'Palairet had style. It stood out a mile'

In the first of a new series, Paul Edwards takes us back to the Golden Age and an unmistakable Somerset stylist

Paul Edwards

Apr 16, 2020, 11:01 AM

Getty Images

In the first of a new series inspired by AA Thomson and Gideon Haigh's Odd Men In, Paul Edwards takes us back to the Golden Age and an unmistakable Somerset stylist...

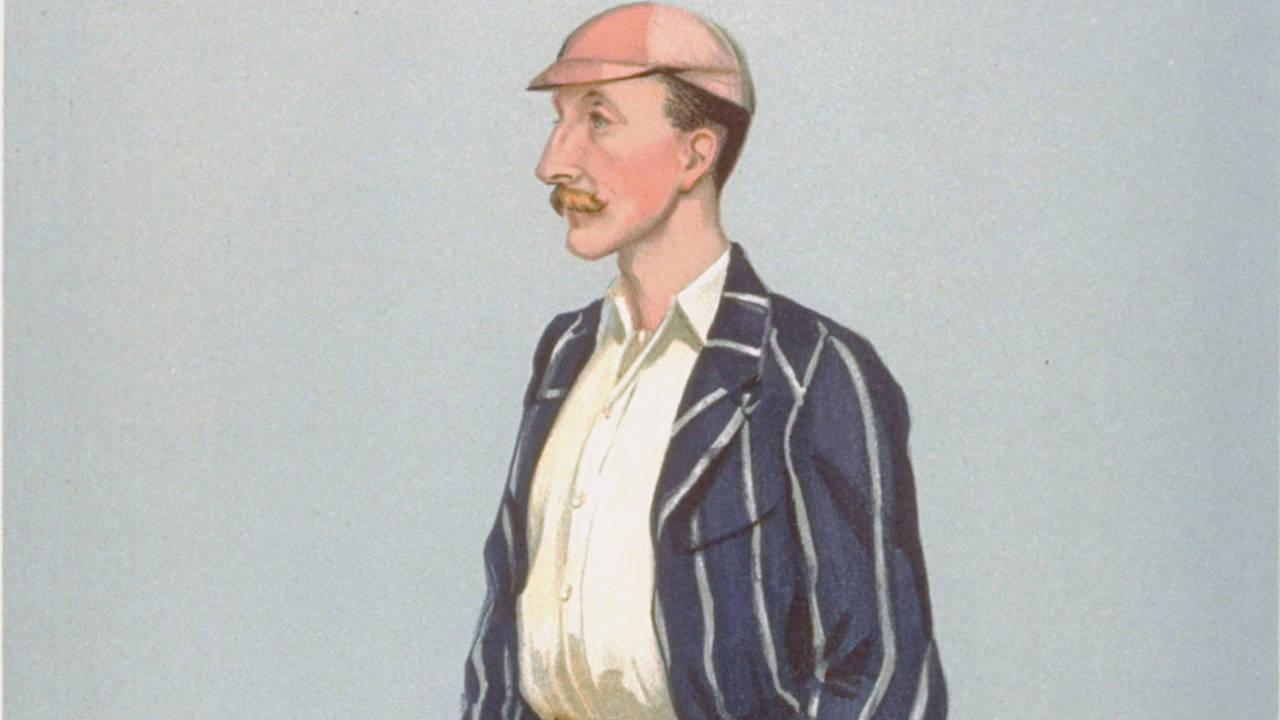

The pose, if pose there ever was, suggests a studied casualness. The batsman still has his pads on and one leg is a little in front of the other, indicating the balanced ease so characteristic of his cricket. The blazer recalls its owner's four summers in The Parks and the Harlequin cap is his favourite headgear. Instead of an orthodox belt he has a sash tied round his slim waist and its colours may be those of MCC, another club for whom he played. The only article of clothing missing from his usual garb is the white linen kerchief he is wearing around his neck in the only film of him, which was shot during Lancashire's game against Somerset at Old Trafford in 1901, when he is seen walking from the field and talking to his chum, Archie MacLaren. Such friends nicknamed him "Coo" or, occasionally, "Stork"; the professionals called him Mr Palairet and perhaps one or two other things behind his back.

The luxuriant moustache might owe something to Trumper (not Victor, you understand, but Geo F, the gentleman barbers of Curzon Street, Mayfair). The hands are thrust deep in the flannels' pockets; the gesture of a man who has rarely needed to ask anyone's permission to do so. Our tall cricketer seems to be watching something - it might even be the game - yet he is doing so with a superior, perhaps slightly arrogant, eye. In any event this Vanity Fair cartoon helps to explain why the work of its artist, Sir Leslie Ward ("Spy"), is still collected. For it certainly captures the essence of Lionel Charles Hamilton Palairet's character. And so, naturally, it has style.

Virtually everyone who saw Palairet play cricket commented on the beauty of his batting. Harry Altham deserves some sort of posthumous hosanna for managing to do so in A History of Cricket without mentioning the word "style", yet over half a century after he first saw Palairet bat at Taunton the old boy stood by the rapture he first felt as a child at the turn of the century.

"Of Lionel Palairet I confess that I cannot write with any pretence to judicial impartiality… of all the great batsmen I have been privileged to watch and admire, none has given me quite the sense of confident and ecstatic elation as Palairet in those days. Whenever I came to the ground he made 50, often 100; once I followed him to the Oval, and was rewarded with an innings of 112 against Lockwood and Richardson at their best, for which even the sternest critics were beggared for epithets. A perfect stance, an absolutely orthodox method, power in driving that few have equalled and withal, a classic grace and poise, unruffled even in adversity. Even now I can recapture something of a thrill when I recall that gorgeous off-drive, with a flight like a good cleek-shot, swimming over the low white railing of the Taunton ground. From the day on which I first saw it, his Harlequin cap took on the colour of all earthly ambition."

