What does the scoring spree of the 2024 IPL tell us?

An analysis of the ramifications of the higher scoring rate and the impact sub on the contest between bat and ball

Kartikeya Date

07-Jun-2024

The average team total in the 2024 IPL was 191, the highest in the 16-year history of the tournament • BCCI

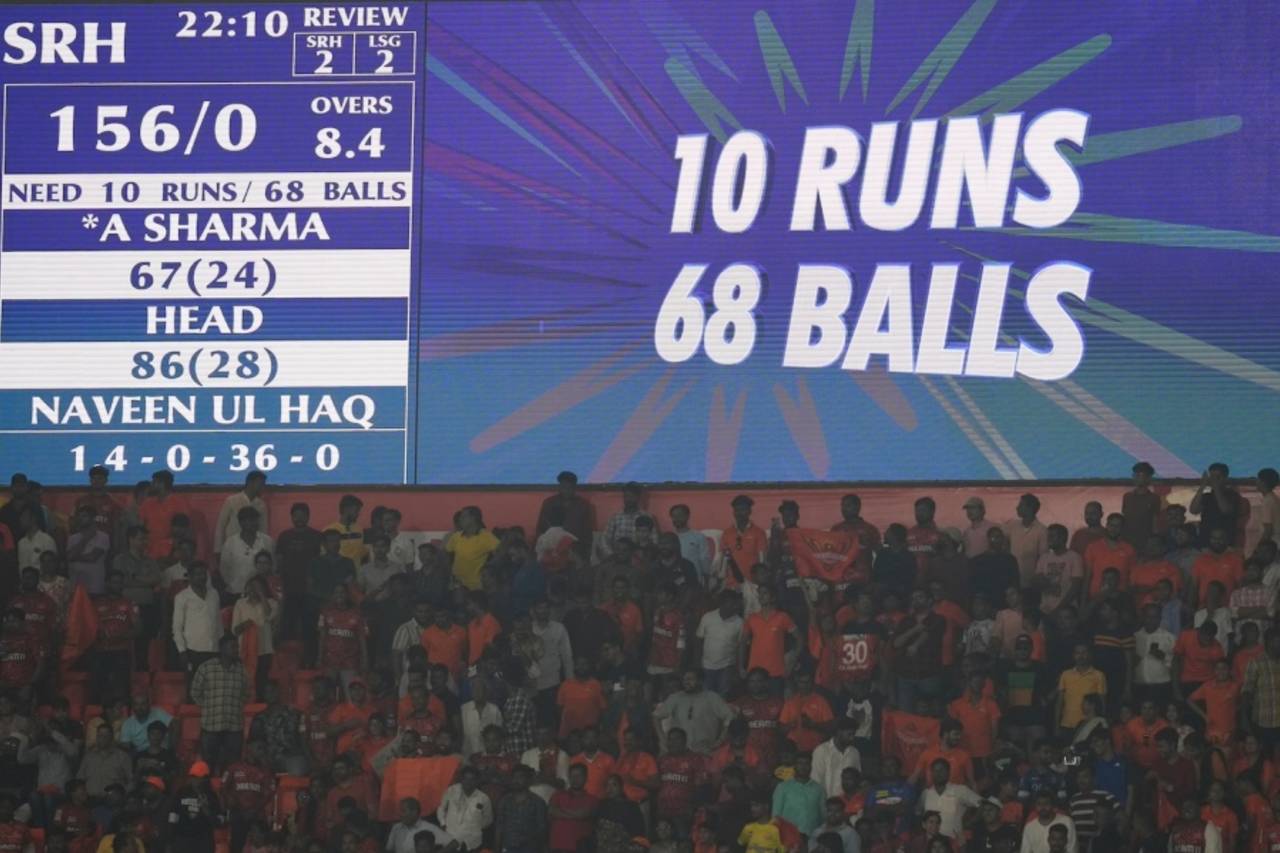

This year's IPL was like no previous edition. Records for the most runs in the powerplay, the largest team totals, and the biggest run chases were broken at least once during the tournament. The bowlers who conceded 8.7 an over in the 2023 tournament went at 9.4 an over in 2024.

This scoring spree raised three questions that are considered in this article using the control and shot-category record produced by ESPNcricinfo.

First, what are the implications for the contest between bat and ball if ten runs an over becomes a common scoring rate in an IPL match? Second, why is the scoring rate increasing? And third, what is the effect of the impact substitute rule?

The balance between bat and ball

The rate of scoring in the 2024 IPL caused some discomfort among experienced observers about where the contest between bat and ball was headed. These old-timers were making a category error: T20 was never cricket. It could not be, with batting sides having ten wickets to spend over only 120 balls.

The rate of scoring in the 2024 IPL caused some discomfort among experienced observers about where the contest between bat and ball was headed. These old-timers were making a category error: T20 was never cricket. It could not be, with batting sides having ten wickets to spend over only 120 balls.

