Henry delights in Ntini's achievement

Omar Henry has seen it all in South African cricket as a player, coach, administrator and commentator. But there was one moment he thought he'd never witness

Andrew McGlashan in Durban

22-Dec-2009

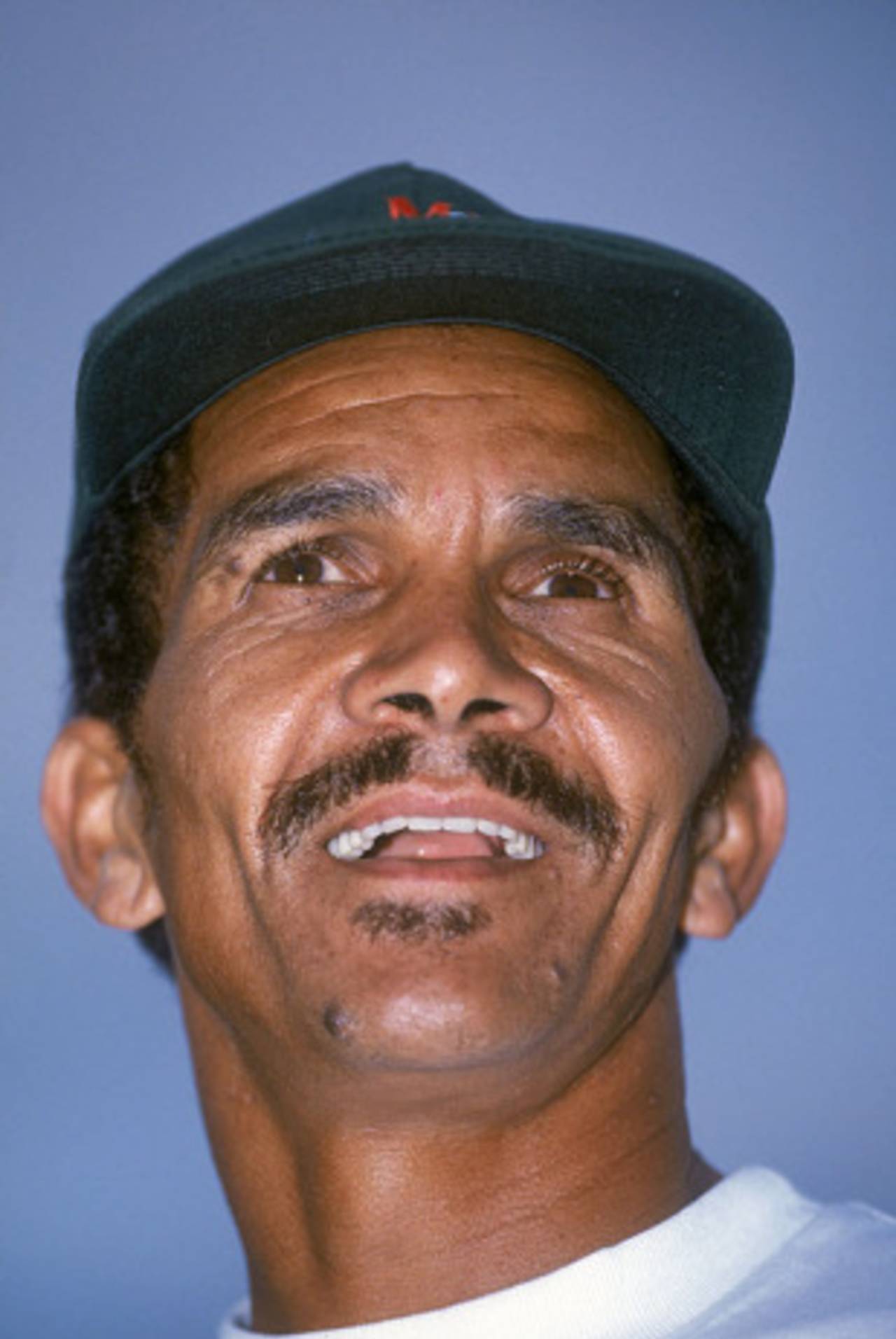

Omar Henry was the first non-white cricketer to play for South Africa • Getty Images

Omar Henry has seen it all in South African cricket as a player, coach, administrator and commentator. But there was one moment he thought he'd never witness, and it was with immense pride that he watched Makhaya Ntini play his 100th Test at Centurion Park.

