Greetings from New York City, where non-cricketous work has taken me temporarily to the place where

Donald Bradman met Babe Ruth, and, one hopes, tried to convince the legendary Yankees slugger that if he did not hit the ball in the air so often, his innings might last rather longer. In fact, it is entirely possible that Donald Bradman ate a bagel, or put on a gorilla suit and tried to climb up the outside of the Empire State Building, or said “You talkin’ to me?” whilst looking at himself in a mirror, within a just few blocks of where I am writing this now. I can feel the cricketing history in the air.

It is also possible that, given that he was in New York

during a honeymoon which consisted of a four-month cricket tour, that the new Mrs Bradman at some point, perhaps on the sidewalk right below my window, pulled the Don aside and said: “Next time you go on a honeymoon, can I suggest you do so without 12 other men in tow? It is just not the more romantic way to make a girl feel special. And stop looking at the Statue Of Liberty like that. I know she’s hot, but I AM YOUR WIFE. How was the game, darling?”

Welcome to Part 2 of the the Official Confectionery Stall Going Out In A Blaze Of Glory Test XI. Since

Part 1 was released, Rahul Dravid has retired from international cricket. Had he had done so after last summer’s series in England, he would have strolled into this team, despite India’s total failure as a team, after one of the finest sustained displays of the craft of batsmanship seen in recent years.

Instead, a largely fruitless tour of Australia, and another sadly thorough walloping for his country, means that he has departed the Test scene with the same number of runs in his final Test as mustered batting legends RP de Groen and Franklyn Rose, and by joining Richard Blakey and Adrian Griffith as players who have exited Test cricket as part of a whitewashed team (plus, in fairness, several players of elevated cricketing stature) (and, potentially, the entire current England XI if they all decide to quit cricket and join a religious commune). It was an exit ill-befitting one of the Test game’s finest players, after 16 years of silk and steel in his nation’s cause, the undisputed Michelangelo Of The Forward Defensive.

Here then is Part 2 of the XI – The Middle Order.

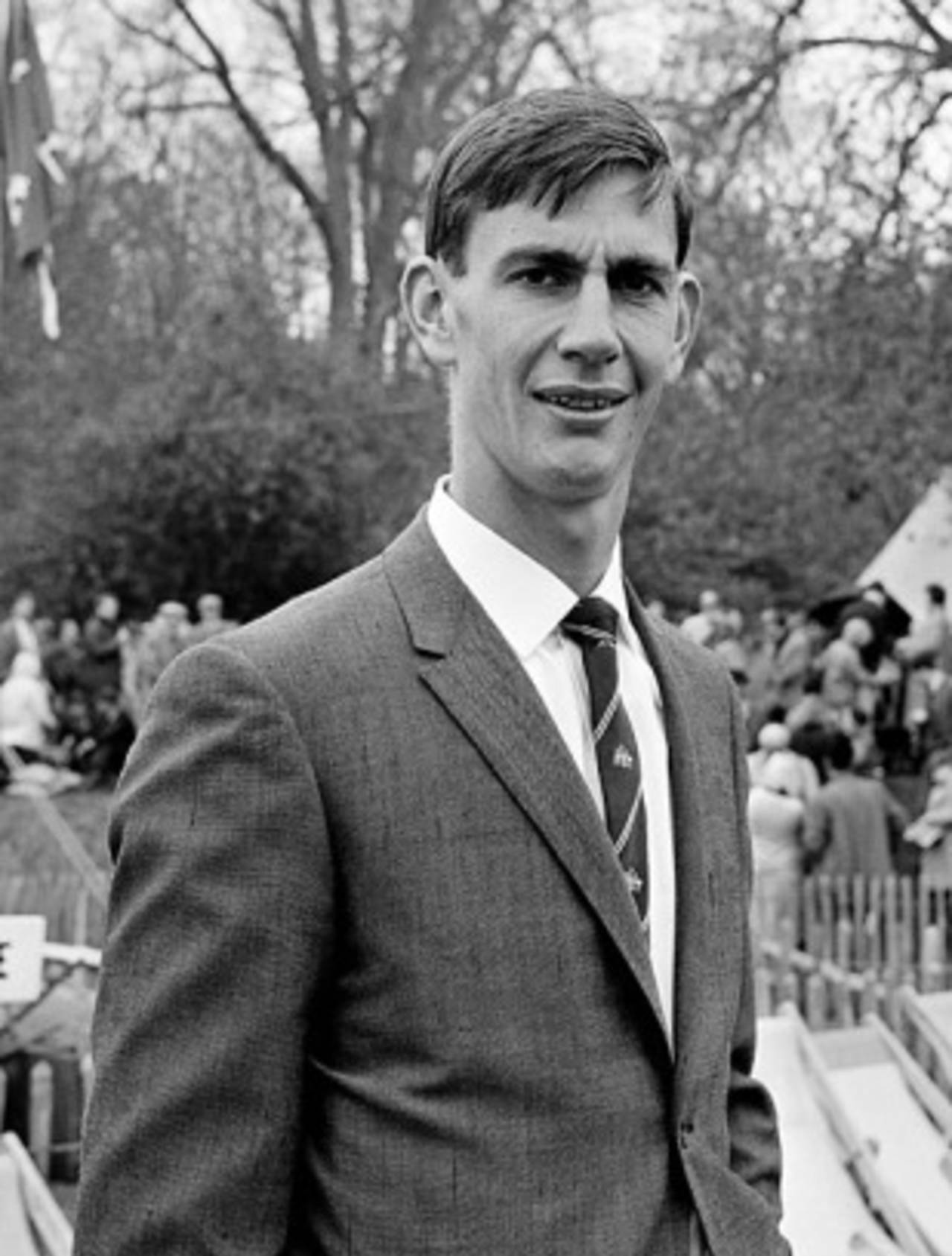

5. Seymour Nurse (West Indies, rode the fiery chariot of retirement across the statistical skies in 1968-69)

The Test cricketer whose name sounds most like an entry on the to-do list of a philandering doctor, Seymour Nurse holds the record for the highest score in a player’s final Test innings – 258

