Bob Fowler - The student prince

Gideon Haigh looks back at Fowler's match in 1910 ... forgotten now, but back then, the talk of the Empire

Gideon Haigh

22-May-2006

Odd Men In - a title shamelessly borrowed from AA Thomson's fantastic book - concerns cricketers who have caught my attention over the years in different ways - personally, historically, technically, stylistically - and about whom I have never previously found a pretext to write

|

|

|

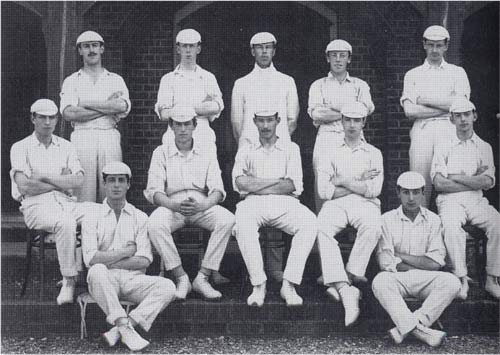

"A more exciting match can hardly ever have been played," decreed The Times, likening its "electric rapidity" to that of the inaugural Ashes Test at the Oval twenty-eight years earlier, and Fowler's performance to that of Fred Spofforth, albeit that "to boys the bowling of Fowler was probably more formidable than Spofforth's to England". Wisden's verdict was even more emphatic: "In the whole history of cricket, there has been nothing more sensational...The struggle...will forever be known as Fowler's match. Never has a school cricketer risen to the occasion in more astonishing fashion".

Eton v Harrow a century ago, after more than a century of exchanges, was at the zenith of its prestige as a fixture. Games drew as many as 20,000 to watch and promenade, transforming the playing field at intervals into a sea of top hats and parasols. As Cricket summed it up in previewing the 1910 match: "Men who have become famous as statesmen, orators, scientists, authors or in some other manner, have done their best for their school at Lord's, and have probably without exception always referred with the pride to the fact that their cricketical skills gained them a place in the XI."

These were, indeed, the sons of the elite, and the future leaders. In the 1910 match were a field-marshal (Harold Alexander), an air vice-marshal (C. H. B. Blount), and an attorney-general (Walter Monckton) in the making, alongside sundry sons of dukes and earls. And it is certainly true in this case that none of the participants ever quite got over the experience. "In the minds even of non-cricketers, the very mention of `Fowler's match' may arouse a faint movement, as of something rare and strange,' said Alexander's biographer Nigel Nicholson in Alex (1973). `To those who took part in it, the memory turns old men into boys."

Nineteen-year-old Bob Fowler was at home in this exalted company. Descended from a Protestant clergyman who had settled in Ireland in the 1760s, he was a son of a professional soldier in Enfield, County Meath. The Anglo-Irish aristocracy at the time would no sooner have schooled their offspring at home than belted out a chorus of Sean South of Garryowen. When he brought the fundamentals of cricket home from his prep school, Mr Hawtrey's in Westgate-on-Sea, he practised by bowling interminably at a chalk mark - with a footman to do the retrieving.

At Eton, Fowler came under the influence of his housemaster, the Middlesex amateur Cyril Wells, who turned him into an off-break bowler of formidable accuracy: his 11 for 79 had almost won the annual fixture for Eton in July 1909. A year later, the challenge was steeper. Only one player other than Fowler carried over from the previous game; Harrow had seven veterans of the rivalry. Their splendoured fixture list had also yielded rather different fortunes: Eton had lost to Free Foresters, Authentics and Butterflies; Harrow were unbeaten, having disposed of Free Foresters, Harlequins, Quidnuncs and the Household Brigade, and very pleased about it in a muscular Christian kind of way. English public schools, of course, could be bleak places for the sport intolerant: the young Nehru found Harrow "a small and restricted place" where boys talked of nothing but cricket. To be fair, though, they had a good deal to be excited about, two Old Harrovians, F. S. Jackson and Archie MacLaren, having led England in the preceding five years.

