The Jack of all rabbits

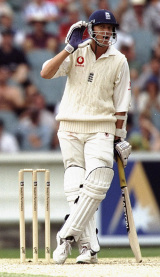

Tail-end Charlies are not what they were. The old England No.11 is an endangered species. Simon Lister marks the passing of an institution with a knock-out for eight of the worst. And the worst of the lot is...

Simon Lister

23-Jul-2007

Tail-end Charlies are not what they were. The old England No.11 is an endangered species. Simon Lister marks the passing of an institution with a knock-out for eight of the worst. And the worst of the lot is...

|

|

|

The 1985 Wisden Almanack carries a photograph of Pat Pocock terribly squared up by a Malcolm Marshall bouncer. He is flinching one way, one foot off the ground; his bat points the other way. It is the pose of an out-and-out tailender. Pocock batted four times against West Indies that summer; four times he made nought.

All the world knew that Pocock and cricketers like him were not batsmen, simply bowlers who now and again had to walk to the crease serenaded by the rumble of the heavy-roller.

For a decade after Pocock, England often had an awful batsman at No. 11. Some, like Devon Malcolm or Philip Tufnell, were almost as well known for their smears and dead-cert ducks as they were for their bowling. Remember the Test match against New Zealand in

1999 when England played not one but four No. 11s? Reeling off that lowest of lower orders - Andy Caddick, Alan Mullally, Tufnell, Ed Giddins - is like recalling a list of infamous British military disasters.

That was about as bad as it got, because when Duncan Fletcher arrived, the No. 11 became less of an object of derision. They learned the forward press and knew it had nothing to do with ironing their whites. The diehard No. 11 died out elsewhere too. The once hopeless

Australian tailender Jason Gillespie did something that Mike Atherton never did; he scored a Test double-hundred.

Yet when Monty Panesar was first picked for the tour of India in 2005-06 it seemed a fine English tradition had been revived. He was, said one cricket reporter, "a tail-end rabbit in the Watership Down class". Fletcher admitted: "I have slight reservations about his

batting." But that has changed. Panesar is a shoo-in for England, even for the one-day side. Rumours of his uselessness with the bat were exaggerated. So, if he still nearly failed to make the side because of his batting, what chance a Phil Tufnell playing for England today?

The era of the really awful No. 11 seems over and TWC decided it was a good time to look back at the 1980s and '90s - a golden age of English tail-end incompetence. Among those who could boast that the size of their boots was twice their batting average, who was worst of all?

Quarter-finals

Mullally v Pocock

Mullally, I fear, is too strong for Pocock in the first quarter-final. After all Pat had not played a Test for eight years when he volunteered for target practice against the 1984 West Indians. Bravery is not a quality we want, so Mullally is through.Giddins v Cowans

Giddins was a truly awful No. 11. Seven times he batted for England and he finished with a career average of 2.50. On three of those occasions he made a duck. Cowans, on the other hand, had 29 Test innings and got only five blobs. His average is like a skyscraper next to Giddins' bungalow - a mighty 7.95. Ed, you're through. Norman, thanks for coming and have a safe journey home.|

|

|

Tufnell v Such

No upsets here. Peter the Tweaker finished his career with an England average of 6.09. Tufnell's was a mere 5.10 from 59 innings. His excuse now? "When I batted, I was permanently confronting lost causes." Not this time, Phil, you've booked yourself a place in the semi-finals.Malcolm v Fraser

Two real triers go head to head in the last quarter-final. Angus Fraser does himself no favours because he genuinely wanted to get better. And he had bottle. The former England coach David Lloyd remembers Old Trafford 1998 against South Africa. England, following on, could not win but a draw would keep them in the series. "Right," said Fraser, as he went out to face Allan Donald. "The only way he'll get me out is if he knocks me through all three.""I said: 'He probably will, Gus, but good luck,'" chuckles Lloyd. "But he survived. A red-inker it was and in retrospect one of the most important innings of the series".

