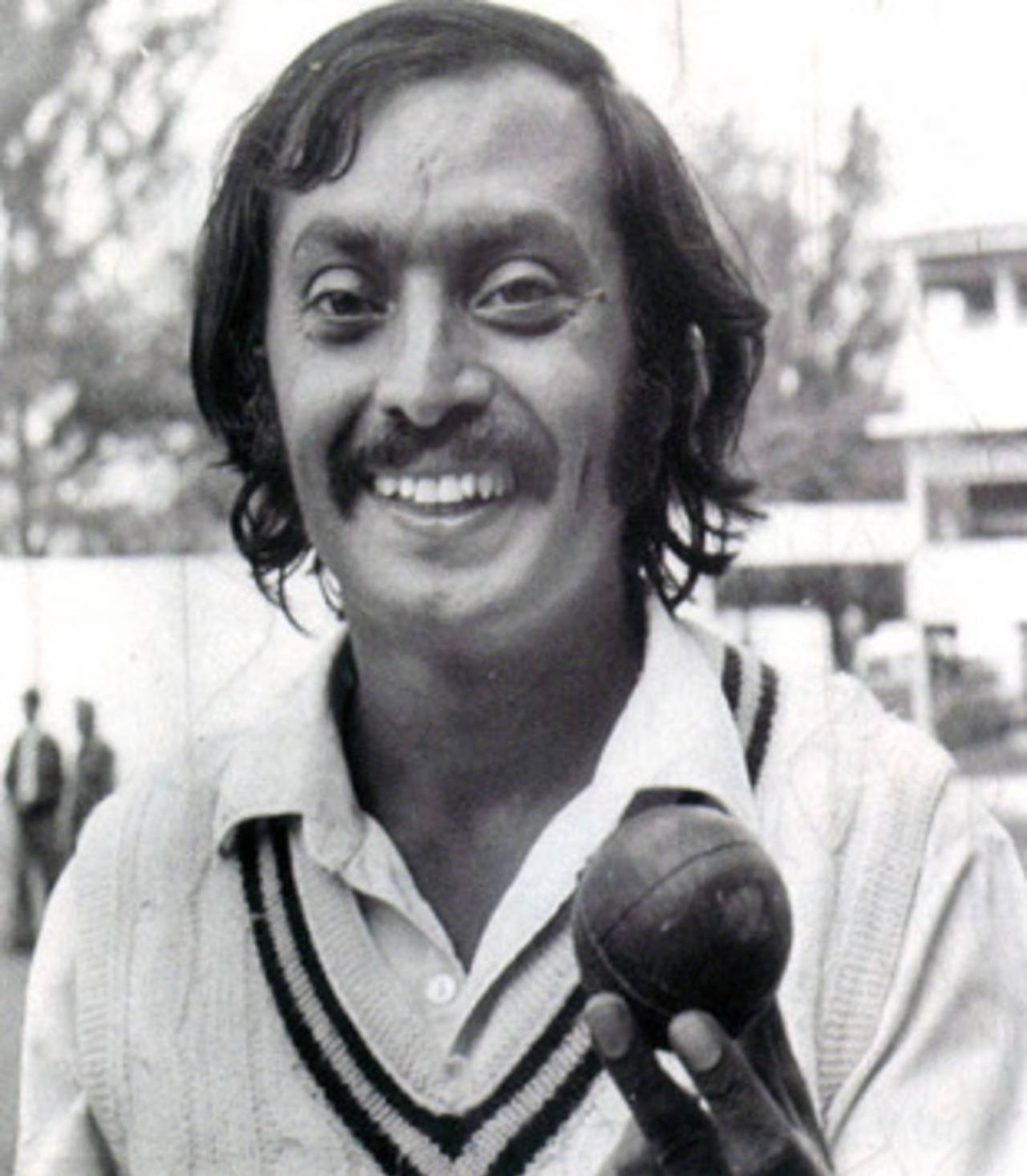

Ismail "Baboo" Ebrahim's story could be that of any non-white South African cricket in the apartheid era. Except that, by all available accounts, he was not just

any non-white cricketer.

Wisden says he would have been a star in "any first-class arena". Craig Marais, former Boland wicketkeeper and now a commentator, remembers how Ian Chappell said Ebrahim was better than any white spinner in the country. Brett Proctor, who played with Ebrahim and is now Kingsmead's ground manager, says Ebrahim "may have made it to international level, given the right opportunities". However, the sixties and seventies were not times for opportunity: even the 48 first-class matches that Ebrahim managed came after struggle, though they left memories to last a lifetime.

In January 1957, when watching from the small non-whites section at Kingsmead ("Couldn't go anywhere else"), 11-year-old Ebrahim saw Johnny Wardle bowl Roy McLean through the gap between bat and pad with a chinaman. "That's when I said, 'This is what I am going to do. This is what I am going to be.'"

A left-arm spinner he became, and like Wardle, chinamans he bowled. When he grew slightly older, he came to know of a Natal team being picked for a match in Cape Town. "I said, 'Wow, cricket can make me see the world.' And I said I was going to be good, I was going to see the world."

Ebrahim was slightly fortunate in that the boards representing coloured, Indian and black cricketers had unified to form the South African Cricket Board of Control (SACBOC), thus ending the era of segregated cricket. Still, non-whites could only play on torn matting wickets, where a delivery could hit you in the head and the next one on the ankle. The outfields were bumpy, the equipment substandard. And even with the boards unified, all the players could manage was three games a year. They didn't have the money to play more than that.

