The soggiest of squibs

At the end of a wet summer, we look back to an even wetter one, and the death of a visionary idea

Martin Williamson

08-Sep-2012

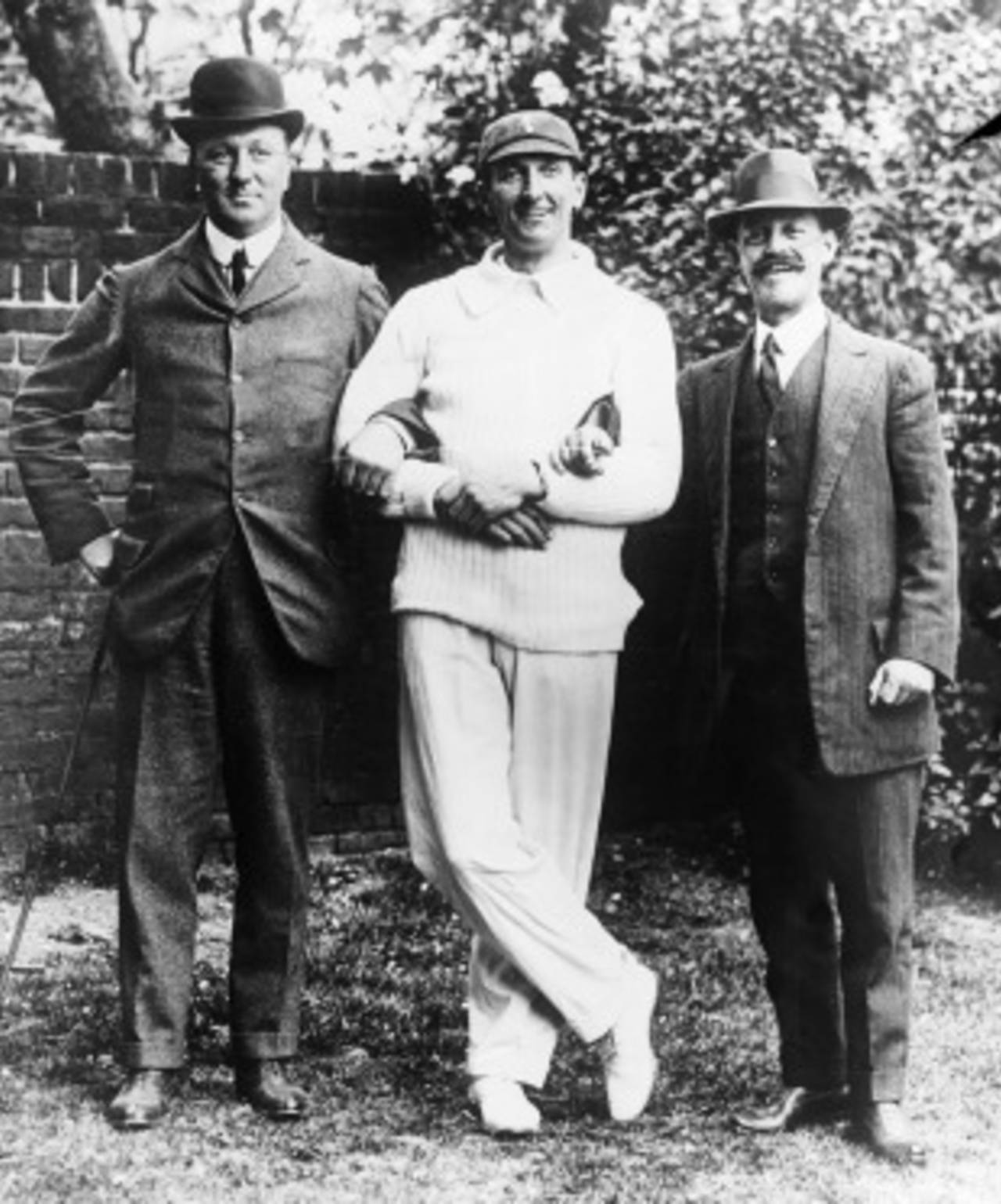

The three captains, Frank Mitchell (South Africa, left), CB Fry (England, middle) and Syd Gregory (Australia, right), pose ahead of the ill-fated 1912 Triangular Tournament. There were few smiles by the end • The Cricketer International

