That can't be legal

Cricketers who have - by accident or design - led to changes in the Laws

Steven Lynch

15-Apr-2013

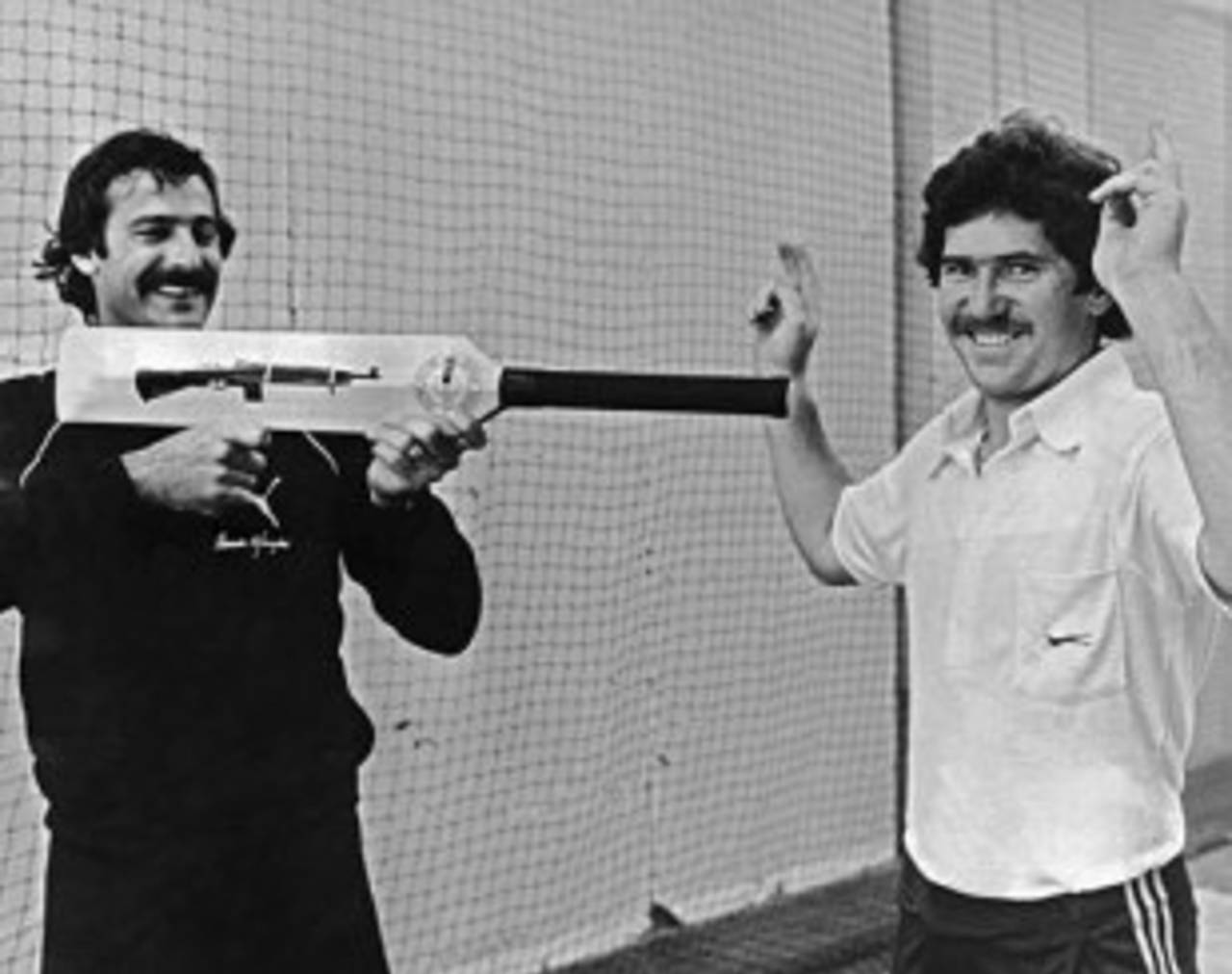

Dennis Lillee's aluminium bat didn't resonate with the lawmakers • Adrian Murrell/Getty Images

Steven Finn

The inspiration for this article came in the frequent collisions between the England fast bowler Finn's knee and the stumps, which have cost him a couple of wickets in the past year, originally after Graeme Smith complained that the habit was distracting. The umpires started to call dead ball when it happened, but that occasionally penalised the batsmen too: now a rule change means that no-ball will be called, meaning the batsman can still score runs but can't be out. Finn, who has worked over the winter to try to iron out the flaw, isn't too worried: "As long as it's named after me I don't mind!"

