1993 vintage

Twenty years ago things were different in the country that had only started out on the road towards becoming cricket's economic powerhouse

Sidharth Monga

02-Aug-2013

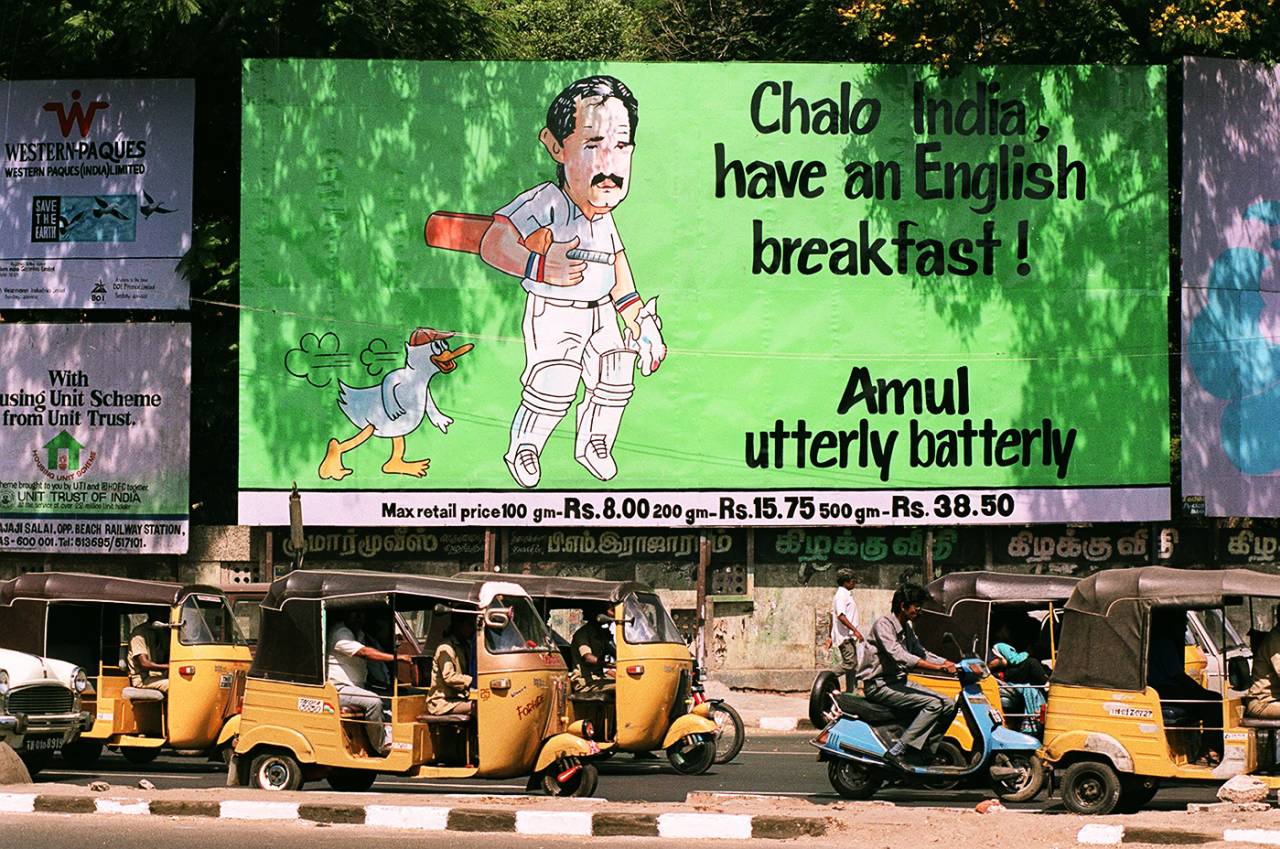

An advertising hoarding references England's tour of India in 1993 • PA Photos

In the winter of 1992, in small-town India, up in the north where watchmen were the only people outdoors, Mr Dayal would be woken up at 6am. He had to be woken up tactfully. The kids would never go to his house alone; there is strength in numbers. Still, it had to be different kids everyday. You couldn't sound too demanding outside Dayal's house, but you had to be firm. India were in Australia to play Tests, a tri-series and the World Cup; you needed him for months.

Doordarshan, the government TV channel and the only channel, would go off every night at 10pm, leaving just snow on the TV. It would come back at some time when you were in school. (Wonder what insomniacs did back in the day.) Technically, the channel relayed still, but we would lose pictures in small-town northern India after 10. Dayal was the man whose job it was to block the signal every night at the Doordarshan relay station and restart it in the morning. We believed there was a switch in the station he had to flick on. He was a powerful man. He shouldn't really have told his neighbours of his occupation. From his disposition every morning, you could tell he wasn't a cricket fan either.

