Match-fixing

At the turn of the century, cricket felt a tremor stronger than any it had known till then

Amit Varma

Jun 11, 2011, 3:01 AM

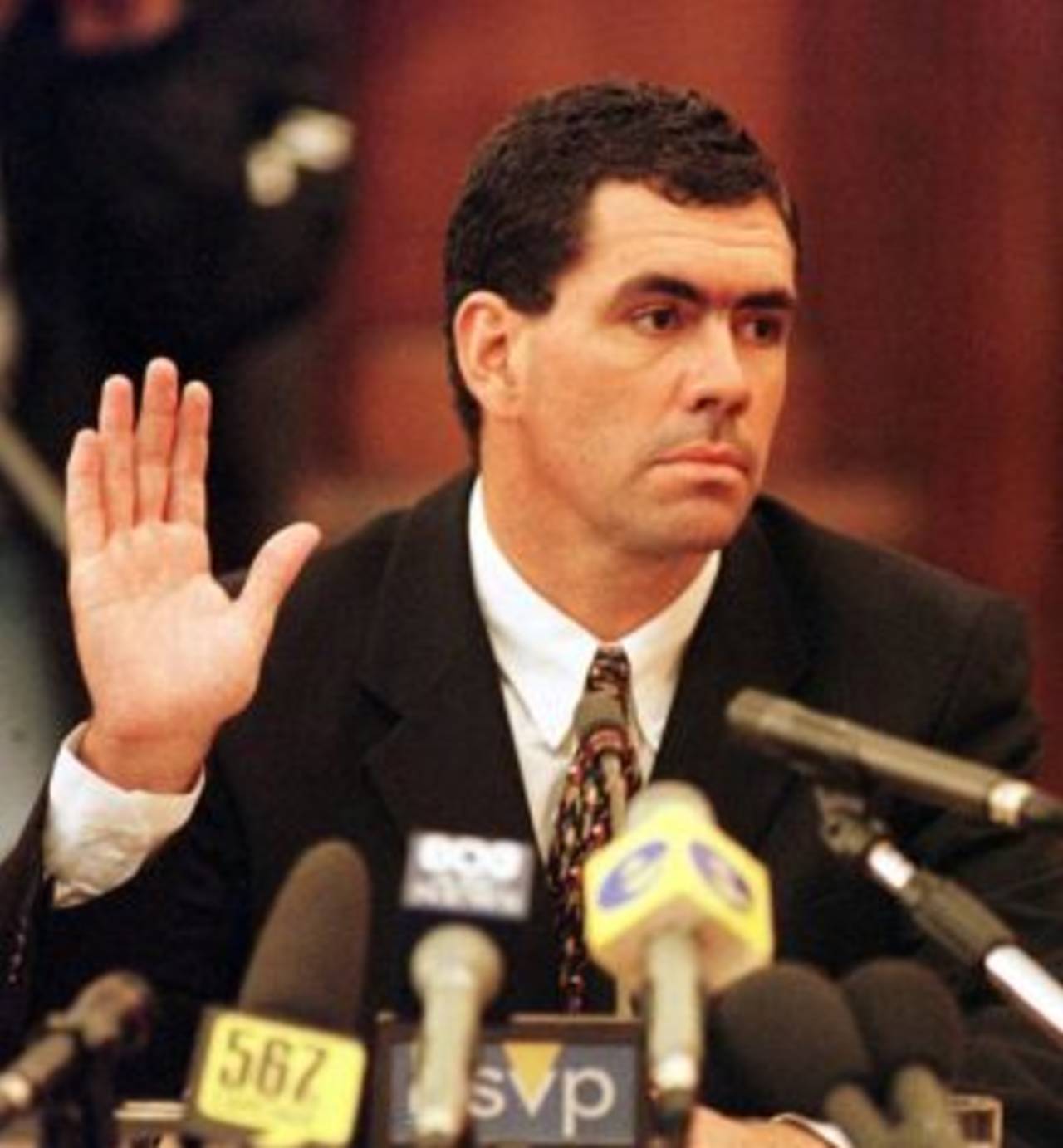

Cronje's admission of guilt brought the cricket world out of its denial about the game being all clean and fair • AFP

2000

How would we ever watch cricket again? On April 11, 2000, when Hansie Cronje confessed to taking bribes from bookmakers, cricket lost its moral centre. Of all sports, this one was associated with a certain old-world set of values - thus the phrase, "it's just not cricket": fairplay was part of the fabric of the sport. But after Cronje confessed, the threads unravelled and it became apparent that match-fixing wasn't restricted to a few arbitrary occurrences, that he had indulged in it time and again, that he had tempted others, and that he was just a small cog in a large, oily wheel. Cricket had entered the modern age and had been consumed by its worst excesses.

It should not have come as a surprise. Stray allegations of match-fixing had been made for years, but the game was in denial. It could stand the smoke but not deal with the thought of the fire that was inevitably causing it. At worst, match-fixing was looked at as a subcontinental malaise, which the wider world of cricket was immune to. Then the storm broke.

Cronje, a born-again Christian, one of the most respected captains in world cricket, and an icon of post-apartheid South Africa, was an unlikely person to have sold his soul.

And as the commissions of inquiry in various countries went through the motions, skeletons tumbled the world over. Mohammad Azharuddin and Saleem Malik were banned for life, and various other players, from all the Test-playing nations, were implicated.

Was match-fixing a disease or a symptom? Betting has existed in cricket for decades, but in terms of commercial turnover it burgeoned only about a decade or so ago. The growth of satellite television in the subcontinent in the 90s delivered to cricket an audience - and a commercial potential - many times what had previously existed. Feeding this was one-day cricket; the number of ODIs burgeoned, especially for the subcontinental teams. Many of these were often inconsequential to a series or a tournament. And betting was rife. Illegal in India, it was controlled by the underworld, and the turnover on a single one-day match involving India could, according to the CBI report on match-fixing, reach the "hundreds of crores". It dwarfed the revenues the game, let alone the players, made legally. Something had to give.

It was thought that the life bans to Cronje, Azharuddin and Malik would act as deterrents to other players who were tempted to underperform for money. And to a large extent they did. There was greater policing - the ICC's Anti-Corruption and Security Unit was set up in 2000, following the "corruption crisis" - and many players informed the ICC of suspicious approaches made to them. But every time there was an upset, it would be looked upon with suspicion. And to a certain extent the paranoia was justified.

The Delhi police had revealed the first scandal through phone-tapping. Ten years later a British tabloid broke another one via hidden camera. A News of the World journalist went undercover and taped a man claiming to be a player agent saying he could get certain Pakistan players to bowl no-balls at specific moments during the Lord's Test. The tape was released a day after the no-balls were bowled at the times he specified, and the ICC launched an investigation into the affair. Mohammad Amir and Mohammad Asif, the bowlers in question, and their captain, Salman Butt, were found guilty of spot-fixing and handed bans.

Amit Varma is a former managing editor of Cricinfo. This article was first published in Wisden Asia Cricket magazine in 2003