The art, and science, of batting with the lower order

A look at ten one-wicket wins in Test cricket, and what it tells us about batting with the tail

Anantha Narayanan

Aug 9, 2025, 3:24 AM

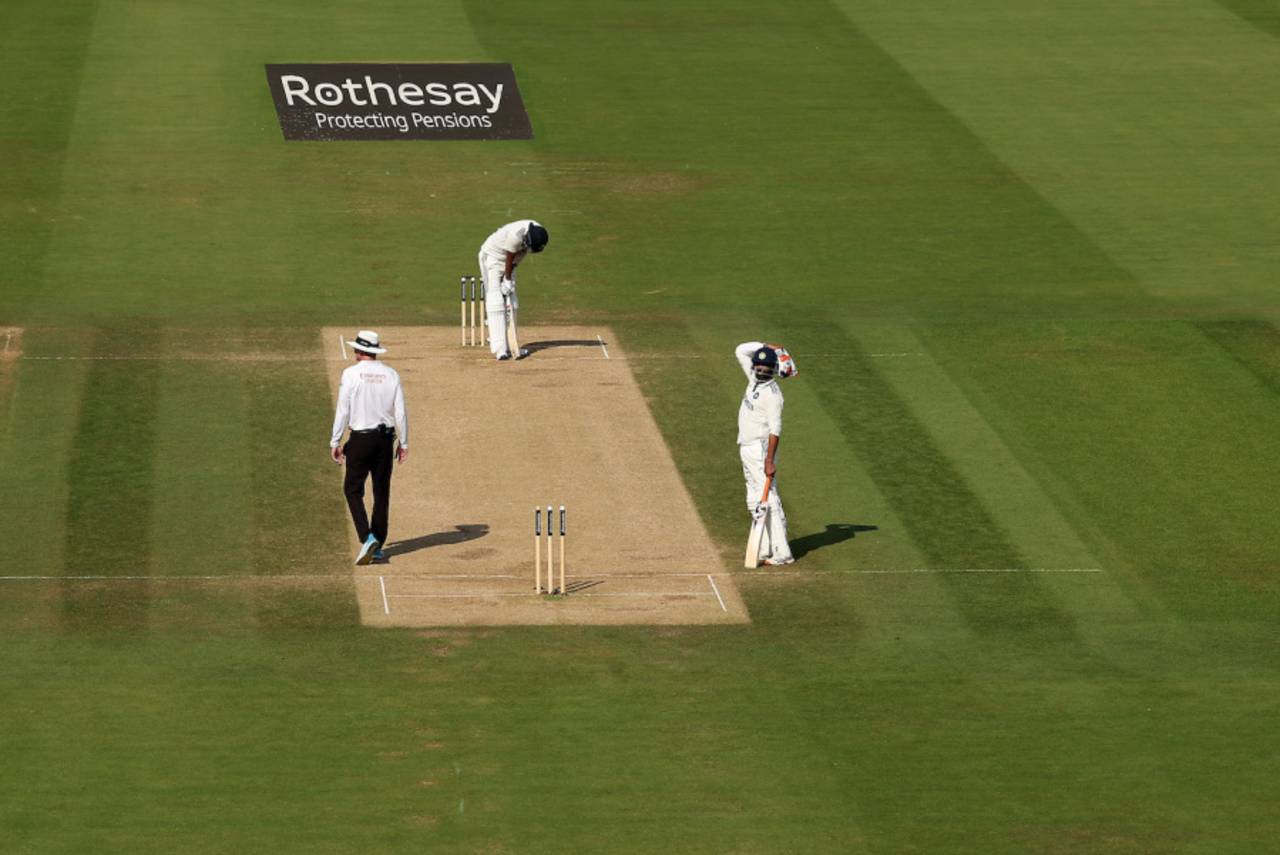

Ravindra Jadeja's strategy for the Lord's Test was to take on all the batting responsibility without depending on the tailenders, which eventually did not work in India's favour • Getty Images

The art of batting with late-order batters is to plan for the long haul. Understand the way the opposite captain and bowlers think and act. Decipher their body language. Understand one's own compatriots. Get a clear handle on their own strengths and weaknesses. Hand-hold them when necessary. Instil confidence in them. Transfer the pressure back to the bowling team.

