The Blaze of Glory XI

Part one of the Official Confectionery Stall team who exited to applause

Andy Zaltzman

25-Feb-2013

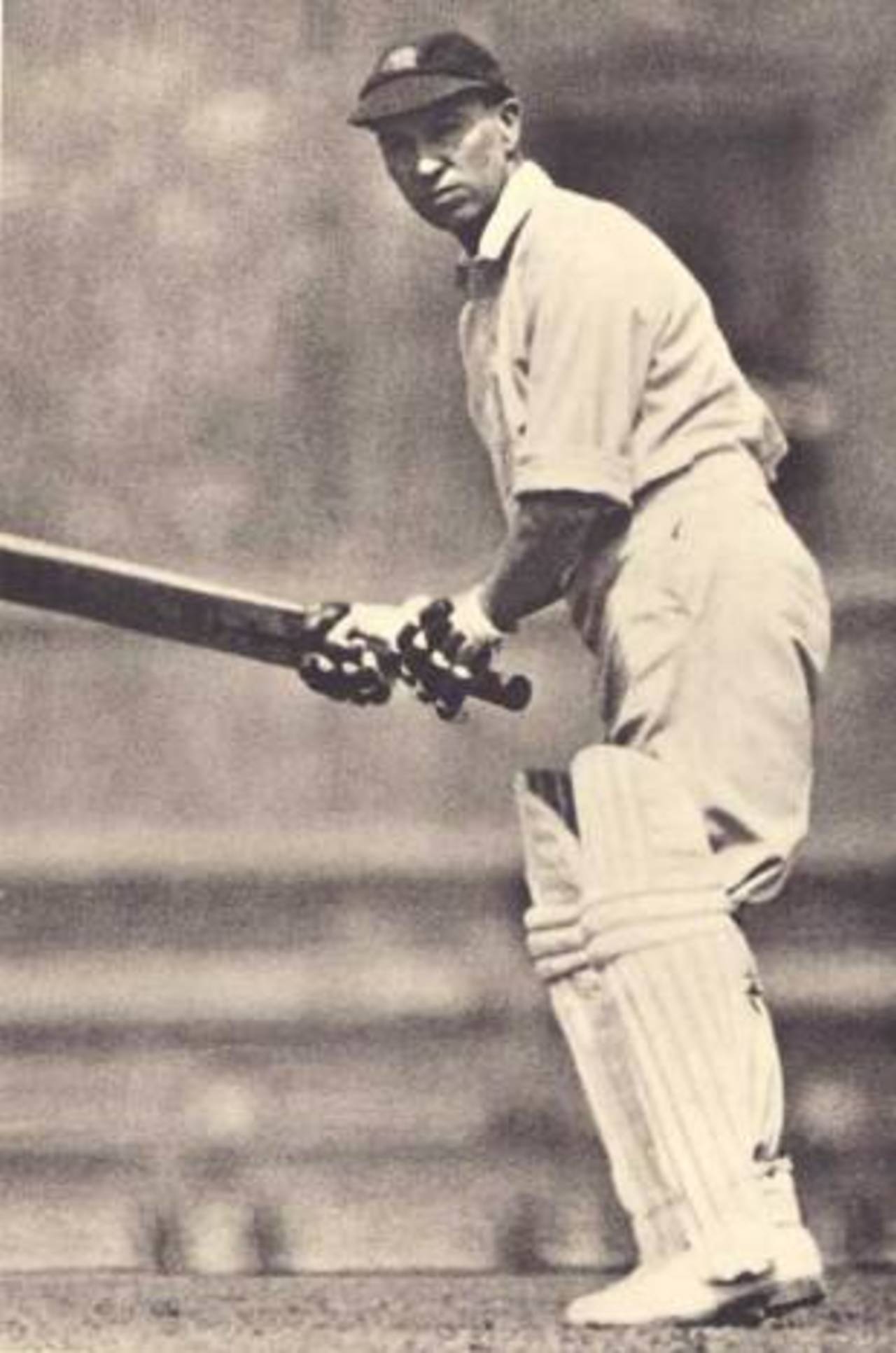

Andy Sandham: would have been a goner if they had Twitter in his time • ESPNcricinfo Ltd

Further to my reflections on the dimming of great players’ careers a couple of blogs ago, and the struggles of India’s once-golden-but-now-greying batting generation, here, by way of happy contrast, is part one of the Official Confectionery Stall Going Out in a Blaze Of Glory Test XI.