Harrow began the match on Friday, 8 July, full of purpose, compiling 232 under grey skies on a pitch turning appreciably but slowly. A callow keeper conceded eighteen byes as Fowler and his leg-spinner partner Allan Steel, son of the Test player A. G., shared eight wickets. Nothing suggested that it would not be a match of patient application and minor advantages. But Eton crumbled at once in reply, finishing the day at five for 40: a situation The Times already thought "almost desperate". Fowler's 21 ended up being the only double-figure score in Eton's eventual 67 in 48 overs.

When Steel was caught in the second innings, Eton's score following on had dwindled to five for 65. Spectators began leaving. It was a Saturday. The Gentlemen and Players were playing a tight game at the Oval; perhaps there was more entertainment there. With 100 needed to make Harrow bat again and only the tail remaining, however, Eton rallied. Harrow's fast bowler captain Guy Earle, the only future Test player in the match, unaccountably spelled Alexander, who had already secured five wickets in the match with his legspin, and Fowler found an ally in Donald Wigan, with whom he added 42.

|

|

|

Fowler then teamed up with William Boswell to wipe away the rest of the arrears. In the face of Fowler's controlled hitting - his 64 contained eight fours, a three, ten 2s and nine singles - the fielding grew ragged, and Eton's spectators became as boisterous as Harrow's were solemn. A. B. Stock fell quickly, but the last wicket was prolonged by the two junior aristocrats Hon John Manners and Kenelm Lister-Kaye, who thrashed 50 in a hectic half hour.

There should still have been no question of the result. With Harrow needing only 55 to win, Earle requested the heavy roller to subdue the pitch; Eton faced a challenge of almost exquisite hopelessness. F. S. Ashley-Cooper reported that confidence was still general: "Harrovians, feeling at peace with all men, settled down with a languid air to watch the runs hit off for the loss of perhaps a couple of wickets in half an hour or so."

So quickly did the face of the match change, in fact, that anxiety must have been lurking. Perhaps there was even the seductive sense that all were playing a part in an improbable romance. Any writing about public schools cricket before the First World War demands reference to Sir Henry Newbolt's martial doggerel Vitai Lampada, in which the youthful cry of `Play up! Play up! And play the game!' rallies first a counterattacking cricket team then a beleaguered batallion in a colonial battlescape. It seems sadly apposite here: of the aforementioned boys, Steel, Stock, Manners and Boswell would all be killed on active service in the Great War then barely four years away; likewise the three Harrovians, Geoffrey Hopley, Tom Wilson and Thomas Lancelot Gawain Turnbull, who succumbed in Fowler's first two overs. At the time, though, the elision would not have seemed so crude. Fowler was a soldier's son, destined for Sandhurst. Maybe he invoked Gordon at Khartoum, or Chard and Bromhead at Rorke's Drift; perhaps he enjoined his boys to fight on with the famous words of the expiring colonel at Albuera: "Die hard, 57th, die hard!" Whatever the case, they did fight, fielding tigerishly, catching brilliantly, keeping composedly, preserving that 55 like their vital spark.

Fowler, meanwhile, bowled as he can seldom have bowled. Charles Eyre, an Old Harrovian, felt a grim foreboding at the sight of his first ball: "It looked to break a yard and come off the pitch like a rattlesnake." But conditions were not the determinant. Under such circumstances, slow bowlers can panic, either trying too hard, or expecting the pitch to do all the work. Fowler did neither, simply adjusting his line a little and continuing to vary his pace so that driving became treacherous, and runs nearly unobtainable. Opener Tom Jameson spent forty minutes on 0. Middle order batsman Walter Monckton, equal to the strain of the abdication of Edward VIII twenty-six years later, didn't last that long. "Walter took guard and played his first ball safely," recalled his biographer Lord Birkenhead in The Life of Viscount Monckton of Brenchley (1969). "Then Fowler, by an inspiration of genius, tried him with a slow full-toss, and to the dismay of all his friends and to every Harrow supporter, Walter was clean bowled, and had to make the silent and terrible return to the pavilion."