A lot of what I have described is abstract, and is visible and possible only on the ground. As such, these are almost always in the batter's domain. Even the coaching and support staff may not be of any help.

The science of batting with the lower order is far more definable. What do we do in the next ball, over, 15 minutes? How do we optimise the next few overs? What is the objective for the next break? Which bowler do we go after? Who do we give respect to? Which fielder can we chance a run against? These are very clearly in the domain of the batter. For that matter, the junior partner can suggest this. And the coaching and support staff could offer their inputs. And nothing wrong with an outsider making a suggestion or two. That is what I intend to do.

There are many ways of batting with late-order batters. There is nothing implicitly right or wrong with any of these approaches. Saying that what worked successfully was a correct method is to over-simplify the whole thing. Context is very important. The approach adopted by the top-order batter has to be context-sensitive. And what worked at one stage of the innings might not necessarily work later in it. There is a need to shift strategies continually.

Let me first outline the possible methods.

1. Trust the late-order batters implicitly. The Australians have almost always taken this approach. A possible reason could also be that their late-order batters take batting seriously. No Australian who has played in 50 innings has a batting average below 6.5. While it may depend on the overall quality of the late order, the benefit is that the batters grow in confidence as they move forward. The responsibility vested in them manifests in a positive manner.

2. A variant of the first approach: use the close field placement pattern to attack and score runs. Then take singles and trust the late-order batter to defend well. This method necessarily requires that the top-order batter has to back his supporting batters implicitly.

3. Have virtually no trust in the late order. Through the innings, however long it turns out to be, bat for four to five balls and take a single to move to the other end. Keep doing this, hoping that things will work well at the end. This is the approach Ravindra Jadeja adopted at Lord's.

4. A variant of the third approach: start on the low-trust policy, but adapt as the innings moves on. As the late-order batter plays more and more responsibly, increase the trust in him and play differently. Possibly, the sanest and most effective of all approaches.

Inzamam-ul-Haq's rescue effort in Karachi in 1994 was buttressed by significant contributions from Rashid Latif and Mushtaq Ahmed•Getty Images

Even though this analysis stems mainly on one innings, that of Jadeja's at Lord's, it is a general one with his innings being used as a recent valid sample for analysis to derive conclusions and offer alternatives.

I will now move onwards to a few occurrences of top-order batters who played effectively with the lower order to achieve memorable come-from-behind wins. The first three innings are not considered since there are no win-or-loss situations there.

There are 15 one-wicket wins in the history of Test cricket. For the sake of simplicity I have only considered the ten wins in which there were effective late-order partnerships. I have ignored those wins in which wickets fell in a clump towards the end while the winning team scraped through. Or matches in which many batters contributed. I have also ignored the 20 two-wicket wins to keep the sample size manageable.

England vs Australia, The Oval, 1902 (263 for 9)

Gilbert Jessop's century was scored at breakneck pace. Then George Hirst and Wilfred Rhodes could afford to "do it in singles". The main late-order support batters were Hirst (58) and Dick Lilley (16). The key aspect in this match was that, even as far back as 1902, the scoring rate was around four runs per over. That means that despite losing their five wickets for a mere 48, England were attacking, with Jessop leading the way.

Gilbert Jessop's century was scored at breakneck pace. Then George Hirst and Wilfred Rhodes could afford to "do it in singles". The main late-order support batters were Hirst (58) and Dick Lilley (16). The key aspect in this match was that, even as far back as 1902, the scoring rate was around four runs per over. That means that despite losing their five wickets for a mere 48, England were attacking, with Jessop leading the way.