Batters can do one of two things to a delivery in cricket. First, they can aim to hit it in a particular direction with varying degrees of power (some shots involve using the pace of the ball, like the ramp shot, the paddle sweep or the steer, while others, like the slog sweep or the square cut, involve high bat speeds). Second, they can either leave the delivery or merely block or defend it.

In the table below, where teaminnings in the IPL from 2014 to 2024 are organised by scoring rate, the first category of shot above is considered an attacking shot. Note that wide balls are not considered here as a wide, by definition, is not within the batter's reach.

The striking thing about T20 in general, and the IPL in particular, is that there are only about five extra attacking shots played per 120 balls faced in an innings that produces ten runs per over (a score from 190-209 in 20 overs), than there are in an innings that produces seven runs per over (a score from 130-149 in 20 overs).

About 73 of the 103 attacking shots in a seven-runs-per-over innings are in control, while about 80 of the 107-odd attacking shots in a ten-runs-per-over innings are in control. Higher scores are a result of better control and the share of runs from false shots (runs scored where they were not intended) in bigger totals is smaller than it is in smaller totals in T20. Though this trend seems to reverse after about ten runs per over, note that scoring rates of 13 runs or more per over in an IPL innings are still exceedingly rare and so we cannot draw significant conclusions about this uptick. If the 2024 season is anything to go by, this is likely to change and it will become clearer whether or not this rise is significant.

Applying the same shot-categorisation rules to Test cricket over the same period, a Test innings in which the scoring rate is three runs per over includes 216 attacking shots per 80 overs, while a Test innings in which the scoring rate is five runs per over includes 284 attacking shots per 80 overs. Adjusted over 120 balls (or 20 overs), that's 54 attacking shots in an innings that produces three runs per over (i.e. a run rate of 2.5 to 3.5), and 71 attacking shots in an innings that produces five runs (4.5 to 5.5) per over.

The distinction between the two is leverage. In a Test match, the bowler can force the batter to defend. There is such a thing as a good line and length. In T20, the bowler does not have enough of this leverage. The outcome of a delivery depends on whether or not the chance the batter takes is successful. Preventing the batter from taking the chance and forcing the batter to either leave or block a delivery is not really an option.

When commentators and writers ask for "sporting pitches" in the IPL, what they're really asking for are conditions in which the batter's chance is less likely to come off. In other words, they're asking for the match to be chancier.

For instance, in the low-scoring match between Lucknow Super Giants and Mumbai Indians on April 30, Mumbai batted first and scored 144 for 7. They played 35 false shots, which brought them 20 runs. In the chase, LSG made 145 for 6 and won with four balls to spare. They played 30 false shots which brought them 28 runs. One in six runs in this match came from a false shot. The difference between the runs scored from false shots made up 5.5% of the target.

Data suggests that the impact-player rule has caused a decline - though fractional - in the role of allrounders•BCCI

Four days earlier, on April 26, Punjab Kings chased 262 against Kolkata Knight Riders with eight balls to spare. They collected 29 (off 29 deliveries) off false shots, while KKR colleged 38 (49 deliveries) from false shots; KKR's innings included 11 extra deliveries). The gap between the runs from false shots was 3.4% of the target, and one in eight (12.8%) runs in this match came from a false shot.

In the longer forms of the game, the bowler has enough leverage to force the batter to defend at least some lines and lengths, because dismissals are sufficiently significant that the batter is not prepared to risk their wicket beyond a point. In T20, the bowler does not have such leverage. The balance between bat and ball is affected only marginally by factors like the condition of the pitch, the weather, the size of the ground or the quality of the bowling. This is why R Ashwin has argued that wickets are not taken in T20, they happen. How likely a batter is to defend depends on the state of the match rather than the line and length of the delivery.

There isn't much of a contest between batter and bowler in a T20, regardless of scoring rate. To create such a contest, the bowler's leverage will have to be increased significantly. This can be achieved in one of two ways. First, make it easier for the bowler to get a wicket by, for instance, allowing fielding sides to have 12 outfielders instead of nine. Second, reduce the resources available to the batting side by reducing the number of wickets available from ten to five.

Scoring Rates

The average 120-ball total in the 2024 IPL was 191. It did not exceed 180 in any previous IPL edition. Most of this increase has occurred during the powerplay. The impact-player rule was introduced in the 2023 IPL. Before this, the average runs scored in the powerplay ranged from 45 to 50. In 2023, this climbed to 52.3. And in 2024 teams scored 56.7 runs per 36 legal deliveries during the powerplay. Batters are hitting more fours and sixes and scoring between seven to 12 more runs in this short phase of the innings. The increase over the rest of the match after the powerplay is comparatively modest: 11 to 15 runs over 84 balls.

The average 120-ball total in the 2024 IPL was 191. It did not exceed 180 in any previous IPL edition. Most of this increase has occurred during the powerplay. The impact-player rule was introduced in the 2023 IPL. Before this, the average runs scored in the powerplay ranged from 45 to 50. In 2023, this climbed to 52.3. And in 2024 teams scored 56.7 runs per 36 legal deliveries during the powerplay. Batters are hitting more fours and sixes and scoring between seven to 12 more runs in this short phase of the innings. The increase over the rest of the match after the powerplay is comparatively modest: 11 to 15 runs over 84 balls.

