A cricket story run out by indifference

Aravind Adiga's new novel is centred on the game but isn't really in love with it

Karthik Krishnaswamy

22-Oct-2016

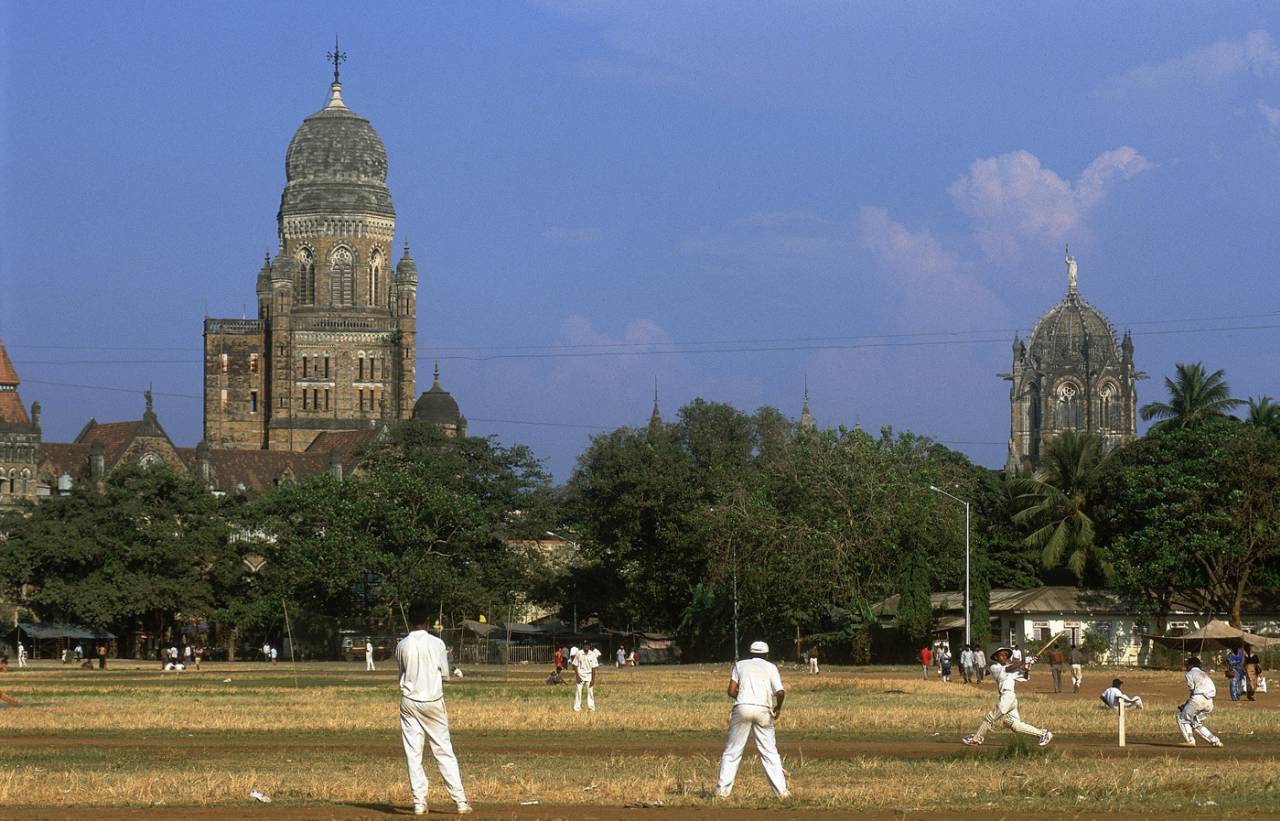

Do many people involved in cricket simply see it as a way to better means? • Getty Images

The first time we see Manjunath Kumar, the schoolboy hero of Aravind Adiga's Selection Day, at the crease, he is batting with a hairline fracture in his left thumb. He bats through the pain, bats for over an hour, overtakes his older brother's score, and does all this in front of a selector.

This, perhaps, is Adiga's nod to the story of Eklavya in the Mahabharata. In exchange for taking the self-taught archer Eklavya under his tutelage, Dronacharya, who instructs the princes of Hastinapura in the art of warfare, asks that the boy cut off his right thumb. Eklavya obliges.

Adiga does not reveal how Manju came to break his thumb, but his mentor, the talent scout Tommy Sir, concludes that his father Mohan Kumar must have been behind it.

"Would I do that to my own son?" Mohan wails. "My own Robusta?"

Before he came to Mumbai, Mohan worked in a coffee plantation in the Alur district of Karnataka, earning three-and-a-half rupees a day. "There he cleared twigs, dropped sunna from his forefingers in white circles around the plants, and watered the bushes, taking more care of the Arabica, and less care of the Robusta."