Although the English summer is drawing to a close in a blaze of sunshine the record books will show it was the wettest for a hundred years. That so much cricket was played despite the rain is testament to the vastly improved covering and drainage systems used on modern grounds. But a century ago covers were rudimentary, and even then limited to the most prestigious venues, and drainage was entirely at the mercy of slopes and soil.

Unsurprisingly, the 1912 season was ruined by the weather and there was not even the solace of a sunny finale. A soggy spring was followed by one of the wettest summers since records began to be kept in 1766. In June, July and August, rainfall was more than double the annual average, and to add to the misery, August also went into the record books as the coldest, dullest and wettest month of the 20th century. It was against that backdrop that one of the game's first imaginative ventures was tried and rejected.

The triangular tournament of 1912 was years ahead of its time. The idea was sound - a competition involving the only three Test-playing countries of the time, meeting each other three times - and was first mooted by South Africa's Sir Abe Bailey in 1907. "Inter-rivalry within the Empire cannot fail to draw together in closer friendly interest all those many thousands of our kinsmen who regard cricket as our national sport," he said. "Secondly it would probably give a direct stimulus to amateurism." That it failed was due to circumstances almost entirely beyond the control of the organisers.

The scheme was hatched at the inaugural meeting of the Imperial Cricket Council, the new world governing body, at Lord's in July 1909. At that gathering, such topics as eligibility of players to represent countries other than that of their birth, and a programme for Test series, were discussed - plus ça change. High on the agenda, and quickly agreed to, was a triangular contest, to be held in England in 1912 and thereafter every four years. The reservations of the counties, that this would result in too much cricket, were quelled by a deal whereby they would all be guaranteed lucrative tour matches against both visiting sides.

In 1909 the plan was most attractive. England and Australia were evenly matched, and South Africa were growing in strength and had won their most recent home series against England (in 1905-06) 4-1 - they were to win the 1909-10 series 3-2 - and had performed well in England in 1907, thanks to their phalanx of legspinners. But three years later it was a different story.

In the February of 1912 a simmering dispute between several leading Australian players and the recently formed Australian Cricket Board spilled over into open warfare. At a meeting of the selectors in Sydney, Clem Hill, Australia's captain, came to blows with a colleague, Peter McAllister. Underlying the animosity was the question of who should have the right to appoint the tour manager for the 1912 trip. The players, nominal amateurs, for whom the trip was a real money-spinner, thought they should, while the board, realising that there was cash to be made, stated it should. The end result was that the board won through and six leading players - Hill, Warwick Armstrong, Victor Trumper, Tibby Cotter, Hanson Carter and Vernon Ransford - refused to tour. Their absence manifestly reduced the box office appeal of the Australians.

The South Africans had problems of their own. Their earlier success had come largely thanks to their battery of legspinners and googly bowlers, who on the matting wickets then used in the Cape were lethal. But batsmen were becoming more used to playing the relatively new googlies and on English turf wickets the spinners' effectiveness was even further reduced.

When the three-country series was announced, the Times warned it could "furnish a surfeit of healthy excitement, which would defeat the purpose of wholesome cricket among those who have its best interests at heart". It need not have worried. Healthy excitement was not a phrase used by many to describe the events of the summer.

If Australia's lack of depth on the field was a worry, the squad's off-field antics were even more remarkable. The post-tour report by George Crouch, the board-appointed manager, spoke of bad language, poor manners and heavy drinking. Even the usually conservative Wisden was taken to observe that "some of the players were not satisfied with Crouch as manager", while adding his claim that some of the team had behaved so badly that the side was "socially ostracised". It was hardly surprising that the Australians' income from the tour was 40% down on their previous trip in 1909.

