When Amien Variawa took on the might of the Springboks

Remembering the Indian-origin batsman who played a star turn in a rare, forgotten friendly across colour lines in apartheid South Africa in 1961

Luke Alfred

04-Nov-2020

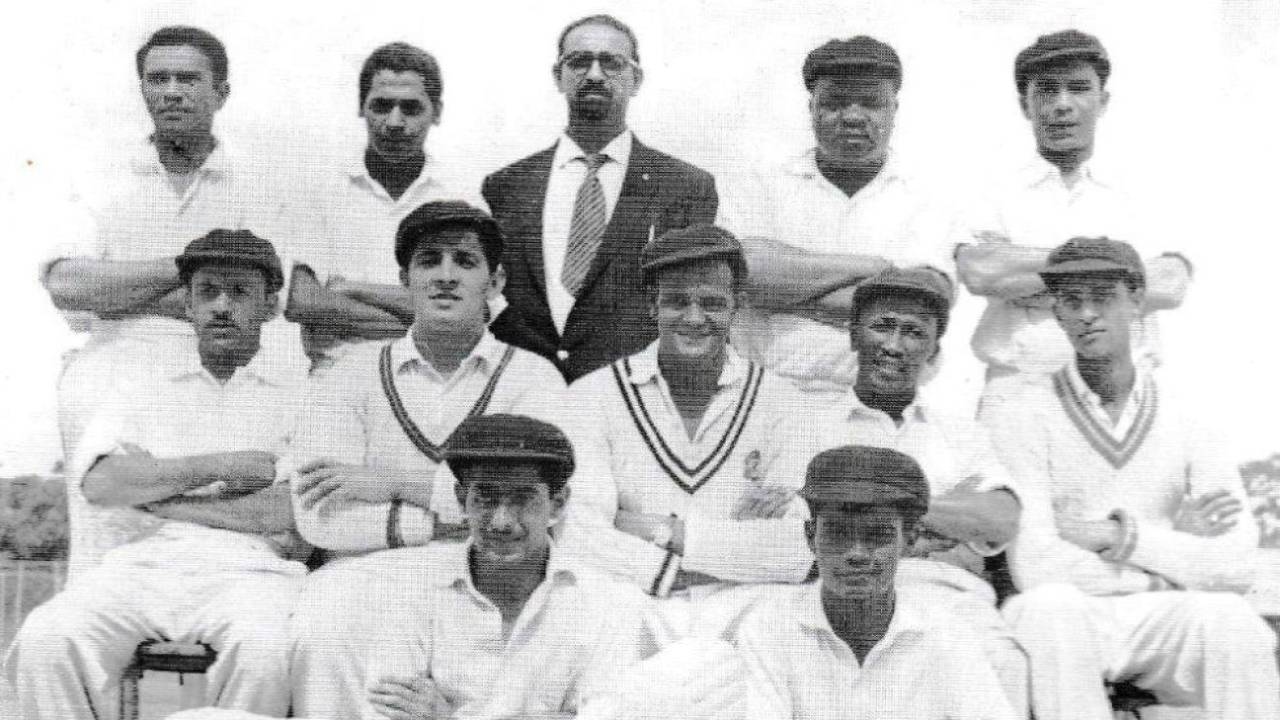

Amien Variawa (standing, first from left) and the SA Haque Invitation side that beat Johnny Waite's XI • Aslam Khota/Across the Great Divide

On the night of March 31, 1961, Amien Variawa took to his bed early. He'd been feeling poorly for days - a touch of the flu - and although there was an important game of cricket to play on the weekend, he doubted he would be fit enough to appear in it.

Just as he was nodding off, a knock at the door. A delegation of team-mates and well-wishers had come round to his home in Vrededorp, Johannesburg to cheer him up. He simply must play, they pleaded, even if he was only half-fit.

This was an important game, a rare friendly across the colour line against an invitation side organised by the Springbok wicketkeeper John Waite. Against them were pitted a team of Indians and black Africans, assembled by the benefactor and businessman Abdul Haque, with Variawa as their star turn. It was now or never, they said. Waite had been quoted in the local papers saying that the "non-whites" needed to show what they were made of. Haque's men, who had been angling for the game for months, needed to step up or shut up.

