Ashes moments: Cook soars, Australia slide

ESPNcricinfo looks back at a few of the memorable moments from England's triumphant Ashes campaign, from a frenzied start at the Gabba to the decisive blow on Boxing Day at the MCG

Andrew McGlashan

08-Jan-2011

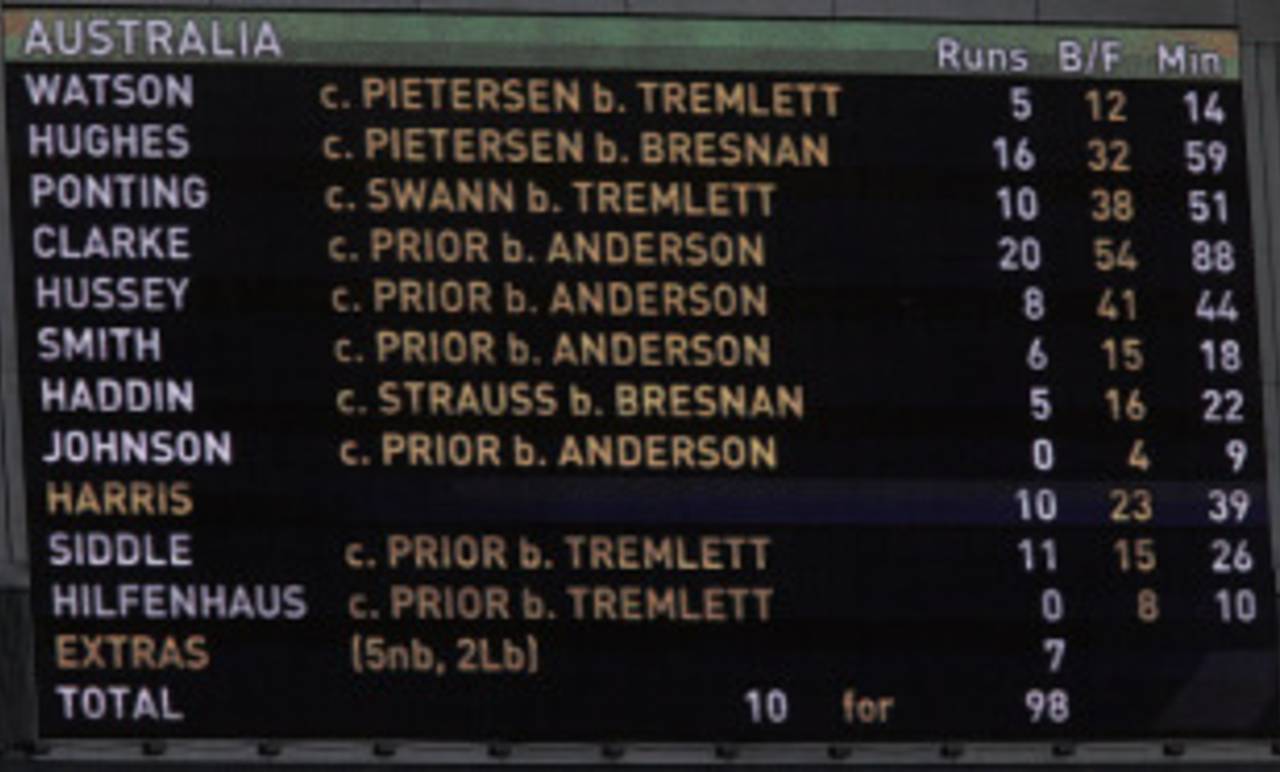

When Australia were routed for 98 on the first day at Melbourne, it was clear the Ashes weren't going anywhere • Getty Images

Cook lays his marker

The tension on the first morning of the series was immense and amid the frenzied atmosphere Andrew Strauss cut the third ball straight to gully. England needed calming down before bad memories came flooding back. Alastair Cook was called a 'weak link' before the series, unsurprisingly given his poor numbers against Australia, but he soon began setting the record straight. No one knew what riches would come his way during the series, and 67 pales in comparison to 235, 189 and 148, but in many ways it was the most important innings. It gave England time to breath and proved there was nothing to fear in the Australian attack. He left well, refusing to be drawn into the drives that previously brought his downfall, and the impact was that England reached the relative comfort of 4 for 197. Then came Peter Siddle, who began his hat-trick by having Cook caught at first slip and a few moments later the innings was spiralling again. Cries of 'same old England' could be heard from the fearsome Gabba fortress but this was nothing of the sort. This was a new England team, ready to prove doubters wrong. And none more so than Cook.

