A brave but incomplete story

Lisa Sthalekar tackles the difficult topic of depression with maturity and candour in her autobiography, but fails to use the same rigour when discussing the rest of her career

Tariq Engineer

01-Apr-2012

Getty Images

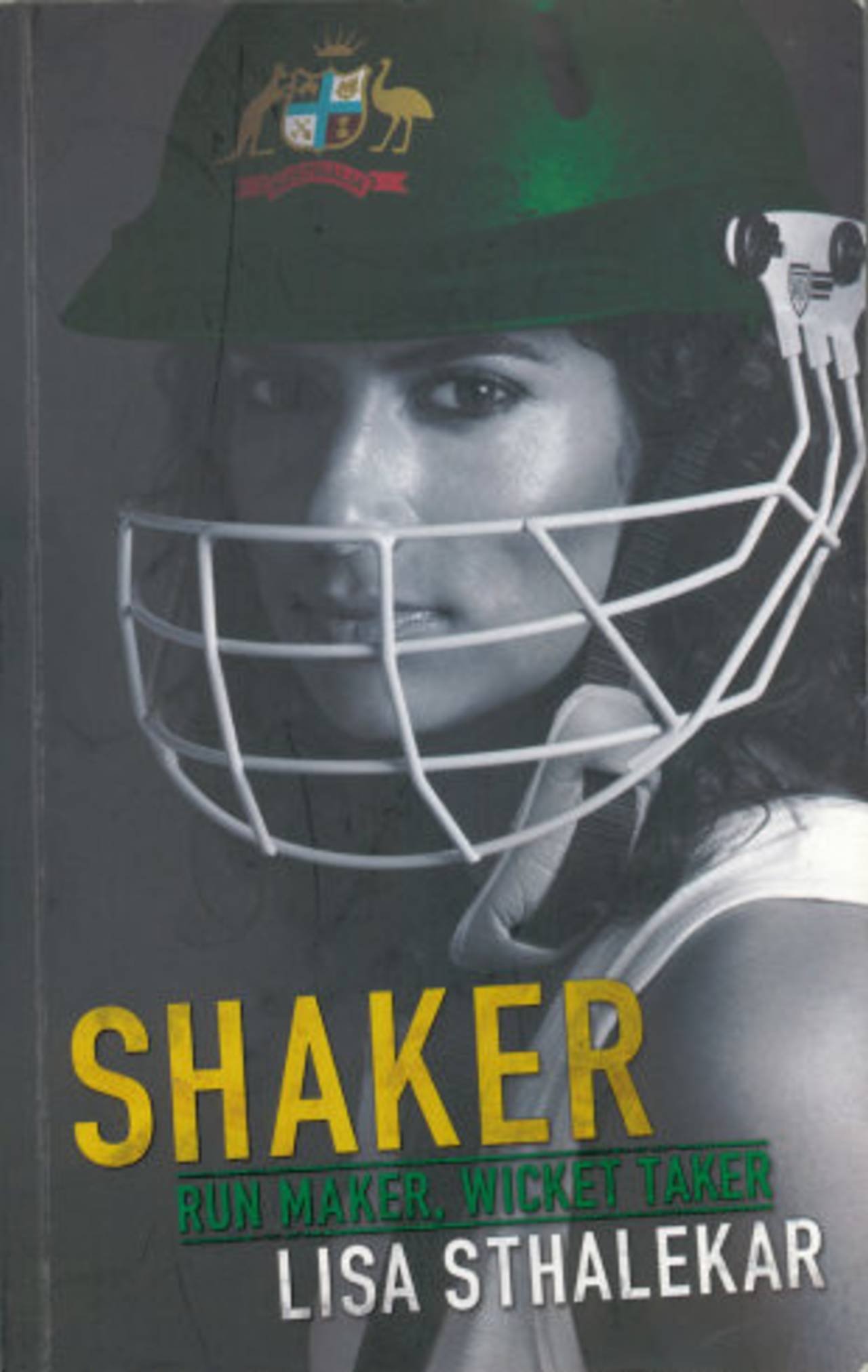

Marcus Trescothick, Iain O'Brien and Andrew Flintoff among others have in recent years publicly acknowledged their battles with depression and brought a difficult subject to light. Now Lisa Sthalekar, currently the No. 1 women's player in ODIs, takes the same brave step in her recently released biography: Shaker: Run Maker, Wicket Taker.

Women's cricket may only get a fraction of the public attention devoted to the men's version, but the pressures of the game are no less for it. Sthalekar, an orphaned Indian girl who was adopted by a bi-racial couple (Indian father, Australian mother) when she was three weeks old, began playing competitive cricket early. She admits she was not much of a student, so it is no surprise that her self-esteem is linked to her performances on the field. As Ed Cowan wrote in a column for ESPNcricinfo last July: "A professional sportsperson is his or her performances. From experience I can say it can feel like you have ceased to exist when failure is the story of your day."

In Sthalekar's case it was a combination of poor results for Australia and questions about her leadership ability that started to wear her down. When the same problems trickled down to state level, she lost her last refuge in the game. There appears to have been little sympathy or understanding from those administering the game and caring for the players. "I knew from then on there was no point telling anyone in the administration how I really felt, it only made things worse," Sthalekar writes in one of the more poignant lines in the book.

It took her father's urging to get her to realise she was dealing with depression and to seek help. She rejected the option of completely taking a break from cricket and played the World Cup on home soil; she decided instead "to go on some medication and try to segregate my world into work, playing cricket and home time". The family stopped discussing the game at home and slowly the fog lifted and she was able to go back to functioning "at a fairly normal level".

Sthalekar's stated intention in relating her story is that other players ought not to suffer the way she did. Hopefully those in positions of power are listening.

Dealing with depression is but one chapter in the book, the vast majority of which covers Sthalekar's playing career through to 2011. Sthalekar, though, appears reluctant to place her experiences in the wider context of women in sports, or even in the context of how the profile of women's cricket has changed since she started playing international cricket. (On top of playing cricket, she still needs to hold down a full-time job to pay the bills.)

The only discussion on women's cricket comes in the final chapter. That she still raises pertinent questions, such as those on the effect of Twenty20 cricket on a player's development, is perhaps proof that she should have run the same eye over her whole career in the book.

There is little also about how cricket and her experiences playing it have shaped Sthalekar's personality. She mentions, for instance, growing up without best friends or a stable social life because she was always travelling to play cricket, but it comes across as a mere fact, mentioned in passing.

We know Sthalekar is capable of insight and reflection from the descriptions of her depression and the chapter dealing with her mother's ultimately losing battle with breast cancer. In the latter there is an unexpected revelation towards the end of her mother's struggle that speaks of an emotional honesty and the ability to put those emotions in context. In contrast, Sthalekar's descriptions of games and tours are just that, descriptions, which ultimately lack depth.

Her story is also weighed down by poor organisation. The chapters are arranged by subject and not chronologically, giving the book a clunky, disjointed feel. A better editor and a wider lens would have lifted Shaker from an interesting look at the life and career of a woman cricketer to a captivating must-read about women's cricket and the life of a professional sportsperson.

Shaker: Run Maker, Wicket Taker

Lisa Sthalekar

The Global Cricket School and Shaun Martin Associates, 2012

Lisa Sthalekar

The Global Cricket School and Shaun Martin Associates, 2012

Tariq Engineer is a senior sub-editor at ESPNcricinfo