The embodiment of a Yorkshireman

Brian Close was courageous, of course, but also outspoken, indestructible, and bloody-minded

David Hopps

Sep 14, 2015, 3:53 PM

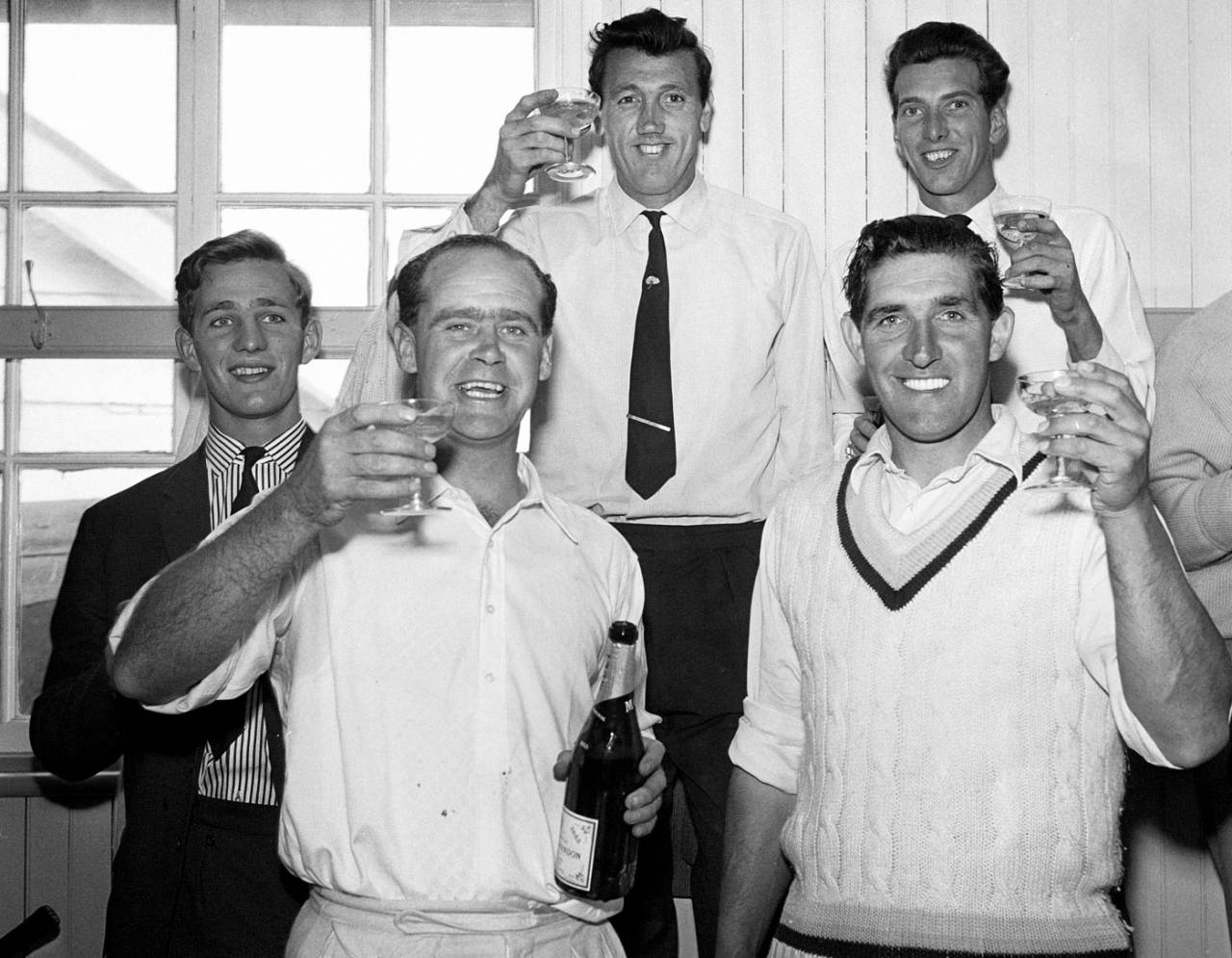

Brian Close (front left) with Yorkshire team-mates after winning the County Championship in 1962 • PA Photos

Yorkshire's cricketing greats are routinely referred to by a single name. But it can run much deeper than that. Over the years, each name has often become shorthand for a dominant emotion. So Fred equals pride. Boycs: opinion. Illy: knowledge. Dickie, an umpiring great allowed to play a guest role: comedy.

The greatest unspoken accolade, though, rests with Closey. To equate Closey with courage would be accurate enough, because surely there has been no braver cricketer to take to the field, but there is something greater at work. Alastair Campbell, the former Labour spin doctor, got it right in his tribute: "Yorkshire in human form."

Not just immensely brave but forthright, genuine to a fault (not that fault would ever be admitted) and revered even more because of a foible or two, Closey came nearest to representing the traditional essence of Yorkshire manliness.

It is often suggested that in Yorkshire fallibilities are not forgiven easily, but they were forgiven more than most with Closey. The enormity of his assertive yet affable personality insisted that must be so. He took admirable human characteristics to the point of absurdity, so much so that laughter and rueful head-shaking were never far away.

It was the mid-1980s, when I joined the Yorkshire Post, a callow observer of the cricketing scene, before I came across him regularly. If Closey was in the bar, there would be trenchant opinions worth hearing. He would draw on his cigarette, lay it precariously on the bar and then pour forth. You had not lived until you had been benignly jabbed in the chest by DB Close's index finger as he emphasised a point.

When he lost his thread - names were not a specialty - he would add a few "bloodys" and intensify the jabbing. The fact he was so opinionated was part of the fun and could send you chuckling into the night. They were bruises to wear with a similar pride to how he wore his from Michael Holding at Old Trafford in 1976. How we feared for him that day as we cringed at his demented, bloody-minded heroism.