Captain's innings

Still, England were well behind after three days in Brisbane. Mike Hussey and Brad Haddin had added 307 to build a lead of 221 and it all looked set for a home win. Andrew Strauss, though, was determined that he wouldn't be remembered for that first-day duck. For a moment it appeared he may have bagged a sickening pair when he padded up to Ben Hilfenhaus's first ball; it was given not out, Australia reviewed and it was just going over the stumps. Strauss and Cook survived a torrid hour on the third evening and emerged primed for a famous rearguard the next day. Strauss stood up to play his most important innings for England. It was a statement of the highest order as he took the attack back to Australia with cuts, pulls and, in the clearest sign of his form, straight drives. He even used his feet to loft the spinners straight and suddenly England were past 100, then 150 and the deficit was nearly erased. Strauss's hundred came up with a late cut off Xavier Doherty and although he was stumped off Marcus North England didn't lose another wicket as they rewrote the record books with 1 for 517.

3 for 2 or 2 for 3?

So who had the momentum after Brisbane? It took less than an over to find out despite Adelaide being predicted as a nailed-on draw. Rarely has a Test begun in such extraordinary circumstances. After three dot balls, James Anderson speared a delivery at Shane Watson's pads which rolled into the leg side. He set off for a single, but Simon Katich didn't move straight away. Jonathan Trott, one of England's least mobile fielders, collected the ball and with one stump to aim at hit direct. Katich had a diamond duck, yet the drama wasn't finished. Ricky Ponting prepared for his ball against Anderson; it was a perfect outswinger on off stump which drew Ponting forward and took the edge to second slip. Five balls, two wickets, no runs. And still more. In Anderson's next over another fine outswinger lured Michael Clarke into a flat-footed drive and Graeme Swann took his second catch. The pitch was flat - as England later proved by making 5 for 620 - and the hosts were in tatters. Ponting's world was starting to crumble.

Good call

It wouldn't have been an Ashes series without at least one insane fluctuation in fortune and it duly arrived at Perth as England were hammered by 267 runs to breathe life back into Australia. They were bullish heading to Melbourne - that word 'momentum' was as popular as turkey and stuffing on Christmas Day - but Boxing Day dawned cloudy, cool and damp. It was a home-from-home for England and Andrew Strauss won the toss. Four hours later - and it was only that long because of a rain break - Australia were humbled for 98. James Anderson made the ball talk, Chris Tremlett provided brutal lift and Tim Bresnan slotted perfectly into the holding role that Steven Finn struggled to perform. By the end of the first day England were 0 for 157. The Ashes weren't going anywhere.

Bresnan swings it

England finished the series with only half of their attack from the first Test. Yet it was part of the planning. Tim Bresnan had impressed against Australia A in Hobart but was always going to take a back seat early on in the series. England came with a plan to target Australia from a height with Stuart Broad, Steven Finn and Chris Tremlett. But they were also ready to adapt. Broad was already home injured and Finn had proved problematically expensive despite taking 14 wickets so it was Bresnan's turn. He'd played just two first-class matches since September but settled straight into his task, claiming Phil Hughes and Brad Haddin. However, he really came into his own in the second innings when he reverse swung the ball with devastating effect on a surface that had lost its first-day greenness. On the fourth morning he claimed Ben Hilfenhaus to retain the Ashes but, as with the whole team, wasn't finished yet. In Sydney his old-ball skills came to the fore again with five wickets in the match and England's pace-bowling stocks were looking very deep.

Beer's no-ball

In the end Australia were hammered, yet for a time on the second day in Sydney they were clinging to the prospect of a scarcely deserved series draw. Mitchell Johnson had flayed 53 to lift them to 280 and when he bowled Jonathan Trott for a duck, to leave England 2 for 99, memories of Perth were emerging all round. Cook was standing firm, laying the foundation yet again on 46, when he faced the debutant Michael Beer. He came down the track but wasn't to the pitch and lofted a catch to mid-on. Beer celebrated his maiden Test wicket and Cook was walking off. Then Billy Bowden signalled he wanted to check the frontline. Surely a spinner hadn't overstepped? But there it was. Beer's heel was fractionally over the white line. Emotions swirled around Beer's mind and Cook wouldn't depart for another 143 runs. The rest, as they say, is history.

Andrew McGlashan is an assistant editor at Cricinfo