That languid, Gower summer

In 1985, at the height of his powers, David Gower was flawless, influential, and a lesson to eight-year-olds on what style meant

Ed Smith

04-Oct-2012

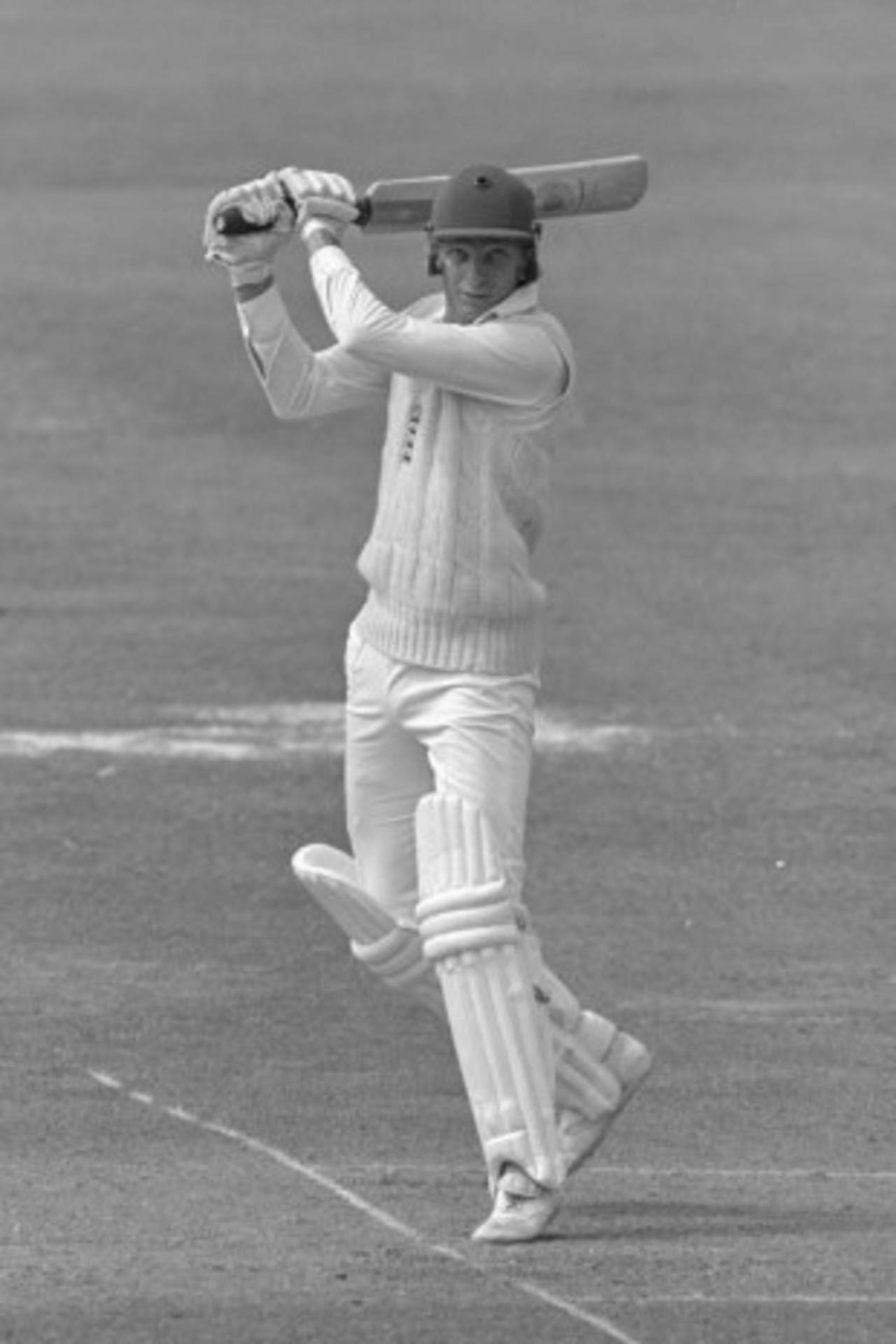

"High" Gower, at Lord's in 1985 • Adrian Murrell/Getty Images

Who is your favourite player? It's only half a question because our preferences change with age. As with novels, we are susceptible to different cricketers at different stages of life. The showman, the stylist, the battler: there will be a time for each of them.

In 1985, as a cricket-obsessed eight year old, I was just about old enough to grasp the idea of style. In fact, it may have been a cricketer, David Gower, who introduced me to the concept.