Variawa was quietly thrilled by the delegation's attention. He made no promises but told them he would do his best. The following morning, at the Natalspruit Grounds, on the edge of Johannesburg's central business district, "Doolie" Rubidge, the Haque's XI skipper, won the toss. Variawa opened the innings with Abdul Bhamjee, who was later to become a charismatic football administrator with a love of satin shirts in infinite shades of purple.

As he walked to the crease Variawa looked around him and saw that Waite hadn't patronised his opposition by picking an under-strength side. Russell Endean, a feature of the Springbok middle order through the 1950s, was part of Waite's team, as was the curmudgeon Sid O'Linn, who had blocked and fretted against England in 1960.

There also were up-and-coming youngsters - one of them, Ali Bacher, was to make a lasting impression as the decade continued - and what looked to be a sharp opening attack made up of Jackie Botten and Ken Walter, both of whom played for South Africa in seasons to come. Haque's men were going to be tested.

Variawa's century in a match in which no one else scored 50 might have signalled a late flowering, but apartheid restricted opportunity and upward mobility, in cricket as in life.

The Haque XI openers managed to see off the Botten and Walter threat, but with Waite's first change came a setback: Mike Macaulay, bowling left-arm over, snuffled Bhamjee (4) and Sayed Kimmie (3) in quick succession. Suddenly it was 26 for 2 and the gainsayers were beginning to mutter "I told you so."

"I was a swing bowler," recalls Macaulay. "Bowling on a hessian mat and a sand outfield didn't keep the shine for very long, but while it was swinging I managed those two early wickets."

Kimmie's dismissal to a Macaulay caught-and-bowled (there were 18 caught-and-bowleds in the match) brought young Ossie Latha, Variawa's brother-in-law, to the wicket. He and Variawa settled in. The scoring rate accelerated when Bacher, fresh out of school, trundled through a spell of innocuous legspin at more than a run a ball.

Slowly the score mounted. The healthy crowd, mainly young Indian men in suits with thin ties and a few autograph hunters in shorts, clutching their books, began to relax. Dared they hope for a big score against the whites?

The match shouldn't have been played, for it was in contravention of apartheid's petty laws, but Waite's influence and a sort of willed ignorance from officialdom kept the security police away. "I remember curry for lunch and a big spread," says Macaulay. "The problem was that I'm allergic to chilli, so I couldn't eat."

Variawa and Latha batted through the afternoon. The hundred was brought up, then the 150. Waite permed his bowlers, giving them second and third spells. Variawa, normally a punishing driver of the ball, had to be careful of the excessive bounce on the hessian mat. He reeled in his shot-making. The total rose.

Latha, who made 45, went with the total on 162 after a 136-run third wicket partnership. Shortly after, Variawa brought up his century, scored in 187 minutes and containing 11 boundaries. He hardly had time to soak up the congratulations before Haque's XI tumbled from 177 for 4 to 207 all out, Botten and Macaulay contributing to five ducks at the bottom of the card. The chilli-averse left-armer finished with figures of 5 for 38 in 16 overs.

****

Born in District Six, Cape Town, in 1928, three years before Basil D'Oliveira, Variawa was one of three brothers, all of them cricketers.

The match scorecard. Variawa was the only player to cross 50•Getty Images

District Six was a lively melting pot of races, a casbah-like area of close-knit dwellings on cobbled streets, full of banana and peanut sellers trundling their wares in handheld carts. Variawa's father was a cotton merchant in a district of merchants and small shopkeepers, his business eventually taking him upcountry to what is called the platteland, or countryside, in Afrikaans. It was here that a young Variawa learned his cricket in the country district leagues.

The family spent time in the rural towns of Lichtenburg and Piet Retief, according to Variawa's son, Nazeem "Jimmy" Variawa, now a school and wedding photographer in his 60s.

As a young man, Variawa found himself in Johannesburg, golden city of opportunity. Here his cricket prospered. The Indian leagues were well-run, with indefatigable characters like Haque organising tours, friendlies and coaching clinics. While facilities were never luxurious - unlike, say, at the famous Wanderers club, where, fresh out of school, Macaulay started out in the tenth team and worked his way up - they were decent. For Indian players and fans alike, the game was an obsession. Such devotion inspired self-reliance. The players knew their cricket history and were nimble of mind.