Pakistan vs Australia, Karachi, 1994 (315 for 9)

Inzamam-ul-Haq scored 58 at a strike rate of 65. The last three wickets added 131 runs at 4.2 runs per over. The main late-order support batters were Rashid Latif (35 off 56) and Mushtaq Ahmed (20 off 30). Note their powerful contributions. This was a rare match in which the main batter was matched in scores by the support batters. This was a really cooperative effort.

Inzamam-ul-Haq scored 58 at a strike rate of 65. The last three wickets added 131 runs at 4.2 runs per over. The main late-order support batters were Rashid Latif (35 off 56) and Mushtaq Ahmed (20 off 30). Note their powerful contributions. This was a rare match in which the main batter was matched in scores by the support batters. This was a really cooperative effort.

West Indies' one-wicket heist over Australia in 1999 was an example of the main batter's - Brian Lara's - growing trust in the lower order paying off•Getty Images

West Indies vs Australia, Bridgetown, 1999 (311 for 9)

Brian Lara scored 153 runs at a strike rate of 60. The last three wickets added 63 at 3.5 (strike rate 57). The main late-order support batter was Curtly Ambrose (12 off 39). There is no doubt Lara shepherded the late-order batters, but not to a level where it would have meant that they would be relieved of the pressure. As Ambrose batted on, Lara trusted him more, making sure that the tempo of the game was maintained.

Brian Lara scored 153 runs at a strike rate of 60. The last three wickets added 63 at 3.5 (strike rate 57). The main late-order support batter was Curtly Ambrose (12 off 39). There is no doubt Lara shepherded the late-order batters, but not to a level where it would have meant that they would be relieved of the pressure. As Ambrose batted on, Lara trusted him more, making sure that the tempo of the game was maintained.

Pakistan vs Bangladesh, Multan, 2003 (262 for 9)

Inzamam scored 138 runs at a strike rate of 59. The last three wickets added 98 runs at 3.1 (strike rate 51). The main late-order support batters were Saqlain Mushtaq (11 off 51), Shabbir Ahmed (13 off 25) and Umar Gul (5 off 50). It is clear that the late-order batters played defensively. However, Inzamam more than compensated for this slow scoring with his attacking batting.

Inzamam scored 138 runs at a strike rate of 59. The last three wickets added 98 runs at 3.1 (strike rate 51). The main late-order support batters were Saqlain Mushtaq (11 off 51), Shabbir Ahmed (13 off 25) and Umar Gul (5 off 50). It is clear that the late-order batters played defensively. However, Inzamam more than compensated for this slow scoring with his attacking batting.

India vs Australia, Mohali, 2010 (216 for 9)

VVS Laxman scored 73 runs at a strike rate of 92. The last two wickets added 92 runs at four runs per over (strike rate 67). The main late-order support batter was Ishant Sharma (31 off 92). This was a strange innings. Laxman took the Australian bowlers to the cleaners. He would hit a boundary, despite a defensive fielding set-up, coolly take a single, and let Ishant play his immaculate defensive game. A remarkable fact is that Ishant faced more balls than Laxman, who scored at nearly a run a ball. One of the great innings of all time. One reason why I rate this no less than the 281.

VVS Laxman scored 73 runs at a strike rate of 92. The last two wickets added 92 runs at four runs per over (strike rate 67). The main late-order support batter was Ishant Sharma (31 off 92). This was a strange innings. Laxman took the Australian bowlers to the cleaners. He would hit a boundary, despite a defensive fielding set-up, coolly take a single, and let Ishant play his immaculate defensive game. A remarkable fact is that Ishant faced more balls than Laxman, who scored at nearly a run a ball. One of the great innings of all time. One reason why I rate this no less than the 281.

South Africa vs Sri Lanka, Durban, 2019 (304 for 9)

Kusal Perera scored 153 runs at a strike rate of 76.5. The last three wickets added 98 runs at 4.4 (strike rate 73). The main late-order support batter was Vishwa Fernando (6 off 27). Perera played this like Laxman in Mohali, attacking the bowling often. His innings contained five sixes. This is proof that he never let the innings drift. And this, let us not forget, was against Dale Steyn, Vernon Philander and Kagiso Rabada.