Cricket, at least on paper, was somewhat welcoming, but society wasn't. When Australia travelled here for what would be South Africa's last series before isolation, Ebrahim was at Kingsmead to watch them practise. "I asked them if I could bowl," remembers Ebrahim. "And one of them said, 'Yes, let him bowl.' Security steps in and says, 'No he can't bowl. He is black.' But they insisted that I bowl. I remember bowling Ian Redpath in the nets, and suddenly it was a case of 'Who are you, my boy?' and this that and so forth. And to this day, Ashley Mallett, whenever he comes to South Africa, still remembers me."

As the leaders of the community fought for independence, the cricketers went about their own quiet struggle. Ebrahim, Omar Henry and a few others decided to test the white clubs' promise that they were open to any cricketer who merited a place. "Omar joined a club in Cape Town, I joined a club in Durban, Tiffy Barnes in Jo'burg.

"They were always saying that they were open to everybody. And we said, 'Let's test it.' We joined them. At first it was a case of the dressing room. We said, 'No, we want to get into the pub as well.' You must have heard of incidents when restaurants didn't want to serve us guys, and we kicked the table and walked out.

"I remember the third game I played for the white club, I got 10 wickets in an innings, and they insisted that I come to the pub," Ebrahim says. "I said, 'I don't drink, I am sorry.' They asked me to just come in and have a Coke. So I thought I'd have a Coke. And there were some people who didn't like the idea, and the guys told them, 'If you like it, stay around. If you don't like it, you can go away. This person and we are staying here.' That's how we started breaking apartheid."

Proctor remembers Ebrahim as a bowler who was quick through the air but also someone who turned the ball, and "never gave anything away". "To be fair to him, he played on green tracks in Durban, and the thing to do in South Africa then was to bowl as fast as you could." Proctor says. "To wonder if he would have played ahead of Alan Kourie [Transvaal's left-arm spinner, whose career span was roughly the same as Ebrahim's] is a question similar to debating how good Barry Richards was. But both could have made it to international cricket at that time."

Neither of them managed that in the end because of isolation, but Kourie did have a first-class career that lasted 127 games to Ebrahim's 48. Ebrahim rates Denys Hobson, the former Western Province legspinner, higher. Chappell probably saw Ebrahim on the International Wanderers tour in 1975-76, when he got just one game,

in Durban, and didn't even get to bowl in the first innings. In the second, he ran through the visitors with 6 for 66.

Ebrahim found the Lancashire League more welcoming. "It was professional," he says. "If you didn't produce results, they told you in no uncertain terms. Those days were different. You must remember, many Test cricketers played in the leagues. And the toughest league was the Lancashire League. You had one professional in each team, one of the top guys from world cricket, to draw the crowds from that area, but on the side they had three-four other Test players who played as amateurs, who were just as good.

"Security steps in and says, 'No he can't bowl. He is black.' But they insisted that I bowl. I remember bowling Ian Redpath in the nets, and suddenly it was a case of 'Who are you, my boy?' And to this day, Ashley Mallett, whenever he comes to South Africa, still remembers me"

"When I went there I was already 30-plus, and couldn't tell them that I was that age. Took off a couple of years, acted a bit younger. I was much skinnier, fitter. After all, I had to take the place of one of the great cricketers of the world, Garry Sobers."

It was here that Sulaiman "Dik" Abed took 100 wickets and scored more 1000 runs in a season on more than one occasion. Unlike Ebrahim, though, Abed never managed to play first-class cricket. There were others too who missed out. "I don't think I will go into names," Ebrahim says. "At the time the bodies [non-coloured ones] got together and got cricket going, we had a lot of good cricketers.

"The only way you judge them is by who they played against. One cannot just judge playing one-two games, which is all they got then. Coming from matting to turf was a big challenge for our boys. Unless you play it, you have no idea of the difference. We didn't even know how to doctor a wicket. We only learned it afterwards. Where did I learn it? Playing in the Lancashire League. Home game, make a wicket that suits your spinner. Matting was the same thing for both sides. Only given the opportunity did we learn these things. You don't know where those guys would have been."

Now, at 64, Ebrahim is a respected figure in Durban cricket. His son has coached Kwazulu-Natal. Ebrahim says he doesn't feel much bitterness when he looks back. "As you got older, you get wiser," he says. "So many other things come into the equation. Thank almighty. Through cricket he has made me see a lot of places, meet a lot of people. I thank god for that." That happened mainly through the Lancashire Leagues, and Masters events, where he finally got to represent South Africa, and where, as he proudly mentions, he got Viv Richards and Gordon Greenidge out

in the same game.

And he always has happy memories to fall back upon. Like this story.

"Rohan Kanhai used to play for Transvaal. Rohan Kanhai, the great West Indian. The ground is packed and a lot of people have come to see Kanhai. And in the second innings - there were about two hours - we made a declaration to see if Kanhai wanted to have a go. They tossed me the ball. 'Bowl to him.' I told him, 'Kanhaiya bhai, main upar se daloonga [I'll toss them up for you].' He was finding it difficult to hit the ball because I was turning it so much. The more air I gave, the more it bit [the surface]. And after a couple of balls he comes down the wicket and he tells me, 'Eh, sala bhai mere ko dekhne aaye hain, tere ko nahi dekhne aaye hain [They have come to watch me, not you].' These are the small things that happen in cricket, and then you look back and say, 'What a wonderful experience.'"

Sidharth Monga is an assistant editor at ESPNcricinfo