Back then cigarette brands such as Wills and Benson & Hedges were still allowed to sponsor tournaments, sweetened aerated drinks were not even close to taking over the cricket market, and kids in India chewed Big Fun bubblegum. It didn't promise you bright teeth or fresh breath. You had toothpaste for that. In fact, Big Fun didn't even run advertisements, but any kid would gladly spend on Big Fun, even if it was the last half rupee he ever got.

Everyone knew the secret was inside the wrapper. You had to be careful unwrapping it, lest you tore the cricket card inside. Every piece of gum - syrupy and hard - would be worth either a certain number of runs or a wicket. Viv Richards always brought six runs. Kapil Dev was the best: six or out. Ravi Shastri could either be a single or a wicket. Mohammad Azharuddin was always a four; you could imagine he had taken it from outside off and hit it through midwicket. You collected runs and wickets and got goodies: posters, books etc. If you collected 250 runs and ten wickets, it brought you a grand prize of some sort.

Clearly, even after making all allowances for inflation, there was less money and more time to spend back then. Now you go to a Nike store and buy a replica team jersey. Back then, Nike, in many cricketing countries, was nothing more than a tick on the headband around what we thought was Andre Agassi's real hair. You would often get to watch only parts of Agassi's matches because Doordarshan had to cut away to news. Just to tease you, it would bring you the live feed briefly during the newscast and cut away again, 30 seconds later, at second serve on a break point. If Doordarshan had telecast the Hamburg WTA event of 1993, you can rest assured they would have broken for the news minutes before Monica Seles got stabbed.

Now you go to a Nike store and buy a replica team jersey. Back then, Nike, in many cricketing countries, was nothing more than a tick on the headband around what we thought was Andre Agassi's real hair

Apart from time, you had to spend imagination back then. And you had to believe what you were told. You had to believe Nostradamus had said the world would end in 1999, and you had to believe he would be correct. You had to believe India could never beat Pakistan on a Friday. You had to believe Kris Srikkanth was drugged by Pakistan players the night before he scored 5 off 39 in the World Cup match in 1992.

Back then, no one called losing games choking. Because those were not chokes. Today every panic-ridden collapse or poor performance on the big stage is called a choke. And there used to be a lot of panic with Wasim and Waqar around. A true choke was what Jana Novotna had in the Wimbledon final of 1993. She was 6-7, 6-1, 4-1, 40-15 against Steffi Graff, but became too cautious and completely forgot what came to her naturally. And lost. Of course we were watching the news when it happened.

Those were the days before Sachin Tendulkar began opening. Shane Warne bowled that ball of the century in 1993. It was not quite the age of radio, but it was also just before the capitalist explosion in India. Options were coming in. Even people who didn't have relatives abroad could now buy a Sony VCR. They could use it to play smuggled prints of Pakistani comedy skits, which, like anything forbidden, became more popular than what was available locally. The government had only just opened doors to foreign investment; it was called economic liberalisation. The ICC hadn't yet employed sleuths to measure the size of logos on batsmen's thigh pads to protect the interests of the "official" cola.

Yet it is possibly only nostalgia that makes us feel it was a more innocent age. India was going through hell. Punjab hadn't yet fully recovered from terrorism when Bombay was set ablaze in response to the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya. Harshad Mehta, the scam artist who exploited various loopholes in the Indian stock market, alleged that he had bribed the prime minister Rs 1 crore, all cash, in a suitcase dragged to the PM's 7 Race Course Road residence.

Even back then, even without Twitter, Facebook and suchlike, we in India had begun to acquire the ability to be easily scandalised and offended. The song, "Choli Ke Peeche Kya Hai [What's behind the blouse?]" from the film Khalnayak, which released in 1993, created a huge controversy, never mind that Bollywood had always relied on risqué humour. Journalists like Times Now's Arnab Goswami - who today lead voices of outrage, sometimes fairly, sometimes not - were only just beginning their careers, working for the state-sponsored news channel. They were saved a life of frustration when news on TV was soon freed of the government's hold.

Back then consumers of journalism complained about bad roads and poorly kept gardens in their neighbourhoods, and used words such as "apropos". Now they outrage against "biased journalists", and use expressions such as "facepalm". People who might review films live on Twitter now used to hire a video player and three or four VHS tapes and watch them all on one night - in a group, because that saved money. Getting a train ticket issued was no less an achievement than passing school exams.

Back then we didn't know of the internet. Back then, around the same time - it could be when you finally got that final Big Fun wicket to complete the collection of ten - a group of adventurers, in different parts of the world, driven by genius, a bit of craziness and a healthy disregard for Nostradamus, began working on one of the internet's biggest beneficiaries, Cricinfo.

Sidharth Monga is an assistant editor at ESPNcricinfo