From Sussex with love

With 24 chapters dedicated to various cricketing characters, former first-class stalwart John Barclay offers us a delightful read

Les Smith

26-Oct-2013

Fairfield Books

When I was 11 years old my English teacher instructed me never to use the word "nice" in my writing. He said there is always a more precise and expressive adjective. I've stuck to that for the last 45 years.

Actually, though, "nice" is a nice word when applied to a person. It has attached to it notions of gentleness, kindness, and decency. John Barclay is a nice man, and his niceness permeates his third book, Lost in the Long Grass.

Trout Barclay, as he was known from his middle name Troutbeck, has spent a life in cricket. He was a stalwart county player for Sussex who never quite had the talent or statistics to knock loudly enough on England's door. He was an impressive enough slow-bowling allrounder at Eton for Tony Greig (whom, as this book makes abundantly clear, he idolised) to give him his first-class debut when has 16. For the last five years of his playing career Barclay led Sussex with distinction. Throughout the 27 years since a finger injury forced him to retire, he has remained at the heart and on the beneficent fringes of the English cricket establishment, including presidency of MCC in 2009.

Barclay discusses this last item of recognition with touching humility in the first chapter of Lost in the Long Grass. The book consists of 24 relatively short chapters dedicated, in turn, to characters, mostly players, he has encountered since that debut as a 16-year-old in 1970. He employs this structure as a vehicle not only for character sketches but also for anecdotes that will delight, in particular, readers who, like me, began to be captivated by the game at just the time Barclay's career began. Oh, and there's a dog, but I'll come to him later.

It was Derek Underwood, the subject of the first chapter, who invited Barclay to succeed him as MCC president. Intriguingly, the author writes of "Deadly" Underwood's attitude on the field: "No cursing or swearing, but inwardly he was fiercely competitive, much more so than his countenance would suggest." A personal memory of my own is of being one of a gaggle of schoolboys, autograph books in hand, in the pavilion at The Mote at Maidstone. We all wanted "Deadly" and "Knotty". At the end of a long day in the field against Surrey, our hero told us to form an orderly queue, sat on a chair, lit a cigarette, and signed for us all, with a smile and a word for each.

Chapter three is key. Greig was a hero and mentor to Barclay, even though Greig probably didn't realise it. Greig was himself a relatively young county captain, and Barclay is not so awed as not to point up certain flaws in the young skipper. He was socially impulsive, too keen to fill his side with young players too early.

"If I am brutally honest , he was not a brilliant cricketer, either batsman or bowler, but he made the best possible use of his abilities". Barclay's mother was impressed as well. "Let's be honest, he's like a Greek God".

Another giant of Sussex cricket in Barclay's time was John Snow, and Barclay is acute in his analysis of both the man's character and his talent. Barclay believes Snow was at his best in the late '60s, especially abroad on hard pitches, but notes the success he had on Ray Illingworth's tour of Australia in 1970-71. "Not that Snow was an easy chap. He wasn't. He could be a cold fish, shy, solitary and often ill at ease in public. Moody and awkward he sometimes was".

The pen-and-ink drawings that punctuate the pages evoke a mythical era when cricket was always played in the countryside and, when the weather prevented play, you went fishing

Right in the middle of the book is a chapter devoted to cricket writing, cricket writers he has known, and four in particular. Barclay selects Jim Swanton, John Woodcock (who provides the foreword to this book), Robin Marlar, and Christopher Martin-Jenkins. It's an absorbing chapter. It's also perhaps emblematic that all four are or were from the south-east of England. Indeed, take out Mike Atherton, Geoff Miller, David Lloyd and Ray Illingworth, and this is a distinctly southern book. Then, why shouldn't it be? Barclay was the captain of Sussex.

Barclay is not a distinguished stylist in his writing. The mode of address is more akin to polite conversation and reminiscence in the cricket club bar on a Saturday evening than to the great writers to whom he alludes. But I suspect he's content with that. I am. I've spent many, many hours in cricket club bars reminiscing about glories and failures with friends and opponents far, far less distinguished than those that Barclay writes about.