The most delightful description of Harrow's second innings, however, is an almost unimproveable passage in Lt Col C. P. Foley's Autumn Foliage (1935), which merits quoting at length:

"I was going to spend that Saturday to Monday at Coombe with General Arthur Paget, and, not being in the least anxious to see an overwhelming Harrow victory, I left the ground and called in at White's Club to pick up my bag. Providentially, as it turned out, my hair wanted cutting. Half way through the operation Lord Brackley looked in and said `Harrow have lost four wickets for 21 runs', and a few minutes later, `Harrow have lost six wickets for 21 runs'.

"That was enough. I sprang from my chair with my hair half cut and standing on end, and we rushed together into the street, jumped into a taxi, and said `Lord's! Double fare if you do it in fifteen minutes'. We got there in 14 minutes 21 5/8 seconds (I carry a stop watch), paid the man, and advanced on the pavilion at a pace which is called in the French army le pas gymnastique.

"The shallow steps leading to the pavilion at Lord's form a right angle. Round this angle I sprang three steps at a time, carrying my umbrella at the trail. A dejected Harrovian, wearing a dark blue rosette, and evidently unable to bear the agony of the match any longer, was leaving the pavilion with bowed head. I was swinging my umbrella to give me impetus, and its point caught the unfortunate man in the lower part of his waistcoat, and rebounded from one of its buttons out of my hand and over the side rails of the pavilion.

"The impact was terrific, and the unlucky individual, doubling up, sank like a wounded buffalo on to his knees, without, as far as I recollect, uttering a sound. I sprang over the body without apology, and, shouting out instructions to George Bean, the Sussex pro, who was the gate attendant, to look after my umbrella, dashed into the pavilion and up the many steps to its very summit, where I hoped to find a vacant seat."

No sooner had Foley taken his seat than Fowler bowled Straker to reduce Harrow to eight for 29. Jameson, usually a free scorer and later an amateur squash champion, was also bowled by Fowler after finally scavenging a couple to get off the mark, leaving Harrow twenty-three from victory with a wicket left.

|

|

|

What The Times described as "most pardonable pandemonium" ensued, continuing into the following week, for Eton's VIII also won the Ladies' Challenge Plate at Henley. In celebration, there was a ritual `hoisting', where Fowler, Manners and Boswell, and two rowers were carried quickly, if somewhat uncomfortably, through the college, to the cheers of a throng of past and present Etonians - an event, rather remarkably, considered worthy of a report in the Daily Telegraph full of detail: "The members of Pop assembled on Barnes Pool Bridge at 7.30pm, some attired in flannels and ducks and other wearing top hats."

Fowler's crowded hour, however, was over. A few weeks later he emulated his father by enrolling at Sandhurst, where he won the Sword of Honour the following year and became a cavalryman. With the 17th Lancers, `the death or glory boys' famously bloodied at Balaclava who sported the skull and crossbones on their regimental colours, Captain Fowler lived out the Newboltian vision by winning the Military Cross during the defence of Amiens from Ludendorff's Kaiserschlacht of March 1918. Fowler's cricket henceforward was confined to games for Army and Free Foresters apart from a couple of games for Hampshire in 1924, soon after which he was diagnosed with the leukaemia that killed him the following year, aged 34 - a melancholy case of promise unfulfilled.

In fact, it is doubtful Fowler mourned missed sporting opportunities. Testimonies to him suggest a young man consumed by martial and filial responsibilities: "His simplicity, straightforwardness, courage and pertinacity were as noticeable in afterlife as they had been at school," wrote his obituarist in The Chronicle at Eton. What survives of him is not, however, a career of brave soldiering: his enduring fame lay not in the corner of a foreign field, but in the middle of a local one, where he became the schoolboy cricketer in excelsis. What good came of it at last? As Old Kaspar answered Peterkin: "That I cannot tell," said he, "But `twas a famous victory."

Gideon Haigh is a cricket historian and writer