Literary cricketers

All the field's a stage

James Runcie

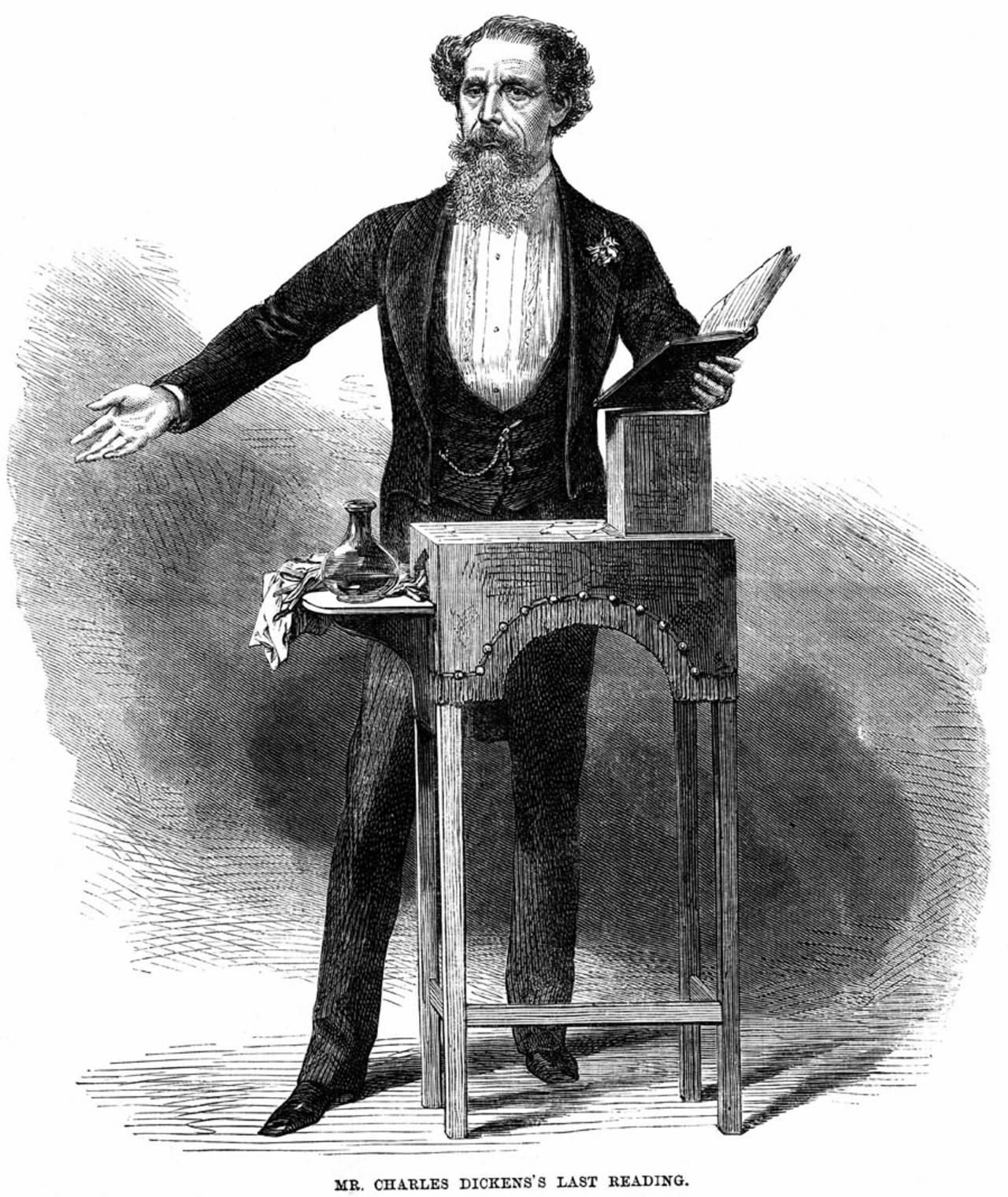

Charles Dickens gives a public reading • Getty Images

Cricket contains multitudes. The players are, in the words of Polonius from Hamlet, "the best actors in the world, either for tragedy, comedy, history, pastoral, pastoral-comical, historical-pastoral, tragical-historical, tragical-comical-historical-pastoral, scene undividable, or poem unlimited". The game is certainly Shakespearean. Ben Stokes's roar of victory in the Third Ashes Test of 2019 was pure Henry V. Headingley was Agincourt, the flags of St George were flying, Stokes was the young warrior king, with Jack Leach his cousin Westmoreland:

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he today that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne'er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition:

And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here

Test matches can be epic five-day events following a traditional five-act structure. The county equivalent, the Championship, once a three-act play, has lost out to more abridged and lucrative rivals. Twenty20 is perhaps the equivalent of a short story. Sometimes it's Hemingway, sometimes it's Chekhov - and sometimes you wonder why you bothered. It's tempting to imagine writers casting cricketers as their central characters: men and women who stride out of the pavilion and on to the page. Who would be their epic warriors, their romantic heroes, their improbable villains and their lovable rogues? And, if you are a cricketer, which writer would best describe you? You might see yourself as a swashbuckling hero from The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas, a veritable d'Artagnan with the bat, only to be run out in a Feydeau farce. It is easier for players who are legends already. Here is Sir Arthur Conan Doyle on W. G. Grace, in his Reminiscence of Cricket:

A statue from Thebes or from Knossos,

A Hercules shrouded in white,

Assyrian bull-like colossus,

He stands in his might.