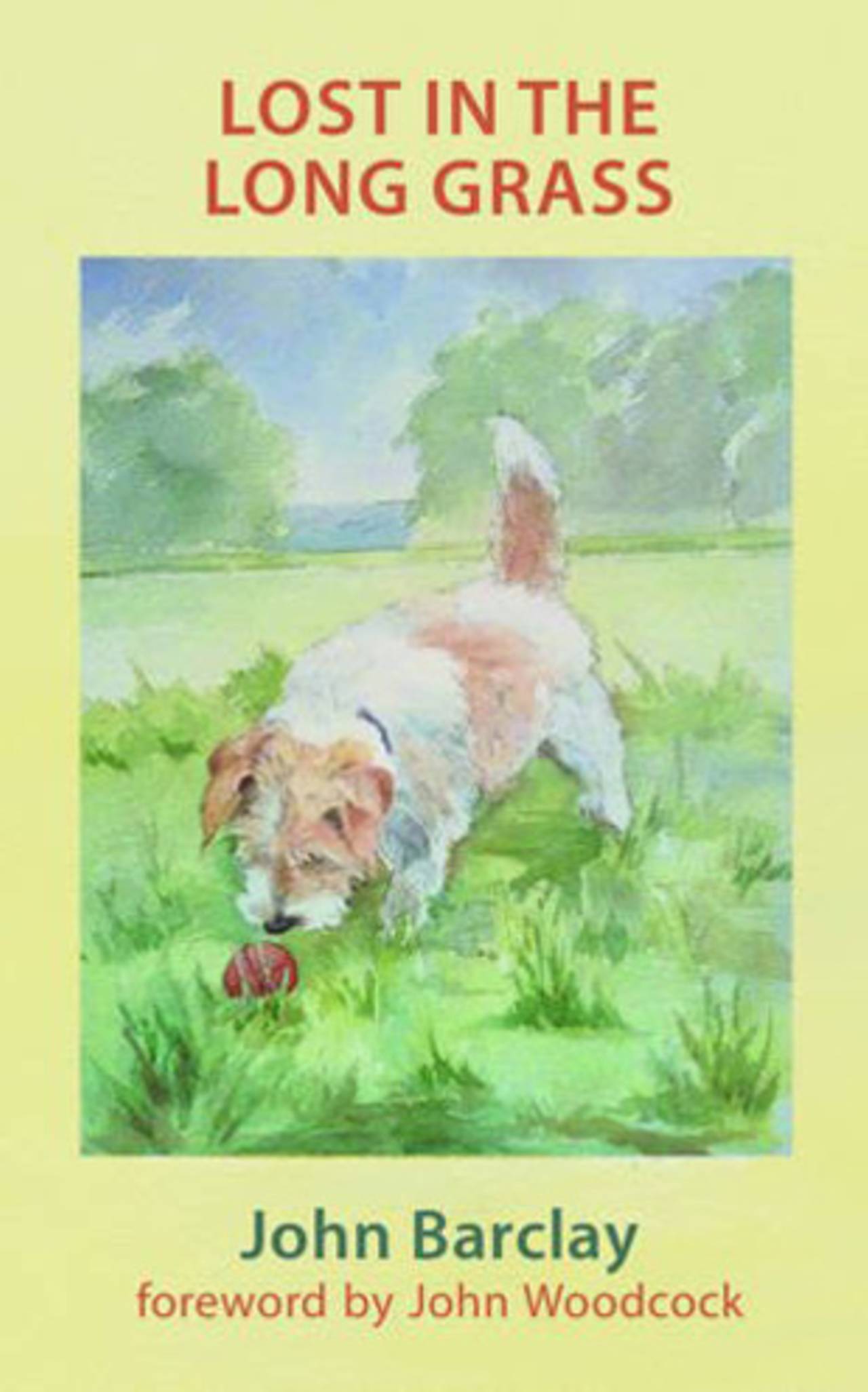

One of the delights of Lost in the Long Grass is the quality of the subtle, discreet illustrations. The cover has a watercolour of a dog retrieving a cricket ball from the long grass. It was painted by the author's wife, Renira Barclay. The pen-and-ink drawings by Susanna Kendall that punctuate the pages throughout the book are equally delightful, evoking no doubt a mythical era when cricket was always played in the countryside and, when the weather prevented play, you went fishing.

Barclay has worked in collaboration with cricket writer Stephen Chalke, who provides succinct pen pictures of each of the author's subjects.

The final chapter is entitled "Robert". Robert is the Barclays' dog. He contributes to what is clearly a contented life at home, except when he collides with the cat Myrtle, but is also a presence at Arundel Castle Cricket Foundation for young cricketers and underprivileged children, where Barclay works.

A nice man.

Lost in the Long Grass

By John Barclay

Fairfield Books

240 pages, £15

By John Barclay

Fairfield Books

240 pages, £15