Devon Malcolm has different memories of batting for England. Sixteen scores of nought make him a very strong candidate for the next round. And this recollection clinches it. "We were in South Africa and I had been watching Atherton in the nets and something clicked. I thought, 'I want to try these shots.' The batting coach on that tour was John Edrich. He came over to see who was playing so sweetly, took one look at me and walked away." And

that was that. Devon never did open for England, but he does make the next round.

Semi-finals

Giddins v Mullally

An interesting one. Had Giddins played many more than four Tests, it is hard to believe that his tiny total of seven runs would have risen much higher.Mullally's modesty in the runs department, however, is forged with an iron consistency. From November 1998 until August 2001 it went like this: 0, 0, 0, 0, 4, 0, 16, 0, 0, 10, 5, 3, 10, 0, 0. "Thank you, Mr Mullally. Do you have the issue number and the expiry date?" Giddins can't compete with that. Alan, get your suit measured up. You're off to the final.

Malcolm v Tufnell

But whom will Mullally take on? Malcolm v Tufnell is tasty - 58 innings versus 59; 16 ducks versus 15. Malcolm's average is 6.05, Tufnell's, as mentioned, a shade over five. Yet here is the clincher. Devon gamely made 236 runs in big cricket, Tufnell just 153. And what about attitude? That incident in the nets proves that Devon wanted to get better. Did Phil?"I was a little bit lazy and often wasn't motivated when I batted," he admits now. "It was difficult to see how a regular net would ever get me a Test match hundred." Spoken like a true No. 11, Phil. March on, my boy.

THE FINAL: Tufnell v Mullally

|

|

|

And so to the final. Alan. Philip. No biting, no gouging, please, gentlemen. No Chinese cuts. The winner will be the first man who wafts at a full straight one while backing away.

Both men are here on merit. Test averages of around five prove that, and on paper the first instinct is to say that Tufnell should take the trophy. The boy who opened the batting at school certainly talks a good game. Was he frightened of fast bowling?

"It wasn't fear, it was apprehension. They were all brilliant, the bowlers I faced. If I can't see Allan Donald in the middle, what's the point of practising in the nets? I'm confident that, given a half-volley outside off stump, I would have put it through cover for four but all I remember ever getting were bouncers. They were all at my bloody head."

But Phil is hiding something. While he was famed for taking guard as near as he could to square leg, he was bowled only four times in his whole Test career. When no one was looking, he was getting into line. He also had 29 not outs, which suggests some level of application. In fact he admits it: "I've seen many a man through to his hundred. I knew how to knuckle down."

Mullally, on the other hand, walked undefeated to the pavilion only four times. Cheap as chips his wicket was - and as widely available. His 23 Test dismissals were to 15 different bowlers. On one occasion he even offered himself to Sourav Ganguly.

The temptation is to declare this contest a dead heat, except for one thing: hubris. Tufnell knew he was rubbish. Mullally apparently did not.

It is The Oval, 1996; the third Test against Pakistan; the England coach David Lloyd again. "I made Alan a bet. I said: 'You get 30 and I'll buy you 30 pints of Guinness. That's a promise.' Now, he wasn't a big drinker but he took it on."

Remarkably, against Wasim and Waqar, Mullally started to score - quickly, too. Within a quarter of an hour he had hit five boundaries and made 24. "It was then that he gestured to the dressing room," remembers Lloyd. "He made a drinking-a-pint sign with his hand. I even heard him shout to me, 'Get 'em in!'"

That was enough for Wasim Akram, who promptly knocked out Mullally's poles, with the hero six short of an unlikely prize. He got so close.

Did Lloyd pay out anyway? "No. Of course not."

Mullally is the complete package, the jack of all teams: a tiny average, lots of ducks, hardly any not-outs, and the foolhardy belief that he could carve the world's best bowlers to all quarters. Al, you may have missed out on four gallons of stout but you have won a far, far greater prize.