"I didn't believe it would come in my time," Henry, the first non-white to represent South Africa, told Cricinfo. "I was hoping I would see an integrated South African side so in that respect, for me to have played and then to see Makhaya reach 100 matches has been a fantastic experience."

Henry, now 57, was one of the many South African cricketers denied a full international career by Apartheid. He managed three Tests and three ODIs between 1992 and 1993, but he was past his best as a left-arm spinner. Yet the fact that he managed a successful first-class career - 443 wickets at 25.17 - is where Henry stands out.

He crossed the barrier between black and white cricket by representing Western Province, Boland and Orange Free State as well as facing the rebel tourists of the 1980s. It earned him threats and Apartheid's laws stated he wasn't allowed to stay in the same hotels as his team-mates, or eat in the same restaurants. But Henry just wanted a chance.

"I was fairly realistic in the sense that when I started to play cricket knowing the situation we were, in my only ambition was to play cricket for a career," he said.

The thought of playing for his country never crossed his mind, so even though he never had a proper opportunity on the world stage, just getting that South African cap in his hand was more than enough reward.

"At the time I was in my 20s and it was almost impossible to think I would ever play," he said. "So when the time came there was no regret, it was more an achievement of the impossible. The fact that I was privileged and fortunate to be the first one was greater than anything else. And the fact the future generation would have a better life was even more encouraging."

However, it has been far from an easy path for South Africa. After Henry's brief top-level career, integration took a long time. The quota system was introduced and while Henry was never a true believer in the process, even during his time as convenor of selectors, he can see why it was necessary.

"Personally I was very much against quotas but in the same way I can understand why others insisted upon them," he said. "I feel that to a certain extent it was the right thing to do, but having said that we could have implemented it better and maybe differently.

"We've certainly made progress - Makhaya Ntini is a perfect example - but as with anything, for an action there is a reaction and there could have been a few more Ntinis if things had been handled differently. That is where I come from. If they had been implemented differently they could have been even more successful."

To point at the failings of the quota system, Henry refers back to the Justin Ontong affair. In 2002, Henry was Ontong's coach at Boland when the 22-year-old was shoe-horned into South Africa's team to face Australia, at Sydney, in place of his room-mate Jacques Rudolph. The move came at the behest of Percy Sonn, the South African board president, so that the team fulfilled the quota requirements.

"That was a lesson to be learnt and that brings me back to the point that if things had been done differently then certain incidents may not have happened," Henry said. "But when you start something there are going to be problems. Justin Ontong will probably be a victim of the system, and that's unfortunate.

"It probably left scars on them both [Ontong and Rudolph] and today both those talents are not on the park any more. So there are lessons to be learnt and in a changing environment you are going to get these types of cases. The positive is that we have made progress, we have maintained a high standard and been competitive for the last 17 years. The national team has really achieved a lot in a short space of time, but having said that, I firmly believe there is an enormous amount to be done and it will take a while."

Henry believes one of the key challenges now facing cricket in South Africa is to make it a truly national sport. There are heartlands around the country which have been the traditional bedrocks for talent - the Eastern and Western Capes, KwaZulu-Natal, Kimberley and Gauteng - but Henry knows there are vast swathes still untapped.

"Cricket in a lot of areas is well over 100 years old and we should really focus on that to strengthen our base," he explained. "Most importantly then is to broaden the support. There are pockets in the country where cricket is non-existent and we have to go in there and that's a long-term role. It will take patience and we can make cricket a truly national sport. You need a commitment to achieve that. It's a big country."

Some feel that South Africa hasn't moved quick enough over the last decade and a half, but Henry thinks expectations were unreasonably high when the divides came down. "Everyone wanted it so badly and so quickly," he said, and added that, in his view, the country is only now starting to find its identity.

"Sometimes it has been bumpy, sometimes aggressive, sometimes wobbly, sometimes tense, but that is part of growing up and maturing. Look at the ICC now with Haroon Lorgat the chief executive, Dave Richardson, Vince van der Bijl in key jobs. It tells you what this country can offer and I firmly believe we have only touched the surface."

Andrew McGlashan is assistant editor of Cricinfo