against New Zealand in 1968-69. He scored it out of a West Indies total of 417 all out (the

highest proportion of a team’s score by a double-centurion in a completed Test innings, as I’m sure he never tires of telling his friends, family and assorted passers-by).

Nurse had scored three Test hundreds in his first 48 innings for West Indies, over eight years. His gargantuan valedictory masterpiece gave him his third century in his final six Test innings during four presumably highly enjoyable weeks early in 1969, a spell which bumped his career average up from a Craig-McMillan-esque 38.8 to a Boycottian, Kanhai-ic, matching-Adam-Gilchrist-to-two-decimal-places 47.60.

Nurse edges out Australia’s Ian Redpath, who, after accumulating just five tons in his first 62 Tests over 12 years, then plundered three more in his final four Tests and five weeks as a Test cricketer. His final two Tests brought scores of 103, 65, 101 and 70 as Greg Chappell’s team completed a 5-1 cauterisation of the West Indies in 1975-76. Redpath then departed the scene giggling at having played a major role in riling Clive Lloyd’s team so much that they promptly unleashed history’s most fearsome pace battery upon the cricketing world and became all-but invincible for a decade and a half, whilst Redpath withdrew to a safe distance and enjoyed a happy retirement.

6 & captain: FS Jackson (England, blasted out of the Testosphere in 1905 by skippering England to Ashes glory whilst topping the batting and bowling averages)

Colonel The Honourable Sir Francis Stanley Jackson, P.C., G.C.I.E., not only possessed one of the most impressive collections of titles ever acquired by a Test cricketer, but also frequently boasts to his friends in the celestial pavilion that, in 1905, he laid on the finest ever all-round performance by a captain on in his valedictory Test series.

In the first Test, Jackson took 5 for 52 to bowl England back into contention after a poor first innings, then scored 82 not out as England marched to victory; in the second game, he dismantled a stellar baggy-green top order by dismissing Trumper, Hill, Noble and Armstrong. He chipped in with a few useful wickets in the remainder of the series (ending with 13 wickets at 15), but it was with the bat that he then destroyed Australia.

He scored 144 not out in a first innings of 301 all out at Headingley (no one else passed 35), 113 to set up England’s series-clinching innings win in the fourth Test, and 76 and 31 at the Oval to finish with 492 runs in the series at an average of 70, then the highest series aggregate by an England batsman. It remained highest total by any player in a series in England until Herbert Sutcliffe scored 513 against South Africa in 1929 (only to be narrowly pipped at the post the following summer by Bradman, who scored a useful 974 in 7 innings).

As captain, he also formulated the brilliant tactic of winning all five tosses in the series. A strategic masterstroke.

7 & wicket-keeper: Denis Lindsay (South Africa, bowed out in the final Test of the 4-0 clubbing of Australia of 1969-70, alongside the rest of a dazzling team (except tweakster John Traicos, who was merely biding his time before returning as a Test player 22 years later for Zimbabwe) (and whose closest family would probably not argue that he was among the more dazzling products of that South African side) (with all due respect to an extremely reliable offspinner) (but seldom has he been described as “the Graeme Pollock of offbreaks”, or “the bowler Mike Procter could have been if he’d slowed down and tried to tweak it a bit”, or “like Barry Richards trapped in a slow bowler’s body”)

Selecting the gloveman for this XI is a tough business. Only one wicketkeeper has scored a hundred in his final Test ‒ England’s Henry Wood, a fine player no doubt, but one of whom few England fans have tattoos on their shoulders these days. Wood tonked his only first-class hundred in his final Test, in 1891-92 for a barely-representative England (two of the whose team had recently played for Australia, presaging a glorious long-held tradition of open-minded acceptance of foreign-reared players into the English game) against an extremely weak South Africa, one of whose number had recently played for England (thankfully, this deeply regrettable late 19th-century policy of South Africa farming English cricketers to compensate for their own shortage of home-grown talent petered out soon afterwards).

Lindsay gets the selectorial nod as a representative of the magnificent South African team that could have gone on to prove itself one of the greatest of all time, had it not been for their government’s predilection for institutionalised state racism.

In his final Test, Lindsay, who had struggled in his early Test series before exploding to prominence with 600 runs including three centuries against Australia in 1966-67, scored a patient 43 in South Africa’s first innings, followed by three catches to help his team to a 99-run lead. South Africa, through farewell centuries by Richards and Lee Irvine, then took total control, and Lindsay rammed home their advantage by hammering a 54-ball 60. He took four more catches in South Africa’s final Test action for 22 years, the most dismissals by a wicketkeeper in the fourth innings of his final Test. South Africa disappeared from the Test game for more than two decades, and Australia breathed an extremely baggy and green sigh of relief.

Next week: the bowlers. Warning: will not feature Ian Salisbury or RP Singh.

Andy Zaltzman is a stand-up comedian, a regular on the BBC Radio 4, and a writer