But if WG is Hercules, which other gods and heroes would play in his team? Homer's Iliad is a good enough place to start. Who are the Agamemnons, the Hectors and the Apollos of the cricket field? The tall and mighty bowlers Joel Garner (6ft 8in) and Curtly Ambrose (6ft 7in) could form a terrifying opening pair, "breathing aggression" like "the incomparable Glaucus" and the Trojan hero Hector, who "hurled himself into the struggle of men like a high-blown storm cloud". Imagine "far-striking Apollo" as the big-hitting Rohit Sharma, "powerful Agamemnon" as Javed Miandad, "the huge and the mighty" Tlepolemus as Inzamam-ul-Haq, and then Pherecles, as "brilliant with his hands" as Sachin Tendulkar.

Menelaus ("master of the great war cry") finds his cricketing equivalent in Lancashire's George Duckworth, the wicketkeeper known in his day for having the loudest appeal in the game. Aeneas ("raging to cut down any man who might come to face him") is Dennis Lillee and, when one reads of Ajax the Swift ("a small man armoured in linen with a throw… that surpassed all Achaians and Hellenes") it is hard not to think of Jonty Rhodes.

The central drama of The Iliad rests with "fleet-footed" Achilles, "the most terrifying of all men", who is brilliant, angry and unpredictable, spending much of the epic sulking in his tent while the Trojans put his colleagues to the sword. In an article for The Nightwatchman, Tom Holland discovered the cricketing equivalent of Achilles in Kevin Pietersen, who returns to battle from the tent of resentment after his text-message imbroglio, scoring 186 to set up England's victory over India in the Second Test at Mumbai in 2012-13. Homer would have admired his footwork, and might even have said: "This man has gone clean berserk so that no one can match his war craft against him."

KP completes an Iliad XI of epic warriors. The history of cricket has its real war heroes too, none more than England and Yorkshire's Hedley Verity, one of Wisden's Cricketers of the Year in 1932, a left-arm spinner who once took 14 Australian wickets in a day. He died of wounds sustained during the Allied invasion of Sicily in 1943. His last order to his troops was to "keep going". Such heroism could have come straight from the pages of Tolstoy's War and Peace, where Prince Andrei hears a similar instruction at the Battle of Austerlitz: "Keep going! Don't drag your feet." For Andrei, the intensity of the fight, and the need for glory and the respect of his fellow men, drown out any other consideration. "It's the only thing I want, the only thing I live for… Death, wounds, loss of family, nothing frightens me. And however near and dear many people are to me, my father, my sister, my wife - the dearest people to me - but, however terrible and unnatural it seems, I'd give them all now for a moment of glory, of triumph over people, for love from people I don't know and will never know, for the love of these people here."

The thirst for glory obliterates all other concerns. How can one achieve this? Tolstoy believed "the two most powerful warriors are patience and time". If that is the case, the most Tolstoyan of cricketers are those who "keep going": Hanif Mohammad (337 in 970 minutes for Pakistan against West Indies in 1957-58), Gary Kirsten (275 in 878 for South Africa against England in 1999-2000) and Alastair Cook (263 in 836 for England against Pakistan in 2015-16). Cook's other life, as a Bedfordshire sheep farmer, would not, however, have appealed to Tolstoy the vegetarian. Indeed, his current profession as a good-looking country squire suggests he's come from the pages of another novelist.

Jane Austen - who herself had a strong family link to cricket - was a great believer in the importance of etiquette: "Manners is what holds a society together. At bottom, propriety is concern for other people. When that goes out the window, the gates of hell are shortly opened, and ignorance is king." Who else might be the Austen cricketers, the romantic heroes who play by the rules with style, generosity and sportsmanship? Opening with Cook is India's most charming man, Rahul Dravid. Kane Williamson, who embodied grace and decency after New Zealand's defeat in the 2019 World Cup final, is captain and No. 3. Australia's accomplished Michael Hussey is next, followed by South Africa's dignified Hashim Amla, and the unflappable New Zealander Stephen Fleming. The Austen wicketkeeper must surely be the charismatic Adam Gilchrist, who adds a touch of dash and thrill, and famously walked when he knew he was out. The seamers are Sir Richard Hadlee, known not only for his talents as an all-rounder but for his formidable charity work, and Brett Lee, who would also provide the post-match entertainment with his band, Six and Out. The spinners are Anil Kumble, respected for his patience, grit and calm, and the courteous Muttiah Muralitharan.