The selection committee (me; my two children, who regrettably missed the selection meeting due to it being well past their bedtimes; and my wife, who abstained in protest at the increasingly domineering influence of Twenty20 on global cricket; and the ghost of former England skipper Douglas Jardine [via ouija board]) established various criteria for this deeply prestigious XI:

● Players should have had Test careers that were not an unremitting blaze of glory. Murali left the Test scene by spinning Sri Lanka to victory on his home turf and taking his 800th wicket with his final ball. There have been few more spectacular partings from any scene since Laika the Soviet Cosmodog’s last ever walkies saw her chasing her final stick in outer space. Warne and McGrath helped Australia to a cleansing, vengeance-assisted 5-0 Ashes clouting of England, and exited to universal baggy green worship. Bradman, despite his final-innings duck, averaged 105 in his 15 post-war Tests, and in his penultimate innings had smashed 173 not out to chase down a record 404 in less than a day to win the fourth Test. But these men knew little but glory for most of their careers. And, in fact, all four of those legends saw their Test averages worsen (relatively) in their final series. The panel wanted players whose career-ending triumphs came, if not totally unexpectedly, then certainly in contrast to their overall career performances.

● The players’ careers should have been long enough for the blaze of parting glory to stand out from a more general smoulder of adequacy. Barry Richards came into and departed from Test cricket in a veritable conflagration of magnificence in just seven innings, the last a dazzling 126 to help seal a South African whitewash of Australia. In the same game, Mike Procter had match figures of 9 for 103, to finish with 26 wickets at 13 in his final series. But it was the final series of two, and the other one had been almost equally stellar. They have no place in this team.

● The committee resisted the temptation to pick Jason Gillespie as a specialist batsman. Double-centuries against Bangladesh do not count as blazes of glory, any more than me slotting an ice-cool penalty past my three-year-old son in the Zaltzgarden last weekend warranted the celebration that it prompted.

● The committee, under the terms of the UN Convention on Sporting Selection Committees, reserved the right to select players on an unexplained personal whim.

Here are the top four batsmen:

1. Andrew Sandham (England, blazed out gloriously in 1929-30)

Sandham had failed as a Test batsman in the early 1920s, with a solitary half-century in ten sporadic Tests, but, aged 39, with England’s resources stretched, he was selected for the tour of West Indies in 1929-30. It was an under-strength team. Not only did Hobbs, Sutcliffe and Hammond all take the winter off, but England were simultaneously playing another Test series in New Zealand. And to think that people complain about the hectic international schedule and player rotation devaluing international caps now.

Surrey stalwart Sandham scored 152 and 51 in the first Test, but followed up with four single-figure scores in the next two, and thanked his lucky stars that technology’s development of the internet message board remained a solid 70 or so years in the future, and that 1930 cricket fans would merely tut quietly at their newspapers in a few days’ time, whilst smoking a pipe, rather than instantly logging on, impugning Sandham’s parentage, and calling for Lancashire’s Frank Watson to be given a go instead, after a promising season in the County Championship.

Sandham walked to the crease in the final Test with a Test average of 24 after 13 Tests. He walked away from it at the end of the match with a rather broader grin, and an average of 38, after scoring 325 and 50. His efforts did not result in a valedictory victory, however. The supposedly timeless game was called off as a draw to enable England to catch the boat home.

Arguably, with a handy first-innings lead of 563, captain Freddie Calthorpe could have risked enforcing the follow-on, but erred on side of caution, to the surprise of many, not least of caution itself, which in the circumstances was settling down for a spot of sunbathing and not expecting to be disturbed. Rain, the transatlantic shipping schedule, and the genius of George Headley saved West Indies, and with Hobbs and Sutcliffe restored for the summer’s Ashes, Sandham never played Test cricket again.

(Footnote: Sandham was born in Streatham, where I now live, so, according to the traditions of selectorial privilege applied intermittently throughout cricket history, I’m picking him.)

2. Bill Ponsford (Baggy Greenland, nailed his dismount like a cricketing Comaneci in 1934)

Ponsford, a domestic run-scoring leviathan and the only man to score two first-class quadruple centuries before Brian Lara, had had a largely anticlimactic Test career after a debut century in 1924-25. By the time of the penultimate Ashes Test of 1934, he had passed 50 only twice in 11 Tests over three and a half years, and scored one Ashes century in four-and-a-half series.

Then, springing to life like a dormant Vesuvius annoyed by some noisy Pompeian teenagers holding an unnecessarily loud party, he hit 181 in Leeds in an elephantine partnership with Bradman, before, in the decisive Ashes-winning Oval Test, he clonked England for 266, adding 451 in five hours in another woolly mammoth of a stand with the Don.