That Ashes summer of 1985 seemed to be a never-ending highlights reel of languid Gower cover drives and nonchalant late cuts. Can an eight-year-old really distinguish an elegant cover drive from all the others? Perhaps only just. But like many childhood experiences, watching cricket was informed by the adult conversations around me. "Did you see that David Gower cover drive? He never looks like he's trying, it's so effortless." When you hear so many adults gasp in admiration, you subtly absorb new ways of enjoying the cricket on the television screen.

That summer's footage has lodged permanently in my memory. Gower batting without a cap or a helmet, the afternoon sun casting long shadows over the field, and Jim Laker and Tom Graveney trying to find new ways of saying, "He seems to have all the time in the world." When Gower reached yet another hundred with a cover drive, the commentator exclaimed, "I'm not sure if the bowler is clapping the shot or the century."

In artistic terms, this was "High Gower". We didn't know it then, of course, but Gower was exactly halfway through his 14-year England career; he was at the peak of his powers. We knew he was great and we knew he was close to his best. And Gower was not making flawless, inconsequential cameos. He was shaping whole matches with hundreds and double-hundreds. But High Gower, like High Federer, was ruthless as well as beautiful.

Style demands economy as well as grace. In 1985, Gower rarely wasted a movement. Even between balls, he remained in character: his Gray-Nicolls bat resting on one shoulder, blade facing the sky, his grip more open than that of most modern players, the handle settled in his hand as though it was a natural extension of his body.

One of Gower's underestimated qualities was his psychological bravery. He had the guts to keep being himself. Most players spend their careers making increasingly pragmatic compromises. We tend only to hear about the people for whom it works. Steve Waugh, of course, banished the hook shot, and developed an iron-wristed front-footed square cut to replace the classic cover drives of his early days. By the end of his England career, Graham Thorpe rarely allowed himself to use the full array of his attacking shots.

The trend is common across all forms of the game. Maturity is usually accompanied by the reduction of risk: the closing of the bat face, the favouring of the leg side over the off, the narrowing of scoring shots to just a few trusted favourites.

When Gower reached yet another hundred with a cover drive, the commentator exclaimed, "I'm not sure if the bowler is clapping the shot or the century"

If anything, Gower went the other way. He never turned away from risk. He never stopped playing his favourite shots, even when it led to recurrent dismissals. It is too easy to call this a failure of discipline. For batting is not only a question of percentages, it is also a matter of voice. Many batsmen, in the search for scientific progress, lose what makes them special, what makes them unique. Gower never did.

A former team-mate of Gower's once said to me that he "never really got better as an England player". He said it mildly, but it was accompanied by a hand gesture to signify a flat-line. I was tempted to mirror the action, only drawing the flat line significantly higher. If someone averages mid-40s all the way along, the point, surely, is that he has been exceptionally consistent, not disappointingly static.

"Late Gower" also inspired my favourite cricket poem. Gower roused the very best from the editor and poet Alan Ross, himself a romantic, writing in the autumn of his literary career:

Arm confined below shoulder level

As if winged, the slight

Lopsided air of a seabird

Caught in an oilslick. 'Late' Gower,

As of a painting by Monet, a 'serial'

Whose shuffled images delight

Through inconstancy, variety of light.

Giambattista Tiepolo

In his 'Continence of Scipio' created

Just such a head and halo.

For this descendant no confines

Of canvas, but increasing worry lines,

Low gravity of a burglar.

In his 'Continence of Scipio' created

Just such a head and halo.

For this descendant no confines

Of canvas, but increasing worry lines,

Low gravity of a burglar.

Stance, posture, combine

To suggest a feline

Not cerebral intelligence. A hedonist

In his autumn, romance lightly worn,

And now first signs of tristesse ,

Faint strains of a hunting horn.

To suggest a feline

Not cerebral intelligence. A hedonist

In his autumn, romance lightly worn,

And now first signs of tristesse ,

Faint strains of a hunting horn.

Watching a champion in the autumn of his career is a double-edged pleasure. There is joy at the unexpected bonus. But sadness that it surely cannot last for much longer.

That was not the case in 1985. We knew there would be many more days like this, with Gower gliding into cover drives, swivelling on pull shots, and occasionally deigning to sweep - though never touching the ground for long enough with his knee to muddy his pad. Yes, there would be more.

But it was surely never quite so good again.

Former England, Kent and Middlesex batsman Ed Smith's new book, Luck - What It Means and Why It Matters, is out now. His Twitter feed is here