Mohan's older son Radha Krishna Kumar is the Arabica to Manju's Robusta. Radha has a "secret blessing" from the family deity and a batting glove given him by Sachin Tendulkar. Manju, younger by a year, doesn't have either. Mohan drives both of them, in idiosyncratically abusive ways, to focus on their cricket to the exclusion of everything else - including shaving, "because the cut of a razor makes hormones run faster in his blood", and driving cars - but makes it quite clear which one will become the world's best batsman and which one the second-best.

Adiga is never far from making a pronouncement, about matters ranging from revenge - "the capitalism of the poor" - to what Indians want in literature - "We want to see ourselves depicted as soulful, sensitive, profound, valorous, wounded, tolerant and funny beings. All that Jhumpa Lahiri stuff"

The world, however, writes its own scripts. Radha's batting declines; he has a growth spurt and develops a "weight-transfer problem". Manju, short, compact, with "a way of deflecting everything off his pads", continues to hoard runs. Around halfway into the novel, Manju breaks Radha's record for the highest score ever made by a Mumbai schoolboy. When his school funds him to spend six weeks playing cricket in England, Mohan tells Manju he has taken what is "rightfully [his] elder brother's".

It's the stuff of Bollywood, and it's only one thread in a crowded plot in which Adiga uses cricket as a springboard to critique the ills of 21st-century India.

The old guard that nourished Mumbai's cricketing grassroots, embodied in Tommy Sir, is losing its grip on the game and handing it over, resignedly, to the forces of neoliberalism represented by Anand Mehta, who has no love for cricket but knows it can make him a lot of money.

Urged on by Tommy Sir, Mehta agrees to sponsor Radha and Manju, enabling the family to move from a slum in Dahisar to an apartment in Chembur, but in exchange for this, he extracts from Mohan the promise of a share of his sons' future earnings.

Not yet 14, Manju's life is now defined by cricket just when he is beginning to feel ambivalent about the sport. At the crease, his superstitions include reciting a poem taught him by his mother, whose whereabouts are unknown and who may well have run away because of her husband's violence. That violent man's violent obsession is also responsible, in some part, for Manju's success at the crease; perhaps recognising this, he breaks his bat in two after smashing the Mumbai schoolboy record.

Manju has other interests - science, CSI Las Vegas - and wants to go to junior college after finishing his tenth standard, but both his father and Tommy Sir are against the idea. He is also coming to terms with his nascent sexuality, which his friends and brother, now bitterly antagonistic, are keener to label than he is: he becomes the target of innuendo on one hand and well-meaning but patronising support on the other.

HarperCollins

Running away from all this, Manju takes refuge in his friendship with - and repressed attraction towards - his wealthy, worldly team-mate Javed Ansari, who writes poetry, denounces cricket for becoming overrun by corporates - "Tatas batting, Reliance bowling" - and, allowed to do so by his class privileges, openly expresses his homosexuality while taunting Manju for being a "slave", to his father, to Tommy Sir, to cricket.

Tugged from all sides by various self-interests, which way will Manju go, and how much of a choice will he have in the matter? What of Radha? Adiga navigates the plot to what could well be an excellent open-ended finish, until you realise it isn't quite over yet. There remain 17 pages of an entirely unnecessary "Part Two" that spells out exactly what the brothers' respective places are in a dystopian future where the IPL and the "Celebrity League" have cannibalised cricket almost entirely.

It's the final flourish of the novel's two least endearing qualities. The first is Adiga's endlessly invasive authorial voice. Whether he shoots them from the shoulder of one of his characters - most frequently Tommy Sir, Mehta and Ansari - or slips them in while moving the plot forward, Adiga is never far from making a pronouncement, about matters ranging from revenge - "the capitalism of the poor" - to what Indians want in literature - "We want to see ourselves depicted as soulful, sensitive, profound, valorous, wounded, tolerant and funny beings. All that Jhumpa Lahiri stuff."

The second is a persistent disdain for cricket. It's hard to say if anyone in the novel likes the game. Even at the school level, everyone swept into involvement with it seems to view it only as a vehicle for something "bigger": a way out of poverty, a tool of vicarious ambition, a means to humiliate the less talented, an avenue for financial speculation.

Adiga piles Selection Day with tall scores, but never once describes a contest between two teams or between a bowler and a batsman. This is only schools cricket, but anyone who has watched or played the game at any level knows it can transcend its surroundings and its immediate context and become something vital, beautiful and life-affirming. This never happens, and is never allowed to happen, in Selection Day. Adiga treats cricket like he treats his characters, making it speak for him while barely letting it speak for itself.

Selection Day*

By Aravind Adiga

HarperCollins India

292 pages

Rs 599

By Aravind Adiga

HarperCollins India

292 pages

Rs 599

*October 24, 7.47GMT: Book details changed to reflect the Indian edition

Karthik Krishnaswamy is a senior sub-editor at ESPNcricinfo