The cries of a cricket pro

Fred Root toiled his way through 23 years and yet got little in return

Gideon Haigh

17-Jan-2006

Odd Men In - a title shamelessly borrowed from AA Thomson's fantastic book - concerns cricketers who have caught my attention over the years in different ways - personally, historically, technically, stylistically - and about whom I have never previously found a pretext to write

|

|

|

One day at Worcester 80 years ago, when the home team were playing Glamorgan, the visitors' opening pair, Arnold Dyson and Eddie Bates, were involved in a mid-pitch collision that left both prostrate on the pitch as the ball was returned to bowler Fred Root.

Root paused, then generously chose not to break the non-striker's stumps: the batsmen seemed quite badly injured. "Break the wicket, Fred, break the wicket!" shouted a keen amateur teammate. Root was annoyed: "If you want to run him out, here's the ball; you come and do it." The amateur explained hastily: "Oh, I'm an amateur. I can't do such a thing."

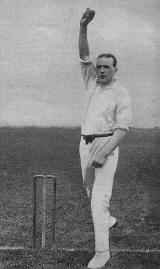

Root, as he recalled it, was irked - as, in a 23-year career bowling inswing for Leicestershire, Derbyshire and Worcestershire, he often was by just such hypocrisies. English cricket between the wars is generally regarded as a period of prelapsarian innocence in which cricket was a game and everyone knew their place. Jack Williams writes in Cricket And England (1999): `Assumptions about cricket being an expression of English morality were not restricted to the inter-war period, but they were probably no stronger at any other time.' Root, with his earthy name, burly physique and open mien, looks like one of those cheerful toilers that were the backbone of the county-cricket economy. Except as his fascinating autobiography A Cricket Pro's Lot (1937) reveals, he wasn't.

Root, the son of Leicestershire's groundsman, was not to be deflected from a boyhood ambition to become a cricket pro. As a 15-year-old, he visited his vicar in search of a testimonial. The vicar asked who it was for. "Please sir, to Mr Robson, the secretary of Leicestershire Cricket Club," explained Root. "And I am going to be a cricketer." The clergyman harrumphed: "I couldn't possibly allow it to be used for the purpose you propose." No matter - there were other vicars. When Root was shot in the chest as a dispatch rider in 1916 and an army doctor told him he was to be discharged but could not realistically expect to play cricket again; he arranged a contract in the Bradford League from his hospital bed.

Root's book is unwaveringly loyal to those of his vocation. Of the best dozen batsmen and bowlers he chooses from his career, 11 are professionals. His hero was selfless Dick Pearson, who always went without wages if money was short and "thought it an honour to wait"; he delighted in `Nudger' Needham, who wore his street clothes beneath his flannels so he could hasten to catch the same train every night from the station. He also admired those amateurs who played like professionals, like Johnny Douglas, whom he once heard coaching a young left-arm spinner: "Joe, if you bowl that sort of tripe again I'll punch your head."

There are no statistics in A Cricket Pro's Lot: Root deprecated them as a measure of merit. Instead, there is a calculus of his productivity per pound of wages. Root explains that he budgeted 1500 overs a season for 150 wickets, and 47 innings for between 800 and 1000 runs. For this, he complained, he could expect just 300 pounds, less hotels for away games, taxis, insurance and incidentals: he had even to pay for his own rubdowns. "It is popularly supposed that there is quite a lot of money in first-class cricket," wrote Root. "If there is, I have not found it. It is the worst paid of all the professional games."

The advice section of A Cricket Pro's Lot is occupational and not inspirational, aimed not at producing champions but at assisting the jobbing cricketer with a lifetime of tradesman's tricks: one learns to use talcum powder for chafing, methylated spirits for skinned fingers, and not to forget an extra pair of socks for support. Find your limits, is the message; don't let them find you. Don't try bowling fast: "Not one in a hundred youths can bowl really fast." "Don't try moving it too much: "The most dangerous ball is the one that `moves' a little." "Don't waste energy as you get older," "A cricketer is as old as he fields." And don't forget to contemplate your mortality: "The professional cricketer's boom years are few...When age takes its toll, it needs a man with a very strong will to adapt himself to the humdrum of ordinary life...and days are long and prosaically uneventful. Many of the cricket heroes of the past are getting what consolation they can out of their memories - and an unskilled job of work at a mere pittance of a wage."

Early in his career, Root complained to "a well-known official holding high office at Lord's" about being required to do so much hackwork in the nets before games. The official upbraided him: "I am surprised at you, Root. You are lucky to be playing in the match at all. Please realise that professional bowlers are nothing more or less than the hired labourers of the game." Nothing in A Cricket Pro's Lot is described with such relish as him getting the better of such stuffed shirts. Root describes, for instance, how he persuaded the poor-mouthing Worcestershire committee to guarantee him a benefit of £500. The club secretary pleaded: "If we had any money, Fred, we would make it £1000, but, knowing as we do, how you so richly deserve all we can possibly afford, shall we agree on £250?" Root simply fished out the offer of a Lancashire League contract worth £600 that he had just received; the request was granted.

Root's particular grievance, however, was not austerity itself; it was the inequality of the burden of sacrifice. The lucky amateur, he complained in a passage with a familiar ring, did well from the game: "Manufacturers of well-known goods from fountain pens and energy restoratives to easy chairs and hair-oil shower their samples with lavish generosity in much the same manner as they accommodate film stars. `Stars', too, often sign on the dotted line beneath a newspaper article which bears their name but which sometimes they do not even read, and afterwards they sign the endorsement on the back of the cheque in payment...And so the game goes on, full of make-believe; and yet everybody intimately connected with cricket knows all about it."

The cricket pro of Root's period was meant to be unimaginative and deferential, even obsequious. Root's prognostications about cricket, however, prove to be remarkably far-sighted, and expressed with the nerve of a man who once had the temerity to tell Lord Hawke to stop talking in the slips. Root urged officials to "adapt themselves to the type of cricket which pleases the patrons and is demanded by them", and even traced the outline of a limited-over knockout tournament among the counties: "Make the matches sharp and snappy. So many overs to be bowled by each side if you like, but aim at a definite result in a specified time...The public do not want extensions, they cry out for contractions." Root lived just long enough to see one of his wishes granted: the appointment of a professional captain of England, for which "these democratic times" cried out, because "a title and lots of money doesn't assure the scoring of centuries". Others, like a transfer market, he did not; a few, like penalties for scoring at less than a run a minute, have remained fancies.

Root didn't want to be seen as a `red revolutionary'. Various grandees, like Lady Warwick whose son he coached and Lord Coventry who would take the Worcestershire side to shoot game with him, feature in A Cricket Pro's Lot in admiring cameos. Ultimately, his narrative is a reinforcing one: "This cricket is a great and glorious game. It is played by grand fellows. In spite of my grouses I shall try to play it until the `reaper' bowls me out."

But the Gilbertian air of the title is surely not coincidental: a cricket pro's lot is not a happy one.

Gideon Haigh is a cricket historian and writer