His stance was perfect, and motionless. Everything about him epitomised grace; there was never a superfluous movementDavid Foot on Lionel Palairet

It seems cheap to ruin a good tale but Bill Lockwood wasn't actually playing in that 1898 game, which Surrey won by nine wickets, but Altham's mention of a cleek, an early version of the one-iron, reminds one that Palairet was a multi-talented sportsman who ran the three miles for Oxford University, played football for Corinthians and was celebrated in his later life for his contributions to golf in Devon. The short profile attached to the Vanity Fair cartoon reflects its Edwardian age by mentioning that he was also "a good shot and a capital billiard player".

Palairet's host of other interests place him ever more firmly in cricket's Golden Age, when amateurs often had to balance any commitment to the game against their other enthusiasms and even - dash it all - their need to make a living. In his case this latter requirement involved him first in directing the Newton Electrical Works in Taunton and then by working as a land agent for the Earl of Devon, a job he later combined with being Secretary of the Taunton Vale Foxhounds. His sporting prowess and that annoying requirement for paid employment also allow him to be bracketed with CB Fry, who was at both Repton and Oxford at the same time as Palairet and who would write about his contemporary in The Book of Cricket and the far more notable Great Batsmen - Their Methods at a Glance. The latter book is famous for capturing the dynamic power and grace of Victor Trumper but George Beldam's photographs achieve a similar feat with Palairet's lesser talent.

And so, perhaps inevitably, we return to reality and, eventually, its pictorial representation. Palairet's statistics were respectable but they hardly fork lightning. In 267 first-class matches over 19 seasons he scored 15,777 runs at an average of 33.63 - though it should be remembered that many innings were played on pitches which would attract ECB penalties today. He scored 27 centuries, five of them against Yorkshire and another four against Surrey, the most powerful counties in the land at that time. His 292 against Hampshire in 1896 remained Somerset's highest individual score until Harold Gimblett beat it in 1948, and his 346-run first-wicket stand with Herbert Hewett against Yorkshire at Taunton in 1892 remains his county's second-highest partnership in first-class cricket. He played only two Test matches, both in 1902, but they are ranked among the great ones. In the first, at Old Trafford, Victor Trumper made 104 and Australia won by three runs; in the second at The Oval, Gilbert Jessop's 75-minute century set up England's one-wicket victory. Palairet's aggregate from four innings was 49 runs.

All but one of Palairet's hundreds were scored in the 13 seasons from 1891, Somerset's first in the County Championship, until 1904; the other came against Kent in 1907. That was the year he agreed to captain a weak side only to resign when his team finished the campaign with only Northamptonshire and Derbyshire below them. Like many skippers who lead teams for one season, he fell into the trap of staying on a year too long. "This season is the most disappointing I have had to face in my life. Throughout the season this team has had no fighting spirit, there is a distinct lack of ability and the team is ageing with no talent coming through to compete at a first-class level," he moaned in the Taunton Gazette that autumn. Historians have interpreted events differently. "Colleagues found Palairet somewhat aloof, a reserved fellow, incapable of inspiring affection, save among his closest friends," wrote Peter Roebuck.

Getty Images

Yet to Altham and almost everyone else who saw their hero bat none of this mattered. Jessop told of the game against Somerset when a young Gloucestershire amateur tried to stop one of Palairet's powerful off-drives and got a ball in the face for his pains when it ricocheted off his hand. The same thing happened to the substitute who replaced the naïve freshman. There is little suggestion of that power in the posed shots taken by Chaffin for The Book of Cricket. But there an abundance of graceful ease in Beldam's two photographs of Palairet's off-drive in Great Batsmen. That impression supplies a slight but important corrective to Patrick Morrah's cautionary note that "the peculiar distinction of his style can only be taken on trust".

The matter is further clarified by David Foot, who spoke to anyone he could find who had seen Palairet in his pomp. Typically, Foot offers a daring modern comparison, too: "Perhaps his manner wasn't flamboyant enough [to get more than two England caps] - he got his runs with the minimum of extrovert flourish and had no quaint mannerisms to amuse or intrigue the spectators. His stance was perfect, and motionless. Everything about him epitomised grace; there was never a superfluous movement. One obvious point of comparison with Viv Richards, in fact, was his obvious stillness at the crease. The back lift, the quiet and assertive advance of the front foot, the overall co-ordination were near perfection…."

Foot eventually joins the ranks of writers who think Palairet the most stylish English batsman ever to have played the game. Golden Age contemporaries like Fry, Plum Warner and Ranji were also effusive in their praise. Yes, their beau ideal scored most of his runs on the posh side; he might also have been a snob and one of RC Robertson-Glasgow's one-way critics. His Presidency of Somerset in 1929 was remembered for his claim that batting in that era of Walter Hammond and Frank Woolley was marked by a "siege mentality".

But none of that counted for much to the boys at Taunton, who realised some 60 years before Sammy Cahn that you've either got or you haven't got style. And Lionel Palairet had it. It stood out a mile. Everybody said so.

For more Odd Men In stories, click here

Paul Edwards is a freelance cricket writer. He has written for the Times, ESPNcricinfo, Wisden, Southport Visiter and other publications