Where's South Africa's next major fast bowler?

For a country where allrounders seem to be a dime a dozen, the number of quick bowlers ready for national duty are surprisingly thin on the ground

Firdose Moonda

31-Jul-2010

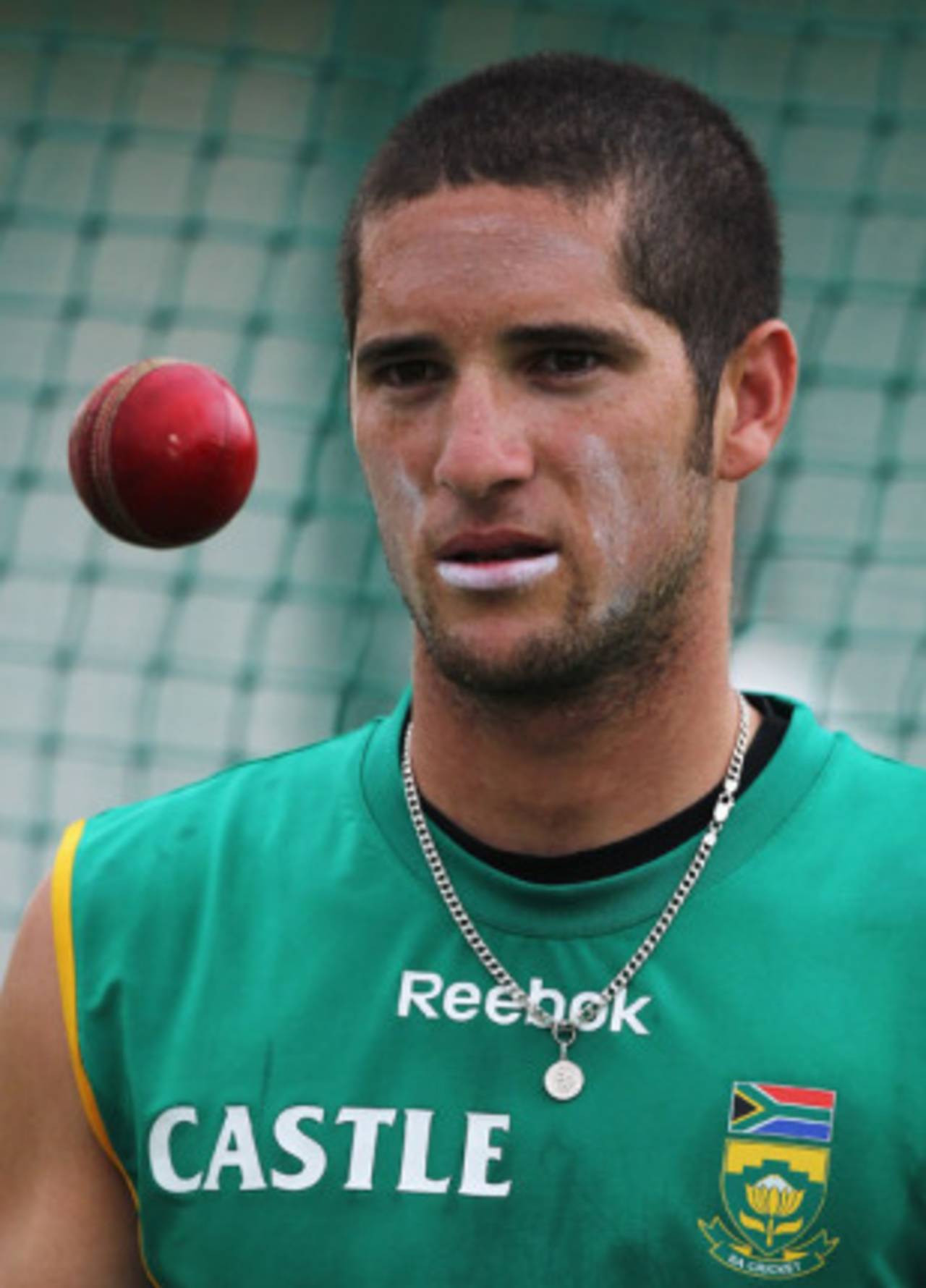

Parnell: after him, who? • Getty Images

March must seem a like very long time ago for Wayne Parnell. That's when he picked up a groin injury that initially sentenced him to six weeks on the sidelines. He had just been bought for $610,000 for the third season of the Indian Premier League by the Delhi Daredevils but was unable to vindicate his price tag. But while the GMR Group wouldn't have been happy to see their money spent on a player they couldn't use, Parnell's injury couldn't have come at a less disruptive time for the South African team. He was expected to return for their Caribbean crusade in May. That, though, didn't happen.

"I was misdiagnosed, so when the injury was reassessed, we found out that it was going to take longer to heal," Parnell told Cricinfo. It's been four months and Parnell is still on the mend, but what would have happened to the national team, if during Parnell's injury one from the dream pairing of Dale Steyn or Morne Morkel was also indisposed?

The only other upcoming player who has been identified as a genuine quick in the country is 24-year-old CJ de Villiers. It's possible he would have been fast-tracked onto the international stage. Else the administrators would have had to call on one of the fast-mediums or medium-fasts who have fallen off the assembly line of allrounders in recent times.