A batter was dismissed every 18.5 balls in the 2024 IPL. This was about the same rate as in every other year. From 2014 through 2022, openers (batters at Nos. 1 and 2 in the order) in the IPL scored 59 runs in 44 balls on average. In 2023 this changed to 64 (45 balls). In 2024 the openers averaged 61 (39). In 2024, openers took fewer balls to score about as many runs they had as in previous IPLs. A similar pattern was evident in positions three and four. In 2014-22 they collected 49 (37) on average. In 2024, they made 54 (36).

It was apparent at the beginning of this decade that T20 openers were probably more conservative than they needed to be. Ten years ago, in the 2014 IPL, of the 38 players who opened the batting, the median opener scored at 116 runs per 100 balls faced and was

dismissed once every 22.2 balls. In the 2024 IPL, of the 35 batters who opened the batting, the median opener scored at 150 runs per 100 balls faced and was dismissed once every 19.9 balls. Much of the change has come from the increased frequency of six-hitting from the top order. From 2014 to 2022, a batter in the top four batting positions in the IPL hit a six every 20 balls and a four every eight balls. In 2024, such batters hit a six every 13 balls, and a four every seven balls.

The effect of the impact substitute

The impact substitute was used 136 times in 71 matches in 2024. Of these, 83 impact substitutes did not bowl, and 50 impact substitutes did not bat. Eight batted and bowled. Five did not bat or bowl.

The impact substitute was used 136 times in 71 matches in 2024. Of these, 83 impact substitutes did not bowl, and 50 impact substitutes did not bat. Eight batted and bowled. Five did not bat or bowl.

On the batting side, the impact substitution was successful in the top order (Nos. 1-3), and in the lower order (positions Nos. 7-9), but not in the middle order. Top-order impact substitutes produced 882 runs for 32 dismissals in 570 balls faced - a strike rate of 154.7 runs per 100 balls faced, and an average of 27.6 runs per dismissal. Lower-order impact substitutes produced 377 runs for 21 dismissals in 244 balls - a strike rate of 155 runs per 100 balls faced, and an average of 18 runs per dismissal. Impact subs in the middle order produced 322 runs for 20 dismissals in 299 balls - an average of 16.1 and scoring rate of 107.7.

Of the 54 substitutions made at the end of the first innings, 18 substituted players were batters, while 36 were bowlers. The replacement batters produced 461 runs for 17 dismissals in 290 balls (average 27, strike rate 159). The replacement bowlers conceded 1074 runs for 37 wickets in 669 balls bowled - 9.6 runs per over, 29.0 runs per wicket.

In the 82 substitutions made during an innings, 70 of the replacement players batted (1128 runs, 56 dismissals in 830 balls - an average of 20 and scoring rate of 136) and 17 bowled (12 wickets, 467 runs conceded in 250 balls - 11.2 runs per over, 38.9 runs per wicket). Of these, the bowlers ended up batting ten times, managing 56 runs and being dismissed six times in 40 balls.

Bowlers who came in as impact subs went for 10.1 runs per over vs the 9.4 runs conceded by bowlers in the original XI•BCCI

It has been suggested that one of the effects of the impact substitute rule has been to reduce the role of allrounders in an IPL XI. The evidence suggests that this is partly true. Of the 11,727 individual match contributions (batting or bowling) in the 22 IPL editions 2014 through 2022, 2964 (25.2%) involved both batting and bowling. In the 2023 and 2024 IPLs, this reduced marginally to 710 out of 3330, or 21.3%

The rules allow the impact substitute to be used to extend the batting order without eating into the bowling order. For instance, if a team is reduced to 30 for 4, it can replace one of the batters who has been dismissed with another specialist batter, and this specialist batter can bat at No. 6, leaving the bowling line-up unchanged. Similarly, the bowling order can also be extended by replacing a bowler who has already bowled two overs with a replacement bowler during a bowling innings. The replacement bowler can bowl four overs.

Impact subs collectively batted 1120 balls and bowled 919 in the 2024 IPL, conceding 10.1 runs per over and scoring at 142 runs per 100 balls faced. The players who were selected in the original XI conceded 9.4 an over and scored at 152 runs per 100 balls faced.

The impact substitute is a misnomer in many ways. The first-choice XI still tends to include the best available batters and bowlers. Impact substitutes tend to be the reserve batter or the reserve bowler whose returns are not as good as those of the players in the original XI. They extend the batting and bowling order, but do not necessarily improve it, especially on the bowling side, since the four-over quota means that regardless of the impact-substitute rule, teams must start a match with at least five bowlers, who they expect will bowl four overs each. If teams were allowed to name their XI and possible impact substitutes after the toss instead of before it, this will change.

Kartikeya Date writes the blog A Cricketing View. @cricketingview