The inspiration for this article came in the frequent collisions between the England fast bowler Finn's knee and the stumps, which have cost him a couple of wickets in the past year, originally after Graeme Smith complained that the habit was distracting. The umpires started to call dead ball when it happened, but that occasionally penalised the batsmen too: now a rule change means that no-ball will be called, meaning the batsman can still score runs but can't be out. Finn, who has worked over the winter to try to iron out the flaw, isn't too worried: "As long as it's named after me I don't mind!"

Thomas White

One of the most rapid rule changes happened in 1771 after White of Reigate - not for nothing known as "Shock" - came out to the crease with a bat as wide as the stumps, which meant he was exceedingly unlikely to get bowled out. The Hambledon club, the game's pre-eminent organisation at the time, passed an immediate rule restricting the width to 4¼ inches, which remains the limit today. In a humorous incident in 1884, WG Grace suspected that some of the bats being used by the Australian tourists were too wide, and asked for them to be measured. They were found to be fine - but when one of WG's own blades was tested, in a tit-for-tat measure, it turned out to be too big.

One of the most rapid rule changes happened in 1771 after White of Reigate - not for nothing known as "Shock" - came out to the crease with a bat as wide as the stumps, which meant he was exceedingly unlikely to get bowled out. The Hambledon club, the game's pre-eminent organisation at the time, passed an immediate rule restricting the width to 4¼ inches, which remains the limit today. In a humorous incident in 1884, WG Grace suspected that some of the bats being used by the Australian tourists were too wide, and asked for them to be measured. They were found to be fine - but when one of WG's own blades was tested, in a tit-for-tat measure, it turned out to be too big.

Dennis Lillee

Sticking with bats, in 1979-80, Lillee famously went out in a Test against England in Perth with an aluminium one. After a few clunks of leather on metal, England's captain, Mike Brearley, complained that the ball was being damaged, and Lillee was ordered to change the bat - which he eventually did, after a rather theatrical argument with his captain (Lillee had an interest in the company that made the "ComBat"). Not long afterwards, MCC issued a new redraft of the Laws, one of which stated that the bat had to be made of wood.

Sticking with bats, in 1979-80, Lillee famously went out in a Test against England in Perth with an aluminium one. After a few clunks of leather on metal, England's captain, Mike Brearley, complained that the ball was being damaged, and Lillee was ordered to change the bat - which he eventually did, after a rather theatrical argument with his captain (Lillee had an interest in the company that made the "ComBat"). Not long afterwards, MCC issued a new redraft of the Laws, one of which stated that the bat had to be made of wood.

Muttiah Muralitharan

Murali's wrist-popping bowling action has inspired millions of words and, it seems, almost as many biometric tests, during which the elbow he was suspected of flexing was sometimes encased in plaster. The upshot of all the electronic wizardry was that the ICC was forced to reconsider the rules about throwing, since the findings showed that almost all bowlers bend their elbow - previously considered to be the sign of a thrower - to some degree. An arbitrary limit of 15 degrees of elbow flex, beyond which the bending is apparently obvious to the naked eye, was introduced.

Murali's wrist-popping bowling action has inspired millions of words and, it seems, almost as many biometric tests, during which the elbow he was suspected of flexing was sometimes encased in plaster. The upshot of all the electronic wizardry was that the ICC was forced to reconsider the rules about throwing, since the findings showed that almost all bowlers bend their elbow - previously considered to be the sign of a thrower - to some degree. An arbitrary limit of 15 degrees of elbow flex, beyond which the bending is apparently obvious to the naked eye, was introduced.