Even England had problems, with CB Fry's idiosyncratic captaincy openly criticised in the media. But the weakness of the opposition, allied to the strength in depth of the side and familiarity with the conditions, meant the tournament was a fairly one-sided affair.

Australia started well, with a crushing innings victory over South Africa in the tournament opener at Old Trafford, notable for Victoria's legspinner Jimmy Matthews uniquely taking a hat-trick in each innings (on the same day). Played in chilly conditions, the game attracted few spectators. England then eased to an equally comprehensive innings win over the South Africans at Lord's.

A waterlogged Lord's during the England v Australia Test•Wisden Cricket Monthly

Then the weather really closed in. Only four hours' play was possible on the first two days of the first Test between England and Australia at Lord's, and as all the matches were played over three days, significant interruptions condemned them to inevitable draws. The second meeting of the two sides, at Old Trafford, was even worse hit, and although there was some play, Fry complained that the pitch was "pure mud".

England eased to a second win over South Africa in Manchester; and in front of desultory crowds at Lord's, Australia beat South Africa as well by ten wickets. One of the few who attended that match was King George V, the first time a reigning monarch had watched Test cricket.

The final round of matches was just as uncompetitive. At The Oval, England polished off South Africa before lunch on the second day, with SF Barnes grabbing 8 for 29 inside 90 minutes. In the only match at Trent Bridge, appalling weather enabled South Africa to avoid a tournament whitewash against the Aussies.

By then the press were openly hostile. The Daily Mirror called it the "Doesn't Matter Cricket Season" and looking ahead to the series decider concluded "who cares". That finale came at The Oval, where it was agreed that the match would be played to a finish - the organisers had overlooked the need for a tiebreaker in the event of two sides finishing with the same number of wins, and so a definite result had to be achieved. A meeting had been held days before the match to consider an additional fourth Test should it be needed - the tenth of the summer - but there was no enthusiasm for the idea.

The first day at The Oval was sunny, but a wet outfield meant that Fry was unwilling to start promptly and play didn't get underway until midway through the afternoon. The crowd vented their feelings by booing Fry all the way to the middle when he came out to bat. Less than 90 minutes' play was possible on both the second and third days, but on the third Australia lost eight wickets for 21 runs on a "pitch better suited to water polo". They never recovered, and England won the match, the tournament and the Ashes.

It was fairly apparent that the experiment had not been a success, with the weather and public antipathy the crucial factors. "Nine Tests provide a surfeit of cricket," observed the Daily Telegraph, "and contests between Australia and South Africa are not a great attraction to the British public."

The Australian board had already reached that conclusion, sending a telegram in which it said there was "no point in continuing the triangular tours… [as] neither Australia or South Africa could finance two visiting teams in one season". Wisden concluded that "the experiment is not likely to be repeated for many years to come - perhaps not in this generation".

Bailey refused to admit defeat, adding that dull cricket as well as the weather and the weakness of the sides had been to blame. In that regard he had a point with the attitude of Fry at The Oval highlighting the unimaginative approach of the teams. Bailey concluded the future of the triangular series had to be in England, "as in Australia and South Africa there are no populations…[but] it is a matter for the conference to talk about".

Although the idea was not officially shelved, it never resurfaced after the First World War. It was to be another 63 years before a multi-national tournament was held again, and that - the 1975 World Cup - was an altogether more successful affair, helped by one of the hottest summers of the century.

What happened next?

- Australia's Warren Bardsley and Charles Kellaway, who scored hundreds in the neutral Test against South Africa, were only added to the honours board in the away dressing room in 2010

- England did not host another neutral Test until 2010, when Australia met Pakistan at Lord's

Martin Williamson is executive editor of ESPNcricinfo and managing editor of ESPN Digital Media in Europe, the Middle East and Africa