The importance of Afghanistan's exuberance

Afghanistan have already breathed life into this tournament. We've seen enough to know that the ICC should reconsider contracting the ODI World Cup.

Against South Africa, Afghanistan briefly raised the possibility of the Proteas scoring 438 runs across two T20 matches and losing both. Watching Afghanistan's defeat to Sri Lanka was equally captivating. As the world champions struggled to finish off the upstart challengers, Afghanistan were simultaneously fighting hard and falling apart. Their spirit and self-belief were terrific, their ground fielding was abysmal. The captain gestured with his arms; bowlers glowered; between skilful leggies and googlies, Rashid Khan, 17 years old, pushed his side parting across his forehead (had his mother had given it one last comb as he left the door?); outfielders shook their heads; long barriers disintegrated. It was, in its rawness, utterly majestic. So long as you weren't the coach.

The match, as an uncensored carnival of emotions, resembled the village green rather than the professional sports pitch. "Village" may sound like an insult, but not from every perspective. "If someone called me a 'village cricketer' it was supposed to be a hurtful slur," Andrew Flintoff once told me. "And I'd think, 'Cheers mate. If it looks like I'm enjoying this, something must be going right."

In the memorable phrase of ESPNcricinfo's Sharda Ugra, Afghanistan "bring to a somewhat tired global community the fresh, bracing air of the mountains". Their performance against Sri Lanka was sport without the poker face that we all learn, to a greater or lesser degree, to put on. Afghanistan's players weren't just failing to hide their emotions, they weren't even trying. "But they lost, so what does it matter?" says the cold rationalist. We'll come to that too.

As I watched the match, there were two voices in my head. The first said: "A bit of polish, more street smarts, a cooler temperament, a dispassionate mind - then this team will be hard to beat." The second voice: "No hurry, though! I'm enjoying this, just as you are. Don't grow up too fast." May you stay, implored Bob Dylan, forever young.

Songs of Innocence and Experience gave William Blake not only the title for a collection of poems in the late 18th century but also a way of seeing the world: from innocence to experience, the progress of a life. It is also the journey of a player.

Two questions follow. Can a player - or a team - benefit from experience while retaining some of that magical innocence? If not, how can the game as a whole preserve that exuberance and authenticity, one fresh voice among a more jaded chorus?

Let's be honest, the cycle of hope and disappointment, performance and criticism, does take a toll. Praise is as dangerous as criticism. Players who once performed naturally and instinctively, when it is "explained" to them, can find the whole thing dangerously demystified. "All reviews are bad for you," argued the poet Ted Hughes, "especially the good ones."

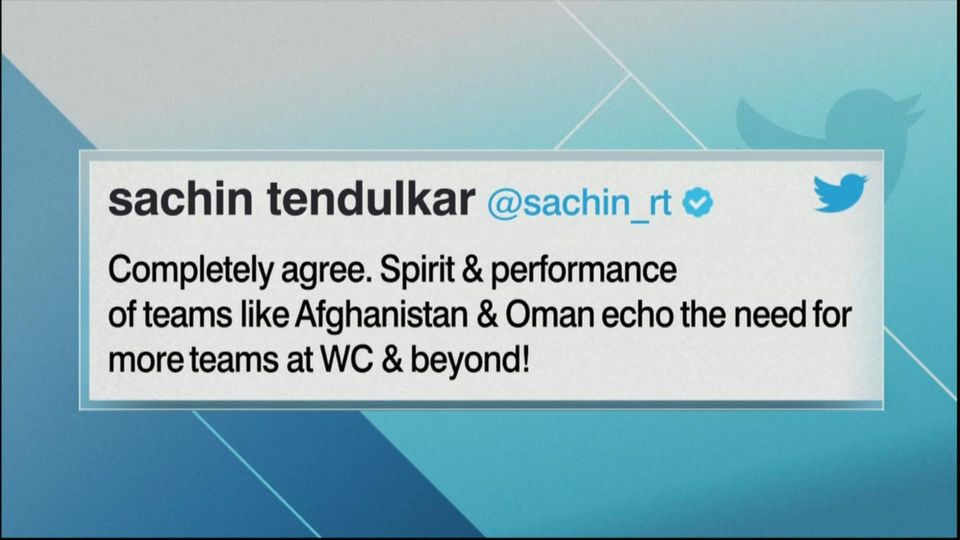

If Afghanistan played as many matches as the leading international teams, they would, most probably, undergo the same series of trade-offs - the benefits of savviness earned at the expense of exuberance. That raises the wider point. The club of nations at cricket's top table - in this tournament, ten countries - needs a constant supply of new voices to refresh and renew the competitive conversation. As one team graduates and evolves into maturity, the game needs the next raucous newcomer, the new rough diamond, to be polished on the international stage.

I admit that it is not easy for tournament organisers to get the perfect balance between brevity and breadth. But the game urgently needs to develop the conveyor belt of international teams, which has slowed alarmingly. Afghanistan have the potential to develop into a seriously competitive ODI/T20 international team very quickly. That would be a major victory, which, in turn, would bring a further necessity: to find the next Afghanistan, to encourage and develop the latest international voice. International cricket cannot become the same old teams stuck in the same old rivalries.

What about innocence and experience within individual players and the old world order? Near the end of my career, I was practising in the nets at Lord's when the Afghan team rocked up for a net. They were trying to add cricketing experiences, seeking new sophistication while playing in new conditions in England. I was in the adjacent net, my head down, in every sense, absorbed with my own technique - the next ball, the next game.

How familiar and routine my practice was, how lacking in sparkle and joy. The Afghan net session was the opposite, bubbling over with enthusiasm, unbounded by having done it all before. I wish now I had taken off my pads and talked to them instead of grinding away in a familiar groove.

I think the best sportsmen do retain psychological freshness, but, odd as it sounds, their innocence has to be worked at. They polish techniques and tactics while retaining an emotional openness. Aged 30, already a serial winner, Roger Federer put it like this: "The problem with experience is that you become too content with playing it safe. I have to push myself to stay dangerous, like a junior - to play free tennis."

Brendon McCullum talked about channelling the mindset of the amateur who can't wait to strap on his pads for his one knock a week on Saturday. The greater the experience, the greater the need to work at retaining innocence. Sport is at its most rewarding, for players and spectators, when we do not take refuge behind self-protective masks. The bravery of not pretending, transmitted to opponents and fans alike, elevates the game. That was also Tom Stoppard's definition of love in his play The Real Thing. "Knowing and being known... the real him, the real her, in extremis, the mask slipped from the face."

So good luck to Afghanistan, as they learn from the rest at the World Cup. But I hope the exchange of ideas is mutual. Experience can learn from innocence, not just innocence from experience.

Ed Smith's latest book is Luck - A Fresh Look at Fortune. @edsmithwriter