Harold Larwood

One of the upshots of the bad-tempered 1932-33 Bodyline series - in which the England fast bowlers sent down persistent bouncers, with a packed leg-side field - was an eventual restriction of the number of fielders on that side of the wicket (only two are allowed behind square now, and for a while no more than five were permitted in total). It's a bit unfair to name and shame Larwood for this - he was following his captain's instructions, and was fast enough (and accurate enough) to make the tactic work.

One of the upshots of the bad-tempered 1932-33 Bodyline series - in which the England fast bowlers sent down persistent bouncers, with a packed leg-side field - was an eventual restriction of the number of fielders on that side of the wicket (only two are allowed behind square now, and for a while no more than five were permitted in total). It's a bit unfair to name and shame Larwood for this - he was following his captain's instructions, and was fast enough (and accurate enough) to make the tactic work.

Lumpy Stevens

In the earliest days of organised cricket there were only two stumps, six inches apart. Stevens, from Woking, was one of the earliest star bowlers, helped by the fact that the first official set of laws, in 1744, allowed the fielding side to choose exactly where they wanted to mark out the pitch, within a 30-yard area. Stevens got his nickname from his habit of selecting a handy undulation to bowl over: a contemporary poem explained that "Honest Lumpy did allow/He could not pitch but o'er a brow." But Lumpy was deadly accurate, and in 1775 whistled three balls in quick succession between a noted batsman's stumps without dislodging the single bail. A middle stump was added shortly afterwards.

In the earliest days of organised cricket there were only two stumps, six inches apart. Stevens, from Woking, was one of the earliest star bowlers, helped by the fact that the first official set of laws, in 1744, allowed the fielding side to choose exactly where they wanted to mark out the pitch, within a 30-yard area. Stevens got his nickname from his habit of selecting a handy undulation to bowl over: a contemporary poem explained that "Honest Lumpy did allow/He could not pitch but o'er a brow." But Lumpy was deadly accurate, and in 1775 whistled three balls in quick succession between a noted batsman's stumps without dislodging the single bail. A middle stump was added shortly afterwards.

Mike Brearley

One of the most innovative of captains, Brearley once stationed all his fielders - including the wicketkeeper, David Bairstow - on the boundary in the closing stages of a one-day international, making it almost impossible to score more than a single from any particular delivery. Soon afterwards fielding circles - already a familiar sight in Australian domestic cricket - were made mandatory in international games too, ensuring that a certain number of fielders would be closer in. Brearley was also among the first to try a form of batting helmet, protecting his temples with a sort of skull-cap before full helmets became the norm around 1980.

One of the most innovative of captains, Brearley once stationed all his fielders - including the wicketkeeper, David Bairstow - on the boundary in the closing stages of a one-day international, making it almost impossible to score more than a single from any particular delivery. Soon afterwards fielding circles - already a familiar sight in Australian domestic cricket - were made mandatory in international games too, ensuring that a certain number of fielders would be closer in. Brearley was also among the first to try a form of batting helmet, protecting his temples with a sort of skull-cap before full helmets became the norm around 1980.

Phil Edmonds

In concert with his Middlesex captain Brearley (above), Edmonds devised a scheme to entrap some docile Yorkshire batsmen in a county match at Lord's in 1980. They placed a spare fielding helmet on the ground at short midwicket, to try to tempt the striker to play across the line to Edmonds' left-arm spin in order to collect the five penalty runs he would receive if the ball hit the helmet. Shortly afterwards the regulations were amended so the spare helmet could only be parked behind the wicketkeeper.

In concert with his Middlesex captain Brearley (above), Edmonds devised a scheme to entrap some docile Yorkshire batsmen in a county match at Lord's in 1980. They placed a spare fielding helmet on the ground at short midwicket, to try to tempt the striker to play across the line to Edmonds' left-arm spin in order to collect the five penalty runs he would receive if the ball hit the helmet. Shortly afterwards the regulations were amended so the spare helmet could only be parked behind the wicketkeeper.

