despite the bad personal relations between them, regarded O'Reilly as the finest bowler he ever saw.

Ian Chappell firmly links O'Reilly and Warne for their aggressive approach and common belief that "you have to go after batsmen in the same way the really good fast bowlers approach their task". He cites O'Reilly's reply to the chap who asked if he had ever "Mankad-ed" a batsman (run him out for backing up too far): "Son, I never found one that eager to get to the other end!"

All our assessors remarked upon the reluctance of many modern batsmen to use their feet against spin bowling, some also noting that umpires seem more ready these days to grant lbw appeals. This is where Fowler's reasonable conviction concerning advances in sports science collides with entrenched and perhaps even sentimental thinking. He points out that Paavo Nurmi's world mile record in 1923 was four minutes ten seconds; by 1999 this had been reduced to three minutes 43 seconds. The javelin record distance has stretched by almost 50% in 70 years. "The game and life have moved on," says Fowler, and there is no denying that.

And so to the batsman whose name has surely been uttered or set in type more often than any other over the past 80 years. What made Bradman great? Clinical measurement revealed that his eyesight and reflexes were not superhuman. It was determination, sharp intelligence, marvellous footwork and an insatiable run hunger that made the difference - that, and possibly a discovery made surprisingly late. A club cricketer/coach from Cheshire, Tony Shillinglaw, has concluded after studying computer analysis that the practice conducted by the solitary boy Bradman - hitting a golf ball against a water tank with a cricket stump - caused him to use a rotary arm movement, which served him so well. He was far from being the only batsman to lift the bat back towards second slip (Greg Chappell also believes that the traditional straight backlift is a mistake), but this rotary movement, allied to his superb reflexes and his mental strength, made him what he was.

Bradman's top-hand grip wasn't conventional either. But any cricket student confused by this might reflect on the retort from Bill Andrews of Somerset who, when advising a boy to alter his grip, was told by the lad: "But Don Bradman held the bat like me!" After a moment's thought, Bill said, "Well, just think how many runs Bradman might have made if he'd held the bat properly!"