Kusal Perera scored 153 runs at a strike rate of 76.5. The last three wickets added 98 runs at 4.4 (strike rate 73). The main late-order support batter was Vishwa Fernando (6 off 27). Perera played this like Laxman in Mohali, attacking the bowling often. His innings contained five sixes. This is proof that he never let the innings drift. And this, let us not forget, was against Dale Steyn, Vernon Philander and Kagiso Rabada.

England vs Australia, Headingley, 2019 (362 for 9)

Ben Stokes scored 135 runs at a strike rate of 62. The last three added 101 at a strike rate of 85. The main late-order support batters were Jofra Archer (15 off 33) and Jack Leach (1 off 17 - his contribution out of a last-wicket partnership of 76). Stokes was more careful than Laxman and Perera, but attacked when he could to keep the pressure on the Australian bowlers. Stokes' innings was similar to Perera's in that it contained eight sixes. The key fact is that all three batters - Laxman, Perera and Stokes - showed total intent.

Ben Stokes scored 135 runs at a strike rate of 62. The last three added 101 at a strike rate of 85. The main late-order support batters were Jofra Archer (15 off 33) and Jack Leach (1 off 17 - his contribution out of a last-wicket partnership of 76). Stokes was more careful than Laxman and Perera, but attacked when he could to keep the pressure on the Australian bowlers. Stokes' innings was similar to Perera's in that it contained eight sixes. The key fact is that all three batters - Laxman, Perera and Stokes - showed total intent.

Ben Stokes balanced attack and wariness in his epic innings in the 2019 Ashes•Getty Images

West Indies vs Pakistan, Kingston, 2021 (168 for 9)

Kemar Roach scored 30 runs at a strike rate of 58. The last three wickets added 54 runs at a strike rate of 50. The truth is that Roach himself was a late-order batter, but he batted like a top-order one. He controlled the strike only to the extent necessary and kept the scoreboard moving. He played sensibly, like a seasoned top-order batter.

Kemar Roach scored 30 runs at a strike rate of 58. The last three wickets added 54 runs at a strike rate of 50. The truth is that Roach himself was a late-order batter, but he batted like a top-order one. He controlled the strike only to the extent necessary and kept the scoreboard moving. He played sensibly, like a seasoned top-order batter.

The bottom line is that in almost all these situations, going totally defensive would not have worked. Sooner or later, the late-order batter would have lost his wicket. And perhaps, the main batter himself might have succumbed. The pressure had to be put back on the bowlers. And all these batters scored at a decent pace. Also, the late-order partnerships were not allowed to drift.

The following were the two Tests in which slow batting won the Test. The one common theme for these Tests is the quality of bowling attacks. So, it is very clear at this distance in time that this was the only way to win. There was no question of attacking these all-time-great bowlers. They would have had the batters, especially the late-order ones, for breakfast.

New Zealand vs West Indies, Dunedin, 1980 (104 for 9)

New Zealand scored 104 in 50 overs. The last three wickets added 50 runs at a strike rate of 33. The bowling attack was a ferocious one - Michael Holding, Colin Croft, and Joel Garner. An excess of short-pitched bowling featured in this innings. A little more of directed bowling could have won the Test for West Indies. This match featured Holding's infamous kick at the stumps.

New Zealand scored 104 in 50 overs. The last three wickets added 50 runs at a strike rate of 33. The bowling attack was a ferocious one - Michael Holding, Colin Croft, and Joel Garner. An excess of short-pitched bowling featured in this innings. A little more of directed bowling could have won the Test for West Indies. This match featured Holding's infamous kick at the stumps.

West Indies vs Pakistan, Antigua, 2000 (216 for 9)

Jimmy Adams scored 48 runs at a strike rate of 23. The last three wickets added 39 runs in 25 overs. The bowling attack was an all-time-great one - Wasim Akram, Waqar Younis, Mushtaq Ahmed, and Saqlain Mushtaq. And there was clear evidence of umpiring errors. Adams was quite lucky.

