A republican prince

Pataudi was a legend when he started. His pedigree, flair, and epic disregard for his handicap, spoke to the anxieties and aspirations of a young India and to its hunger for heroes

Mukul Kesavan

23-Sep-2011

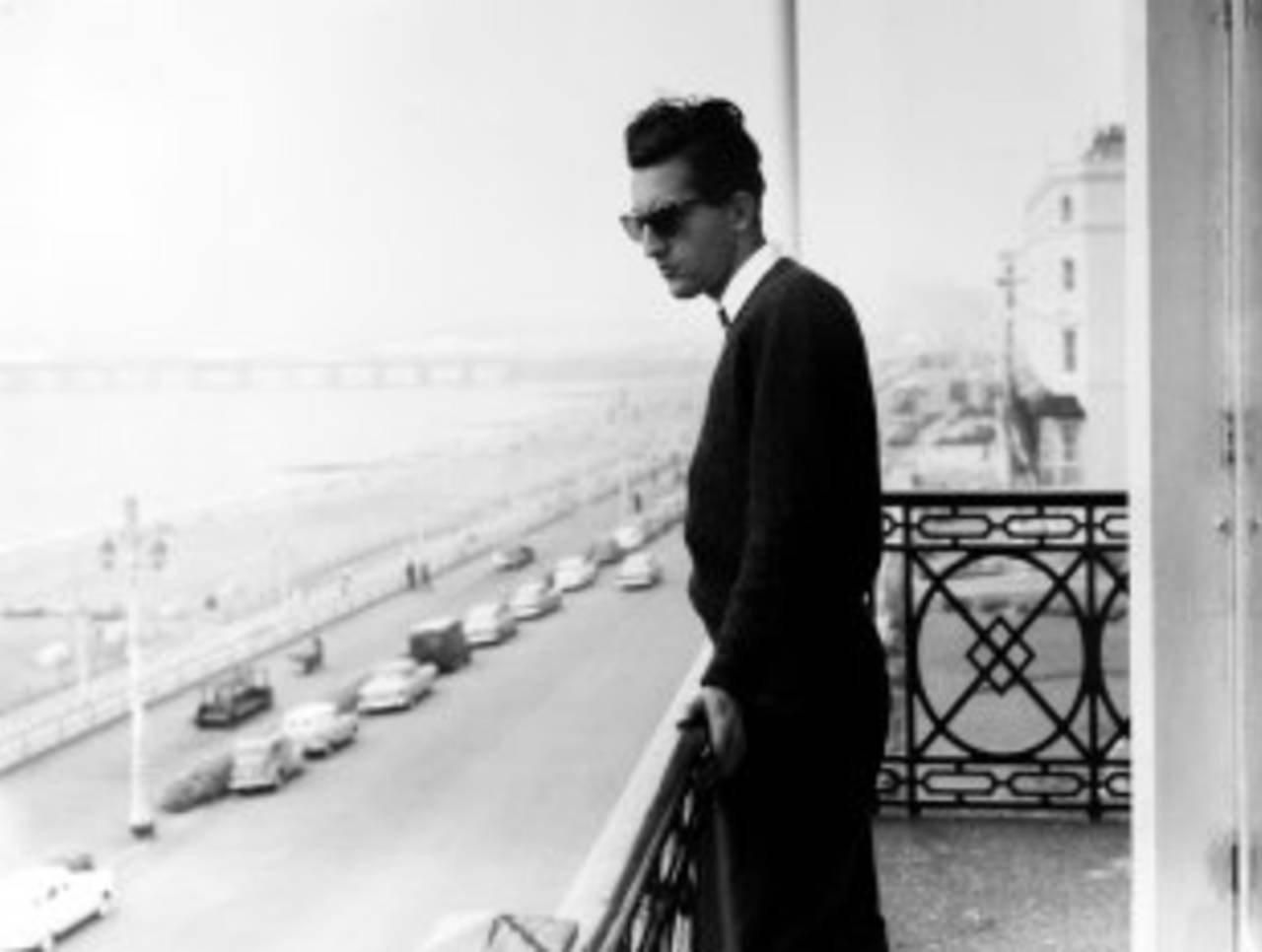

Pataudi: like Shammi Kapoor and the Beatles, his heyday was the sixties • Getty Images

Mansur Ali Khan, the Nawab of Pataudi, was that curious hybrid: a republican prince. Both parts of his personality came together to create the larger-than-life legend that he became, first as an active cricketer and then through the long afterlife that is the lot of every famous sportsman.

His father, the eighth Nawab of Pataudi, was the ruler of a minor principality but a cricketer of considerable distinction. It was a very colonial distinction: educated at Balliol College, Oxford, Pataudi Sr played first for Worcestershire and then for England as the princely subject of a far-flung empire. Before India's independence, in 1946, when his son was five years old, he achieved the double distinction of playing Test cricket for two countries: he captained India against his old team, England.

His son had much to live up to as he came of age in the first decade of the young republic. Born into great privilege (his mother was, in her own right, the Begum of a much grander princely state, Bhopal) he was orphaned early. He was schooled for the most part in England, where he broke all of Douglas Jardine's batting records at Winchester - which gave him particular satisfaction because Jardine and his father had had a famous falling out over the ethics of Bodyline bowling. He gave notice that he wasn't just the son of a famous man but a cricketing prodigy who was likely to eclipse his father.

India in the fifties was a proud young republic, but for its middle classes an education at a famous English public school and thereafter at Oxford still had great cachet. Certainly one reason why Pataudi became India's Test captain after Charlie Griffith broke Nari Contractor's head in the West Indies was because he had captained both Winchester and Oxford. He was absurdly young, just 21, the youngest Test captain in the history of the game. In terms of Test match experience someone like Chandu Borde had the larger claim, but Pataudi's lineage, his English exploits and the fact that he had scored a fifty and a hundred in his first Test series against England persuaded the selectors that he was fit to lead.