South Africa is awash in these two-in-one players and a quick scan of the franchises shows that the numbers are only growing.

"Cricketers like to be able to do both disciplines," explained national coach Corrie van Zyl. Former captain Shaun Pollock agreed: "With the way one-day cricket has developed, and the growth of Twenty20 cricket, more players want to contribute with both bat and ball. Players may also feel as though they always need to add something to their game and those who are not specialists may feel they can still hold down a place as an allrounder."

While that may reveal why multi-skilled cricketers are in abundance the world over, it doesn't explain why South Africa produces significantly more of the species than other countries.

"I would say that the conditions allow for this many allrounders to come through but that argument won't hold up because Australia has similar conditions and they have a lot more specialist fast bowlers. It must be a generational thing. Young players now want to be like Shaun Pollock. Before that they may have wanted to be like Brian McMillan and before that like Mike Procter," said Richard Pybus, former coach of Pakistan and currently in charge of the Cape Cobras franchise.

The preponderance of allrounders is one of the reasons South Africa are struggling to unearth more genuine fast bowlers to bolster their ranks. The only region with a wealth of fast-bowling talent is the Eastern Cape, where the Warriors franchise has nine pacemen on their books. They range from veterans like 33-year-old Garnett Kruger, who has played four matches for South Africa but is probably past his best, to young guns such as Siyamthanda Ntshona and Reece Williams.

It's the latter who show potential to grow into the next generation of South Africa quicks. For that to happen they need administrators with patience, as Pollock explained. "Genuine quicks are difficult to develop. The nature of cricket now is such that bowlers often have to play a containing role, and there's not as much opportunity as in the past to allow a young tearaway to just go wild." Time for development, though, is a luxury some teams can't afford.

"We have plenty of fast bowlers who can be just as effective in creating pressure. What we need now is for some of those to develop into genuine quicks, just like Allan Donald did," van Zyl said. "For that, they need to get more experience and build confidence. It would be nice to have one or two more who are almost ready to step onto the international stage, but we are realistic about finding them. Genuine quicks don't just fall out of trees."

And that's why reaction to Parnell when he first arrived was like that greeting the discovery of a golden apple that had tumbled off a branch. "When we find someone with that sort of genuine pace, it causes great excitement and we want to put him in every team," said van Zyl. "I went straight from school to the Under-19 side, the national academy, South Africa A and then the national side," Parnell confirmed. "It was non-stop for a long time and that may have resulted in the injury."

Overuse is a common problem because getting the balance between practice and rest is tricky. "There is a danger that if players under-bowl they are not conditioned and their bodies are not hardened for a match situation, but if they bowl too much, there is the risk of injury," explains Pybus.

Van Zyl said that Cricket South Africa has a plan in place to strike the correct balance. "We are adopting a new performance software programme at the end of August. It's a new athlete-monitoring system that will help us track details of a player's training. We are going to use this particularly for fast bowlers to ensure that we are not over-exposing them."

Zondeki: cautionary tale•Getty Images

The problem of excessive wear and tear has already cost South Africa at least two genuine fast bowlers. Monde Zondeki, who famously took a wicket with his first ball in international cricket, had a string of back and side injuries caused by his mixed action. He made his debut in 2002 and played just one Test match in 2003 before being sidelined for two years. He last represented South Africa in 2008.

Another former Test player, Mfuneko Ngam, readily admits that nutrition and bone-density deficiencies contributed to the premature end of his career, but also pinned some blame for his decline on over-training.

"I wanted to be faster than anyone else because I thought it was the only way I would get into the national team. I didn't want to just be bowling 140kph but over 150ph, and that meant I had to practise more. I also didn't listen to the advice of my coaches. They would tell me to only run on grass, but I would go for runs on tar roads. Sometimes after training, I wouldn't feel tired out, so I would run an extra five kilometres just to feel as though I had worked enough."

Ngam played just three Test matches, and took 11 wickets, before being hit by a barrage of stress fractures. He now runs an academy, under the auspices of CSA, at the University of Fort Hare, for players of colour. While the academy caters to batsmen and bowlers, its initial mandate was to try and unearth the next Makhaya Ntini.

Ngam has found that the bowlers under his care have the same effervescent energy he once had. "They want to bowl all day and I have to tell them to stop. Quick bowlers really need to have enough access to information to know how to take care of their bodies," Ngam said.

The new approach from CSA should counter that problem, although it will take the individual bowlers themselves to put into practice what they learn. Parnell, for one, doesn't want to change too much of his action because "it got me where I was". He admits that a smoother action, "more like Steyn's" may provide him with a buffer against further injury, but says his own "slightly awkward" action is what gets him wickets.

Parnell has returned to the gym and said he is taking "baby steps" to making a comeback. On Twitter he revealed that he is leg-pressing 10 kilograms and benching five. He aims to be back for the domestic season, starting in September. If he isn't, it will be interesting to see who the back-up fast bowler for the national team will be.

Firdose Moonda is a freelance writer based in Johannesburg