Jimmy Adams scored 48 runs at a strike rate of 23. The last three wickets added 39 runs in 25 overs. The bowling attack was an all-time-great one - Wasim Akram, Waqar Younis, Mushtaq Ahmed, and Saqlain Mushtaq. And there was clear evidence of umpiring errors. Adams was quite lucky.

The fact that eight out of ten Tests were won by teams adopting more proactive means is a clear indication that in such situations, teams should not go totally defensive, ceding the initiative to the bowling teams. In the other two matches, against those bowling attacks, the only option available for the batters was to defend and hope for the best. On another day, both could have been lost.

Jimmy Adams and West Indies' slow creep towards a one-wicket win against Pakistan in 2000 had an element of luck to it•AFP

Now let us come back to Lord's.

Jadeja scored 61 runs at a strike rate of 34. The last three wickets added 88 runs at 1.6 runs per over. Just the bland facts. But they do tell a story.

Let me clearly inform the readers that in no way am I blaming Jadeja. I have no qualifications to do so. As of date, he has played 85 more Tests, faced 7037 more Test balls, and scored 3886 more Test runs than I have. I can barely hold the bat. He is a world-class Test batter. I am only going to present an alternate strategy that he could have tried. And/or the Indian management/support staff could have suggested. Purely from a theoretical point of view, let me add.

And let me also say that more eminent players of repute and commentators have made suggestions on similar lines. For that matter, it could have been an English batter who played in this manner. In that case, his innings would have been featured here.

The problem was that in most of the overs, it was a single, and nothing more. The dot balls were mandated for balls 1-3 and 5-6, or 1-4 and 6. The No. 10 or 11 batter could not even take a single off these latter deliveries, even if available. That meant that the 80 runs needed would have required 50-55 overs. That is too long a time for a batter to shepherd Nos. 10 and 11. It would be worth trying if they were late-order batters with averages of 15-20. Not with Bumrah/Siraj.

What were the alternatives?

Wait for Jasprit Bumrah or Mohammed Siraj to last 20 balls. Be convinced that they are fine defending, and Bumrah, especially, does not think that he can repeat his feat of scoring 35 in 6 balls.

Then take a calculated risk and change the approach. Maybe after the mid-afternoon drinks break. Take the single off the first ball. That is guaranteed. This certainly gives a headache for the bowlers. Can they go on an all-out attack? Bumrah or Siraj's mishits might be fours. So they would have in-out fields. That means the tailender could go for a single off the second or third ball. Now the fourth ball comes. But you have two runs in the bag. Aim for three every over, not one.

I know what some might say: the game cannot be calculated so precisely and played this way. I am sorry, I disagree strongly. It can, and should be played this way. It has to be a very finely calculated gamble. The tactics had to be invoked in flight, so to say. If not by the batter on the field, then by the coaches. To those who say that the late-order batter could be dismissed off the second or third ball, I can only point out that they could also have been dismissed off the fifth or sixth ball. There are no guarantees anywhere.

Jadeja's passive fight on the fifth day of the Oval put no pressure on England's bowlers, and a fateful ball seemed just a matter of time•Getty Images

The problem was that Jadeja did not trust Bumrah and Siraj even after they had lasted 20 balls each, showing that they were batting sensibly. And the ball was doing nothing. A bit more trust in these two, and a changed strategy could have won the game, and Jadeja's innings would have gone on to the lists of the truly great innings.

The lesson for such situations is simple. Do not have a fixed idea for hours on end. Somewhere there, sooner or later, one ball will misbehave and the batter, whether skilled or not too skilled, will get a ball with his name on it. At Lord's, it was later. Normally, it is sooner. Top-order batters can play for a full day to win or save a Test. Not the late-order batters. So, it is necessary for top-order batters to adopt different strategies and not be bound by a single strategy for hours on end. They have to think proactively. Move the pressure back to the bowling team.

I admire Jadeja's outstanding effort at Lord's. However, it was clear that the strategy was so fixed and so passive that there were continuous talks of the new ball. That was more than 30 overs away. At no time was the England bowling put under pressure. It was telling that the seven overs by the two spinners went for seven runs. The game meandered on until the two "named" balls came. For those who think I am faulting Jadeja, you should understand that simply calling a spade a spade is not wrong.