These men may be the saints, but what about the sinners? What if Austen's XI were to face a team of less honourable players, whose crimes against the spirit of cricket might come to the attention of a fictional detective? Conan Doyle's hero Sherlock Holmes in part takes his name from cricket: "Holmes was homely," he wrote in The New York Herald, "and as for 'Sherlock' - well, years ago I made 30 runs against a bowler by the name of Sherlock, and I always had a kindly feeling for that name." Conan Doyle took part in 449 matches, ten of them first-class, and shared the field several times with P. G. Wodehouse, J. M. Barrie and W. G. Grace. So it's tempting to think of a Holmes XI, with suspicions attached. The openers would be England's Douglas Jardine (Bodyline) and New Zealand's Lou Vincent (match-fixing), followed by Steve Smith (sandpaper specialist, and skipper), then Greg and Trevor Chappell (underarm bowling), Hansie Cronje (taking bribes), and wicketkeeper Brendan Taylor (more bribes, plus cocaine). Following them are Vizzy, the Maharajkumar of Vizianagram (offered a player a gold watch to run out another), Suraj Randiv (deliberate no-ball to deny Virender Sehwag a hundred), Mohammad Amir (more no-ball controversy) and Vinoo Mankad (you know why). The team have their own umpire, Darrell Hair, and Conan Doyle might ensure he is paired with Chris Watts, both a first-class umpire and a retired detective.

Cricket, however, is not simply a binary game filled with heroes and villains. It has a cast of characters who are dynamic, mercurial and even lunatic. They are men who like to ensure they are in bed at least by breakfast on the day of the match, and who find fielding dull: in August 1893, Australia's Arthur Coningham was so cold at a touring game in Blackpool he gathered straw and twigs to start a fire in the outfield; Colin Ingleby-Mackenzie, who led Hampshire to the 1961 Championship, and once persuaded an umpire to take a radio on to the pitch so he could check the racing results; and Somerset's Arthur Wellard who, fielding at silly mid-off, would remove his false teeth to unsettle the batsman. Such players embody what Charles Dickens called "the eccentricities of genius".

Dickens adored cricket, and scatters references through Barnaby Rudge, Great Expectations and Martin Chuzzlewit. In The Old Curiosity Shop, a child dies with a bat leaning against his bed. James Steerforth, the captivating friend of David Copperfield, is described as "the best cricketer you ever saw", which is a terrible smokescreen - and a prelude to his revelation as a cad and a bounder. Dickens's first novel, The Pickwick Papers, contains an account of a match between All-Muggleton and Dingley Dell, supposedly based on a real fixture between Cobham and Town Malling, played sometime between 1830 and 1835. In the novel, Mr Jingle describes playing in the West Indies, a piece of reportage surely about to be banned in every American library: Warm! - red hot - scorching - glowing. Played a match once - single wicket - friend the colonel - Sir Thomas Blazo - who should get the greatest number of runs. Won the toss - first innings - seven o'clock a.m. - six natives to look out - went in; kept in - heat intense - natives all fainted - taken away - fresh half-dozen ordered - fainted also - Blazo bowling - supported by two natives - couldn't bowl me out - fainted too - cleared away the colonel - wouldn't give in - faithful attendant - Quanko Samba - last man left - sun so hot, bat in blisters, ball scorched brown - 570 runs - rather exhausted - Quanko mustered up last remaining strength - bowled me out - had a bath, and went out to dinner.

A Dickens XI would be full of larger-than-life characters moulded in the manner of Alfred Jingle. It would be a team of bar-emptying talent: the stylish, the boisterous, the unpredictable and the glorious. Chris Gayle and David Warner open the batting, ahead of Don Bradman, Viv Richards and Garry Sobers. Ian Botham comes next, with Keith Miller at No. 7. Godfrey Evans is behind the stumps (and, afterwards, behind the bar at his pub, The Jolly Drover). Merv Hughes and Fred Trueman provide the pace attack and Shane Warne the guile. Pit this team against the Holmes XI, and "the game's afoot".

Towards the end of his life, Dickens received a visit from an American who had heard he was in a critical state of health. Dickens assured him this was not the case. In fact, he was in what he called a "cricketing" state of health: his days were full of interest, curiosity, engagement and excitement, as he waited expectantly for the next ball of life to be bowled, the next blow to be struck, the next catch to be taken. For a cricket lover, there are always more tales to tell, of character and conflict, of epic drama, hope and heroism. Anything can happen before stumps.

James Runcie is the author of The Grantchester Mysteries. His grandfather J. W. C. Turner played for Worcestershire.