It was an extraordinary gamble, the risk mitigated perhaps because the selectors knew they were betting on an extraordinary man. All the runs Pataudi had scored in his young Test career had been made with one functional eye. At the age of 20 he had damaged his right eye in a car accident. He wasn't just a prince; he was already a hero who had overcome a career-ending disability with such savoir faire that the selectors probably felt he could do anything. And they were right.

So from the very start of his Test career, Pataudi was a kind of legend. Schoolboys in the sixties spent inordinate amounts of time trying to work out whether his right eye was real or made of glass. He was the debonair one-eyed prince who had out-Englished the English and who was going to help India master this great colonial game. His pedigree, his poshness, his flair, his epic disregard for his handicap, spoke to the anxieties and aspirations of a young republic, and to its hunger for heroes.

Pataudi played 46 Tests and he captained India in 40 of them. It's hard to believe his career was more or less over before he was 30, so completely did he dominate India's cricketing imagination for a decade. The last series of his eight-year run as captain (before he was replaced by Ajit Wadekar) was the five-Test thriller against Bill Lawry's Australians in 1969, which India lost 3-1. It was the year he married one of Bombay cinema's most celebrated heroines, Sharmila Tagore. Pataudi's considerable charisma was now gilded with stardust.

Like Shammi Kapoor and the Beatles, Pataudi's heyday was the sixties. Between 1962 and 1970, he captained India in 36 Tests, of which India won seven - not, on the face of it, a remarkable record as captain. What the figures conceal is the panache and flair with which he led sides that ranged from middling to poor. He led India to their first series win abroad, against New Zealand, a notable achievement for a side that had always travelled badly.

Faced by a famine of fast bowlers, Pataudi rejected the orthodoxy of a "balanced" bowling attack and bet the house on attacking spinners. His greatest legacy was the golden age of Indian spin bowling, featuring that remarkable quartet, Bedi, Chandrasekhar, Prasanna and Venkataraghavan. To back them up he helped create the best cordon of close-in fielders Indian cricket had ever seen: Eknath Solkar, Wadekar, Venkatraghavan and Abid Ali. He led by example; he was India's best cover fielder right through his career.

As a batsman he hit half a dozen centuries and 16 fifties for a respectable average, 34.91. Did he count as a batsman? Yes he did. There were the two fifties he made against Bob Simpson's Australians that helped India win the Bombay Test in 1964. There was the fifty and the hundred in a losing cause at Headingley in 1967. India lost every Test in that series, but listening to Test Match Special on the BBC's World Service, Indians were content that their hero had top scored in India's first innings and then hit a wonderful 148 out of a total of 510 to avoid a follow-on. (India lost respectably, by six wickets).

Schoolboys in the sixties spent inordinate amounts of time trying to work out whether his right eye was real or made of glass. He was the debonair one-eyed prince who had out-Englished the English and who was going to help India master this great colonial game

Listening to John Arlott and Brian Johnston speculate about the batting heights Pataudi might have scaled with two good eyes, his countrymen forgave him all the innings when he had scored nothing and hadn't seemed to care. Best of all, there were the two fifties he hit against the Australians in the Melbourne Test of 1967-68, where, literally hamstrung, he hit 75 and 85, "with one good eye and on one good leg… " (Mihir Bose, A History of Indian Cricket). India still lost by an innings, but Indians were used to finding individual consolation in collective failure and the thought of Pataudi, hobbled but heroic, hooking and pulling his way to gallant defeat, was consolation enough.

He wasn't part of the history-making team that won away series against West Indies and England in 1971, having been dropped as captain and replaced by Wadekar. To add insult to injury, by the end of that landmark year he wasn't a Nawab either: Indira Gandhi abolished princely titles and the privy purses that went with them.

With hindsight, he should have retired then but didn't. He returned to Test cricket to play part of a series under Wadekar's captaincy against a touring English side, and then made an unexpected comeback as captain, when Wadekar retired after a disastrous tour of England in 1974, having lost everything. Pataudi led India in four of the five Tests during West Indies' 1974 tour, and though the rubber was a thriller (West Indies won 3-2), he personally had a terrible run with the bat. The swansong was a mistake; he was too slow for the game at the highest level and it showed.

But given his achievement, this was a minor misjudgment. When Pataudi took charge of the Indian team, it was a team that didn't believe they could win or bowl the opposition out twice. He left them ready to hold their own against any opposition, with the self-belief necessary for success.

In retirement he dabbled unsuccessfully in electoral politics, edited a sports magazine, and briefly became an expert commentator. He had a brilliant television manner: sharp, sardonic, and occasionally rude. When Asif Iqbal led the Pakistan team to India, Pataudi chatted to him on camera. He asked Iqbal, deadpan, if he planned to change countries again. Asif Iqbal had migrated to Pakistan as a 17-year-old after playing cricket for Hyderabad, Pataudi's first-class team, and the great man hadn't forgotten. The audience drew in a sharp breath, Asif, to his great credit, smiled, and the moment passed. It was a quintessentially Pataudi moment.

Luckily he didn't make it a living and his fans didn't have to watch him age into a television hack. A natural reserve also had him keep his distance from India's cricket establishment, except for a brief, ill-fated stint with the IPL. He remained untouched by the squabbles and sleaze that attended cricket's transformation into big business in India. As a consequence, death finds him happily embalmed in fond radio memories: still tigerish in the covers, still a prince amongst men.

Mukul Kesavan is a novelist, essayist and historian based in New Delhi