Finally, a word or two of appreciation for Stokes' magnificent bowling effort. He gave nothing away and, in between, bowled deliveries that produced wickets. Rarely has a captain put everything on the line as he did. The win was well-deserved and hard-earned. It looks like he is the one who needs some rest, not Bumrah.

In the first three innings, there are no real targets. A score to be set, a lead to be obtained, and a final target to be set form notional targets for the three innings. There is nothing wrong with any method tried when batting with late-order batters in those innings.

A brief note on The Oval Test

At The Oval last week, there were three important last-wicket partnerships. Whatever Washington Sundar tried (a more aggressive approach) or what Harry Brook attempted (a more conservative approach) were both correct and cannot be faulted. We could crystal-gaze whether Brook could have been more attacking, that being his natural game. However, it is also clear that the more attacking method of Washington ultimately proved to be the match-winning one.

Washington Sundar and Harry Brook took contrasting approaches to late-order batting in the Oval Test, with the former's winning out•Getty Images

It is impossible to analyse the last partnership between Gus Atkinson and Chris Woakes because of the presence of the huge X-factor, which was Woakes' injury. If he had to face even a single ball, what would he have done? So, we have to accept that Atkinson worked on the basis that he could not let Woakes face a single ball.

Another what-if: Woakes faces a ball, the Indian bowlers misguidedly try a short ball, and Woakes is hit on the helmet. And there is a concussion substitute on the horizon. Brydon Carse walks in.

What I have suggested is only for the last innings where there is a clear target, drawing a line in the sand defining a win or defeat. This is not a blueprint for batting with late-order batters in the fourth innings. It is a take on possible alternatives that could be considered. A totally theoretical alternative, may I add. But one that could work.

A note on the ODI bowlers analysis

In 2020, I had done a best ODI batter analysis and did a follow-up on that a couple of months back. The update was meaningful since I was able to come to a conclusion that Virat Kohli could very well overtake Sachin Tendulkar in the next two years for the top place since this is the only format Kohli plays. Also, that Rohit Sharma could leapfrog Viv Richards. These were significant potential moves.

I was going to do a similar update on ODI bowlers this month. When I completed the work, I realised that there were very few changes in the table compared to the 2020 list. The top four remained the same. The next six bowlers are the same in slightly different order. However, the most important fact is that the two current bowlers who have any chance of challenging the top five, Mitchell Starc and Rashid Khan, are not making any moves up. They are, in fact, slipping down the list.

Since I have no clear insight to add in the bowler analysis, regretfully, I have decided not to do the ODI bowlers article. In any case, the key insights of the current analysis have been presented above.

Potpourri

This time I have looked at Tests in which the four innings were very close to each other.

The last column shows the sum of the absolute variances from the mean. Since each Test has four innings, the SumVar value is a clear pointer to the closeness of the scores. The 1974 Test between Australia and England in Melbourne was amazing in that the four scores were within six runs of each other - the closest in history. It was also a terrific draw. Eight years later, one of the most famous wins of all time occured at the same venue. England won by three runs in a match in which the four scores were within ten runs of each other. At The Oval in 1890, a low-scoring Test between England and Australia had four scores either side of 100, within a ten-run range. England won by two wickets.

Talking Cricket Group

Any reader who wishes to join my general-purpose cricket-ideas-exchange group of this name can email me a request for inclusion, providing their name, place of residence, and what they do.

Any reader who wishes to join my general-purpose cricket-ideas-exchange group of this name can email me a request for inclusion, providing their name, place of residence, and what they do.

Email me your comments and I will respond. This email id is to be used only for sending in comments. Please note that readers whose emails are derogatory to the author or any player will be permanently blocked from sending in any feedback in future.

Anantha Narayanan has written for ESPNcricinfo and CastrolCricket and worked with a number of companies on their cricket performance ratings-related systems