****

In reply to the Haque XI's 207, Waite's men could only muster 154 (Bacher 37; Rubidge 4 for 41) to which Haque's team responded with a paltry 75. This left Waite's side (effectively the Transvaal provincial side) 129 to win. They scrambled 108 and Haque's team won by 20 runs. They were still basking in glory a couple of days later when the return fixture at the Wanderers was mysteriously cancelled.

Waite had been quoted in the local papers saying that the "non-whites" needed to show what they were made of. Haque's men needed to step up or shut up

The Rand Daily Mail's Dick Whitington detected "shades of Ranjitsinhji" in Variawa. His century in a match in which no one else scored 50 might have signalled a late flowering, but apartheid restricted opportunity and upward mobility, in cricket as in life. By the time of the century against Waite's XI, Variawa had already played for the SA Indians against the Africans in 1955, before being picked as vice-captain for the South African Indians on their tour of Rhodesia and East Africa in 1958. There he joined D'Oliveira in the SA Indian side, captaining the team in D'Oliveira's absence during the third three-day "Test".

D'Oliveira headed off to Middleton in the Central Lancashire League in 1960, qualifying for Worcestershire in 1964, a process smoothed by him telling the county he was three years younger than he was. Latha, now 80, remembers that D'Oliveira and Tom Graveney mooted a possible trial at Worcester for Variawa in the mid-1960s but, for reasons he can't remember, nothing came to pass. He was keen that Latha prosper, though. "Amien did try and help me get across to a club in Sussex - he was willing to put up the money, but my parents weren't keen," Latha says. "By that stage he must have been 35, so his time had passed, but he wanted to see me do well."

Variawa had to be content with inter-provincial tournaments and the Christmas tours Haque organised to the Cape. "[When we toured there at the end of '62] it was the first time I saw the sea," says Hoosain Ayob, a fast bowler and team-mate of Variawa's. "We went to the docks. Up Table Mountain. We went to the 'Coon Carnival' [since renamed the Cape Minstrel Carnival] on New Year's Eve.

Ayob remembers Variawa as a man who liked the horses and a joke, and as a fine driver, offspinner and safe slip fielder in his cricket-playing avatar. "He was a good-looking man, always in a suit and tie. A bit of a charmer, although you would never find him in fights or arguments. His trademark was a white hankie, which he always wore around his neck."

"Would he have played for South Africa under different circumstances?"

"Easy."

An article in a magazine details the rout of John Waite's team at Natalspruit•Getty Images

After his playing days were over, Variawa became a travelling salesman. During the summer, he coached cricket on weekends, driving his son Jimmy's teams all over the Transvaal.

The 1960s were the age of swanky dancehall show bands: El Rica's Dance Band, the Five Pennies, the Santiagos, the Lyceum Combo and the Rhythm Bluebirds among them. According to Ayob, Variawa loved to dance almost as much as he loved to thunder off-drives past extra cover's left hand. In their satin bow ties and pressed suits, the bands played standards across a wide range, including rhumbas, cha-chas and sambas. They also played kwela, the indigenous penny whistle- and saxophone-driven music of the black South African working class.

These nights were looked forward to for weeks. "Fund-raising dances and dinner dances and sporting activities were pretty much what we all did for recreation in places like Vrededorp and Pageview [Johannesburg's equivalent of District Six] in those days," Ayob says. "We'd all take our girlfriends or dates to the Springbok Hall or the Ritz for Friday or Saturday nights."

Dancing out to take on the best bowlers from other lands was an opportunity seldom afforded Variawa, although he continued to move smoothly across the dancehall of life as a salesman. El Rica's rendition of "The Girl from Ipanema" remained one of his favourites. "He was some dancer," says Ayob with a smile.

Variawa's life came to an abrupt and tragic end end on New Year's Eve 1985, when he was involved in a head-on collision while driving with a Turkish friend on a poorly lit road outside of Azaadville, west of Johannesburg. He was 57. His story is cherished by a few but he is largely forgotten, another in the endless legion of South African cricket's unknown soldiers.

Luke Alfred is a journalist based in Johannesburg