Ray Lindwall's dragging back foot prompted the authorities to change the no-ball law•Hulton Archive

John Willes

In cricket's early days all the bowling was underarm, but this kept the pace of the ball down. Willes, from Kent, was one of several who began experimenting with a more roundarm delivery - suggested to him, legend has it, when his sister found it impossible to bowl properly because of her voluminous skirts (although this idea is generally discounted now). In 1822, Willes used his "new" method in a match at Lord's and was no-balled: according to the historian HS Altham, he "threw the ball down in disgust, jumped on his horse, and rode away out of Lord's and out of cricket history". However, the method soon won widespread acceptance - and eventually bowling with the hand above the shoulder was accepted too.

In cricket's early days all the bowling was underarm, but this kept the pace of the ball down. Willes, from Kent, was one of several who began experimenting with a more roundarm delivery - suggested to him, legend has it, when his sister found it impossible to bowl properly because of her voluminous skirts (although this idea is generally discounted now). In 1822, Willes used his "new" method in a match at Lord's and was no-balled: according to the historian HS Altham, he "threw the ball down in disgust, jumped on his horse, and rode away out of Lord's and out of cricket history". However, the method soon won widespread acceptance - and eventually bowling with the hand above the shoulder was accepted too.

Ray Lindwall

For years some fast bowlers had planted their back foot behind the crease but dragged it through and over the line. The no-ball law at the time allowed this, with the result that some bowlers were releasing the ball rather closer to the batsman than the prescribed 22 yards. It became almost an epidemic in the 1950s: Lindwall, the great Australian fast bowler, was by no means the only offender - but he was probably the most famous one. In the 1958-59 Ashes series the problem was compounded by some of the Aussie pacemen having suspect actions as well (not Lindwall, who jokingly described himself around this time as the last of the straight-arm bowlers). The giant Gordon Rorke, for example, dragged through the crease then let go what the English batsmen of the time considered to be blatant chucks. Eventually the law was changed so the front foot had to land behind the line: Don Bradman and Richie Benaud were vehement opponents of the change, but it remains in force today.

For years some fast bowlers had planted their back foot behind the crease but dragged it through and over the line. The no-ball law at the time allowed this, with the result that some bowlers were releasing the ball rather closer to the batsman than the prescribed 22 yards. It became almost an epidemic in the 1950s: Lindwall, the great Australian fast bowler, was by no means the only offender - but he was probably the most famous one. In the 1958-59 Ashes series the problem was compounded by some of the Aussie pacemen having suspect actions as well (not Lindwall, who jokingly described himself around this time as the last of the straight-arm bowlers). The giant Gordon Rorke, for example, dragged through the crease then let go what the English batsmen of the time considered to be blatant chucks. Eventually the law was changed so the front foot had to land behind the line: Don Bradman and Richie Benaud were vehement opponents of the change, but it remains in force today.

Wells and Shine

When the follow-on was first introduced, in 1835, it was compulsory if a side was a certain number of runs behind on first innings (originally 100 in a three-day game, but reduced to 80 in 1854). Occasionally, a team didn't really want to bowl again straightaway and resorted to giving away runs to let the opposition scrape past the follow-on score. In 1893, Cambridge's CM Wells bowled two deliberate wides to the boundary to ensure Oxford would not have to follow on in the Varsity Match at Lord's, and in the same fixture three years later EB Shine of Cambridge deliberately bowled three balls straight to the boundary. In 1900 MCC made the follow-on optional.

When the follow-on was first introduced, in 1835, it was compulsory if a side was a certain number of runs behind on first innings (originally 100 in a three-day game, but reduced to 80 in 1854). Occasionally, a team didn't really want to bowl again straightaway and resorted to giving away runs to let the opposition scrape past the follow-on score. In 1893, Cambridge's CM Wells bowled two deliberate wides to the boundary to ensure Oxford would not have to follow on in the Varsity Match at Lord's, and in the same fixture three years later EB Shine of Cambridge deliberately bowled three balls straight to the boundary. In 1900 MCC made the follow-on optional.

Steven Lynch is the editor of the Wisden Guide to International Cricket 2013