Dynamic and innovative, Packer will be remembered

Kerry Packer was an exception to the old adage that the first generation acquires, the second consolidates, the third squanders&

Gideon Haigh

28-Dec-2005

|

|

|

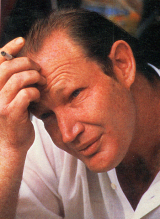

Kerry Packer was an exception to the old adage that the first generation acquires, the second consolidates, the third squanders. His grandfather Robert Clyde Packer was a journalist turned proprietor, his father Sir Frank a proprietor turned mogul; Kerry was a mogul turned symbol, his hulking figure, heavy jaw and harsh manner making him the most recognisable businessman of his generation. At his death, Australia's richest man controlled a fortune worth $US 5 billion; he had also just been deemed by Cricket Australia second only to Bradman in his influence on Australian cricket: a bouquet unthinkable when the main work towards it was done almost thirty years ago.

Very little about Packer's life, however, was predictable. Packer had a luckless childhood stricken by polio, a horrid education retarded by dyslexia, and a painful upbringing in which he was mocked and monstered by the tyrannous Sir Frank. He succeeded his father only because brother Clyde fled the family fold in 1972 after one dispute too many. But Kerry was very much his father's son. `He [Kerry Packer] was more politically opportunistic than Sir Frank and, although intensely loyal, more capable of unsentimental profiteering,' believes Dr Bridget Griffen-Foley of Macquarie University, whose The House of Packer (1994) charts the family's rise. `But although brutalised by his father, the pair also had much in common; the late Clyde Packer, by contrast, was more like his namesake and the family patriarch, Robert Clyde Packer.'

Kerry was not long in the job when he began reinvigorating Consolidated Press's television arm, the Nine Network, with a heady cocktail of sport, soaps and current affairs. All were solutions to the challenge of providing local content for new rules laid down by the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal, but the greatest of these was sport, of which Packer was obsessively fond, especially golf, rugby, horse racing and later polo.

Cricket, however, was the white whale to his Ahab. He was endlessly frustrated in his pursuit by the cosiness of relations between the Australian Cricket Board and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, and let it show in perhaps his most famous remark, to Bob Parish, the ACB chairman, and Ray Steele, the treasurer, in July 1976: `C'mon gentlemen. We're all whores. What's your price?' When the authorities proved strangely immune to his charms, he was receptive to the proposition of John Cornell and Austin Robertson for an independent international professional cricket attraction. Cornell and Robertson brought the players - sixty of them by the time recruiting was done - to which Packer added money, marketing and television.

It is worth pointing out that Packer didn't make cricket popular. He coveted it because it was popular, and perceived it as underpriced because you could buy the services of the players cheaply relative to their market value. What he improved was cricket's ability to exploit its popularity commercially. This he did in a variety of fashions, jazzing up television coverage, promoting the players as personalities, pitching the game as a product to the public that could be consumed over five days or one, by day or night, in white and coloured clothing. When that did not work at once, he twinged the popular patriotic nerve with a slogan centred on a pop song, `C'Mon Aussie C'Mon'. Initially reluctant, the public turned to support World Series Cricket in overwhelming numbers, the turning point being a game between the WSC Australians and the WSC World at the SCG in November 1978 attended by in excess of 50,000. Within six months, the ACB had sued for peace, not only granting Nine the exclusive broadcasting rights for Australian cricket but handing over marketing responsibilities to Packer's PBL Marketing.

The Packer Risorgimento in cricket became a model for the reinvention of a sport: Gary Kasparov once said that what chess needed was its own Kerry Packer. By the same token, it was hardly an act of selflessness, for Nine obtained hours of popular and profitable summer programming at hugely advantageous terms. `The deal with PBL was hardly a goldmine for cricket,' revealed Graham Halbish, former ACB CEO, in his autobiography Run Out (2003). `The Board still had all its obligations to look after the game but it had to share considerable revenue with PBL Marketing...When the agreement with PBL ended in 1989, after what many believed to be a fruitful and lucrative decade, the ACB's net assets had increased to $2.5 million. That hardly was megabucks.' So while on the whole it has been decided that Australian cricket did well out of Packer, it's arguable he did far better out of Australian cricket.

|

|

|

Packer would forever be identified with cricket, partly because sport is the measure of so much in Australia, partly because he was never again so public: he privatized the Consolidated Press empire in 1983, buying out minorities for a song at the end of a recession. Yet while he enjoyed cricket, he loved television most of all, boasting of watching it for four hours a day. In The Rise and Rise of Kerry Packer (1993), his biographer Paul Barry painted a vivid, somewhat melancholy portrait of Citizen Packer in his Bellevue Hill Xanadu: `He never read because he was dyslexic, rarely went out because he didn't drink, and had time on his hands because he was a lonely man with few friends.

Instead of books his library at home had videotapes. So each evening he would sit at home and watch television.' That made his eventual decision to part with the Nine Network in April 1987 all the more startling. This extraordinary deal, and one that showed just how much his father's son Kerry was. Offered an unrefusable price by Rupert Murdoch in 1972, Sir Frank had set aside sentiment and sold his best-loved media property, Sydney's Daily Telegraph. Fifteen years later, Kerry knew that the $1050 million offered by Alan Bond, an Australian entrepreneur, was vastly in excess of the network's value, and sold with a parting mot: `You only get one Alan Bond in your life and I've had mine.' In fact, Bond's management proved so ruinous that Packer was able to buy the network back for a fraction of its value within three years.

Packer was also his father's son in his attitude to life. His father, wracked by ill-health, lived every moment as though it was his last; Packer brazened out his many intimations of mortality. In October 1990, he actually died, being without pulse or respiration for six minutes after a heart attack following a game of polo. He came back defiantly. `The good news is there's no Devil,' he said. `The bad news is there's no heaven.' He developed into the highest of rollers, and his gambling exploits became legend; he won and lost corporate fortunes in positions he took in the foreign exchange market; he set a punishing regime of travel for business and pleasure.

Packer got another lease on life in 2001 when his pilot donated him a kidney, and his battles with illness leant his features an eerie plasticity. His face, which had once had a craggy grandeur, began to look like one of Dr Moreau's less successful experiments. Yet even then he hardly slowed down. He lived just a few months longer than did his father, dying at his home in Sydney's Bellevue Hill ten days after his 68th birthday, and shortly after flying back from Argentina to take over high-stakes negotiations by the Nine Network for Australian rules football broadcast rights.

Packer was such an object of such fascination in his lifetime that even his death seems like another event to be analysed; it's tempting simply to echo Metternich's famous remark on the death of Talleyrand: `I wonder what he meant by that.' Now the mantle of running the house of Packer falls on his son James, it is also tempting to prophesy decline. Yet one shouldn't be overhasty. In 1977, after all, you'd have obtained good odds on Packer's death eventually being marked by a minute's silence at the MCG, as there was on the morning of 27 December - the sort of odds that might even have appealed to the man himself.

Gideon Haigh is a cricket historian and writer