A strong England attack (Bowes, Allen, Verity) was surgically dismembered like a psychotic child’s pet centipede, Australia won by a Bodyline-salving margin of 562 runs, and despite a final innings of just 22, Ponsford in his final two Tests had catapulted his career average up from 40 to 48 ‒ still far below his first-class figure of 65, but much more befitting a man who had been the run-scoring John the Baptist to Bradman’s statistical Jesus.

3. Vijay Merchant (India, went out with a bang in 1951-52) (having previously gone out with a bang in 1946)

Merchant was another first-class phenomenon with a relatively moderate Test record (albeit from very few matches spanning several years and a World War), until back-to-back hundreds in his final two Test innings ratcheted his average up from 36 to 47.

“Back-to-back” might be something of a terminological stretch. Those backs were further apart than those of a divorcing couple ignoring each other on the top deck of a cruise ship on the final day of a make-or-break holiday. (That simile has been referred to the third umpire.) (Rightly so.) (Red light.) (Apologies.) Merchant hit 128 in the rain-sogged final Test at The Oval in 1946, then missed India’s next two series through illness. It seemed his international career might be over, but he returned to score 154 in Delhi in the first Test of India’s 1951-52 series against England. Before promptly injuring himself fielding and never playing Test cricket again.

Given that Merchant’s final two innings were played more than five years apart, he could be argued to have bowed out of Test cricket in a blaze of century-scoring glory not once but twice. Perhaps even three times, if you consider that his pre-war Test career had ended in 1936 with scores of 114, 52 and 48, before a ten-year hiatus.

Merchant edges out Australia’s Charlie Macartney, who after averaging 26 before the First World War (including just 18 in his first 13 Tests), was so reassured by the Treaty of Versailles that he spanked six hundreds in his 14 Tests from 1920-21 to 1926, averaging almost 70, including three in successive innings in his final series (one of them a century before lunch on the first day at Leeds). However, he was out for 25 and 16 in his final Test and Australia lost the Ashes, so Macartney misses out. There is no place for sentiment in cricket selection. He needs to go away, get back in the nets, and work on his final-Test form.

(Footnote: Merchant was ever-present for India for 13 years from 1933 to 1946. In which time he represented India in nine matches. His entire ten-Test career lasted 17 years 11 months. After 17 years 11 months of his career, Tendulkar had played for India 543 times.)

4. Nasser Hussain (England, unexpectedly Knievelled himself into retirement in 2004)

Hussain had stepped down as England captain in 2003 after a four-year spell in which he led England to some of its finest modern victories and competitiveness against all-comers. Except Australia, who still routinely pulverised Hussain’s team to a barely recognisable mush. As a batsman, he continued to contribute useful half-centuries of often painful caution, but had averaged under 30 and scored at barely two runs per over during England’s last three series.

Vaughan’s new England was emerging. But for the first Test of the 2004 summer, against New Zealand, it emerged without Vaughan. The injured skipper was replaced by debutant Andrew Strauss, who promptly scored a silken 100. Hussain’s slow career fade seemed to be entering its final spluttering throes. His career’s friends and admirers were gathered round its bedside, vainly hoping for signs of life, fondly reminiscing about his 207 against Warne, McGrath, Kasprowicz and Gillespie at Edgbaston in 1997, and waiting for the ECB’s in-house priest to do the honours.

Then, in the second innings, with England chasing a tricky 282 to win, the former captain joined the future captain at 35 for 2. He poked, ground and plinked his way to 50 off 158 balls, in the course of which he treated himself to running Strauss out 17 short of a historic second debut hundred.

England were edging slowly towards victory when Hussain cut loose from years of dogged restraint and clobbered 53 more off his final 46 balls as a professional cricketer. He reached his century with successive boundaries, before winning the game with a final thwack through the covers. England’s long-held respect for Hussain mutated in minutes to baying adulation, he marched off the field in personal and collective triumph, at the Home of Cricket, and retired instantaneously from the sport. A fighting career had ended in flamboyance. It was as if at the end of Saving Private Ryan, the war-ravaged Tom Hanks had suddenly sailed off into the sunset on a luxury yacht with a bikini-clad beauty like a particularly frisky James Bond.

Next time: numbers 5 to 8. Could Geraint Jones’ pair at Perth in 2006-07 be enough to snare him the wicketkeeper’s spot? No. No it could not.

Andy Zaltzman is a stand-up comedian, a regular on the BBC Radio 4, and a writer