Not just immensely brave but forthright, genuine to a fault and revered, Closey came nearest to representing the traditional essence of Yorkshire manliness

Apparently, he could be a reckless driver, too. To ring his car phone in search of a Yorkshire team was to take part in a white-knuckle ride as he forgot names, suggested you filled in the rest, threw in a random opinion or two, and complained about the driver who had just cut him up at 100mph when you knew that DB Close would be doing 110, probably circling some dodgy racing tips in the Sporting Life as he did so.

To Closey's mind, opponents did not just have weaknesses that might be exploited, they had no answer to his insights. Don Mosey told in We Don't Play It For Fun, his affectionate history of Yorkshire cricket, that Close once got Ted Dexter out with a full toss and would have sworn blind that he had exploited a weakness even if the next 1000 full tosses had flown to the boundary. His intuition was often more reliable than that.

He never fulfilled his teenage promise - even his own autobiography, memorably called I Don't Bruise Easily, called him "the most spectacular failure of the age" - although to listen to him you would have imagined that all records would have fallen his way but for the misalignment of the planets. Over-ambitious dismissals were plentiful. But his significance went way beyond his statistical performances, or so we told ourselves, overshadowed by his glorious, all-consuming desire to compete and win. His team ethic was so strong it spoke not of teamwork but of community. He bollocked and moved on, his criticism washed down by generosity.

Along with the courage came the lapses of concentration. Along with the overpowering search for victory came an impatience to make things happen. Along with the insights came the daftness. But you could not successfully captain that Yorkshire team of strong personalities to four Championships without engendering great respect. As for England, he led them seven times, won six and drew one.

First glimpse of a hero: Close fields at short leg to the Nawab of Pataudi at Headingley, 1967•PA Photos

Close loved the duel not the discipline, and if his mind wandered, the analytical approach and concentration was often left to Raymond Illingworth, his vice-captain. The cry of Jimmy Binks, Yorkshire's wicketkeeper that "t'rudders's gone" became an alert that a game had gone awry and, as long as I played club cricket, years after his retirement, it was still occasionally heard on grounds around the county, as if in tribute.

"As you get older it is harder to have heroes, but it is sort of necessary." The words of Ernest Hemingway. And so it is for me with Close. The heroes of childhood have begun to return in later life, just as important now as they were then. Then they were infallible. Now the fallibilities no longer matter. He believed in Yorkshire cricket with unimaginable passion and his pursuit of that belief to the nth degree was what mattered.

One of my first memories of Test cricket is of Close stood at short leg to the Nawab of Pataudi at Headingley on India's 1967 tour. The Indian's name intrigued me, but it was Close, legs braced, hands outstretched, and breeze-block forehead jutting towards the batsman, which held my attention. He was oblivious to danger.

He believed in Yorkshire cricket with unimaginable passion and his pursuit of that belief to the nth degree was what mattered

You know the cricket season has begun, the comedian Eric Morecambe observed, when you hear the sound of leather on Brian Close.

He told of something indestructible; there was something in his immense, unyielding, occasionally hare-brained stubbornness that I was coming to understand was the essence of where I was born.

Around that time, I was playing on a disused railway embankment, a victim of the Beeching cuts, and for reasons long forgotten, perhaps never understood, someone threw a stone and struck me on the forehead. The blood was stemmed and I sported a big plaster. "You look like Closey," Dad said. It was as near as I ever got. What most of us would give for just half of his courage.

Close, to my young mind, became a Yorkshire dissident, wronged by the powers-that-be down in the South, who often seemed to prefer some soft-fleshed, privileged chap, name of Cowdrey rather than our rough-hewn hero with the rebellious, self-reliant expression, the unrelenting defensive block and the ungainly lofted blows. I was proud that, like Close, I played golf right and left-handed, the only difference being about 40 shots a round. He was our rebel and we had utter certainty - as did he - that he was right.

That he was stubborn came with the territory. As Bernard Ingham, in Yorkshire Greats, wrote: "Yorkshire greats are invariably born with the awkward gene that is characteristic of the Yorkshire species. Their DNA is richly endowed with gritty determination, a wilful refusal to give up and a sheer-bloody-mindedness that eventually prevails."

Conflict was inevitable, not just with those down at Lord's but with the county he fought tooth and nail for. In the 1970s, deeply wronged by a Yorkshire committee that had a dangerous belief in its own hegemony, he was invited to resign and upped sticks to Somerset. We used to holiday there and Dad had once suggested on a long overnight drive in an old Ford Popular that England would be a better place if the Yorkshire border connected directly with Somerset, so it seemed a good choice.

He worked wonders, and was a vital influence on the fast-emerging Ian Botham. The only time Somerset saw him in pain, the old story goes, was when, given to wandering around the dressing room naked as he made a trenchant point or two, he came into unfortunate contact with a freshly boiled kettle.

Present him with any sporting contest and he would want to win. He was an unlikely captain therefore in a jolly between the Yorkshire committee and the Yorkshire media in the late-1980s, a match designed to build relations between the two. Close, just back from a club trip to Ireland, made a quick half-century, and later in the day, with the press requiring 37 off the final over, and after checking the match was won, he agreed to allow the county's president Viscount Mountgarret to have a perambulation.

The first ball, a triple-bouncer, was called wide, as was the next. The first legitimate delivery sailed over midwicket for six. The game looked on. Closey's competitive hackles rose. Striding stiff-legged towards Mountgarret, who was trembling with unease at what was to follow, he unleashed: "Bloody pull yourself together… my Lord." He was first at the bar later, talking of a victory that had never been in doubt.

David Hopps is a General Editor at ESPNcricinfo @davidkhopps