A formidable quintet

Tanya Aldred sums up the contributions made by some greats of the women's game

Tanya Aldred

Apr 15, 2014, 12:00 AM

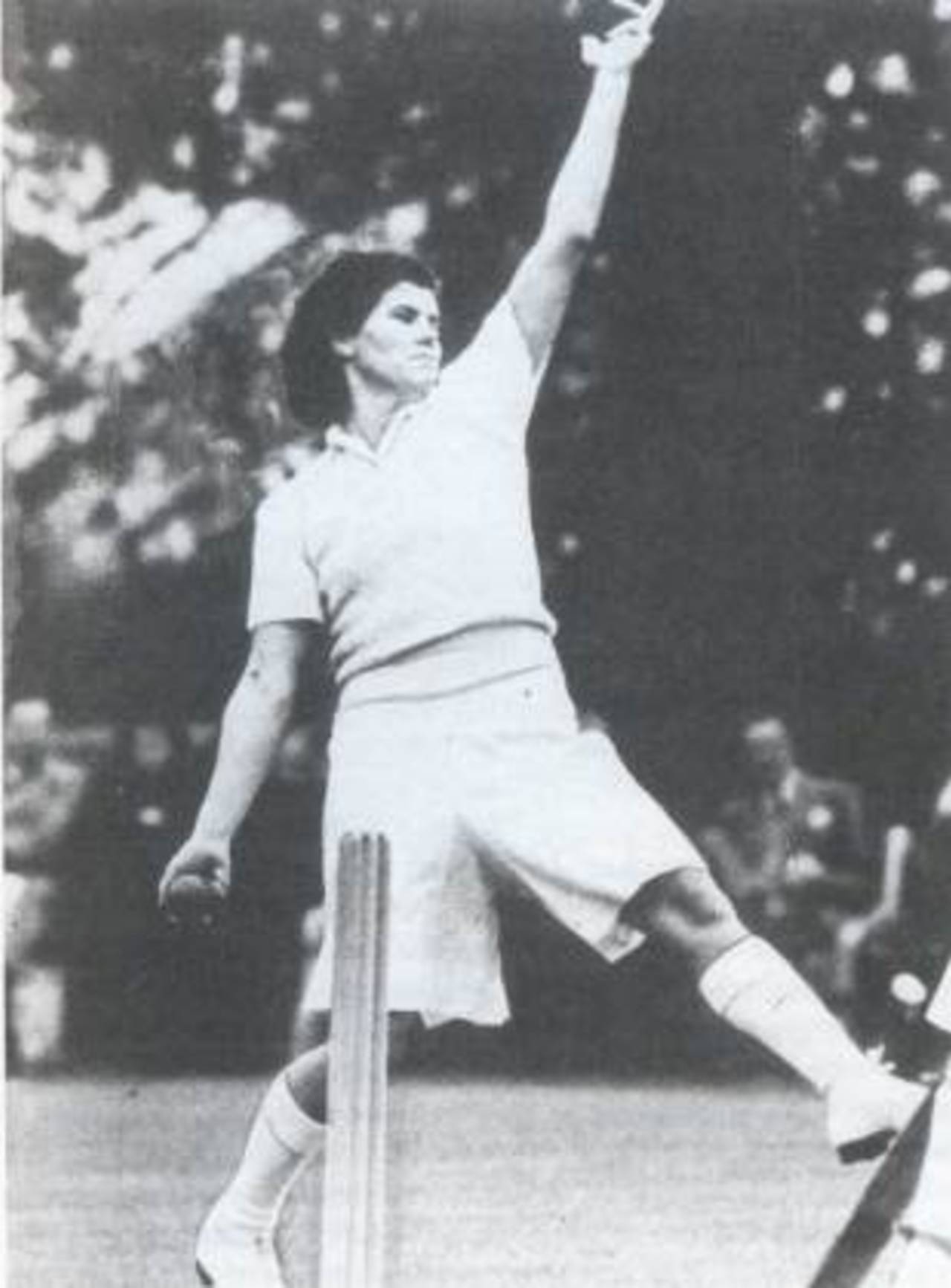

First love: Betty Wilson, bowling for the Australians against Kent at Sevenoaks, put the 1951 tour of England ahead of her personal life • AWCC

It has been almost 80 years since two art students, two office workers, a lawyer, an army auxiliary, two ladies of leisure and seven teachers sailed from Tilbury docks to Australia for the first women's Test, starting at Brisbane's Exhibition Ground on December 28, 1934. To celebrate those decades of dedication, bloody-mindedness and no little courage, Wisden has picked its five greatest female cricketers.

The process of whittling the candidates down was thorny. How do you compare performances in Test cricket, one-dayers and Twenty20? How do you

judge pioneers and semi-professionals, those who are supported by their board, or have largely gone it alone? How do you weigh up performance on the pitch against groundbreaking work off it?

There are many names missing who deserve to be honoured, not least Rachael Heyhoe Flint. You could easily come up with another equally worthy

five. And, in ten years' time, with the women's game set to evolve more quickly than ever, the list could look more different still. But those in this one

- three Australians, an Englishwoman and an Indian - played mostly for nothing, except enjoyment. They make a formidable quintet.

Betty Wilson

One Thursday evening in 1932, Betty Wilson pottered down to Collingwood Women's Cricket Club in Melbourne with her father. She stood on the boundary for a while, fielding balls and throwing them in. Her arm was so good that she was persuaded to join. Three days later, wearing a borrowed dress shortened especially by one of the players, she made her debut. She was ten. By 16, she was playing for Victoria and, although her ten-year international career was delayed the Second World War, she would became a bona fide superstar, who discarded convention to play the game she loved.

One Thursday evening in 1932, Betty Wilson pottered down to Collingwood Women's Cricket Club in Melbourne with her father. She stood on the boundary for a while, fielding balls and throwing them in. Her arm was so good that she was persuaded to join. Three days later, wearing a borrowed dress shortened especially by one of the players, she made her debut. She was ten. By 16, she was playing for Victoria and, although her ten-year international career was delayed the Second World War, she would became a bona fide superstar, who discarded convention to play the game she loved.

During the 1950s, Wilson was known throughout Australia, drawing crowds of thousands. She was nicknamed the female Bradman, averaging over 57; like him, she preferred to keep the ball safely on the ground. She was able to throw from the boundary of the MCG straight to the wicketkeeper, and for good measure bowled testing spin, turning the ball both ways and taking 68 wickets at under 12. Against England at Melbourne in February 1958, she became the first player of either gender to take ten wickets - her figures were 11 for 16 - and score a century in the same Test.

Wilson was a born sportswoman, athletic and fast. Her dedication was even more special: in an era when female cricketers trained once a week, she trained every day. She would throw stones flat and long, taking the heads off daisies, and bowl for hours in the nets at marks representing different batsmen. And, in a ritual learned as a girl, she would place a ball in one of her mother's stockings, attach it to the washing line, and hit it repeatedly with a bat, sharpening both her eye and her blissful footwork.

ELIZABETH REBECCA WILSON was born on November 21, 1921, the second of four children. Her father was a bootmaker who would fashion her

special lightweight bowling boots, and her mother ran a busy, happy home. Little Betty was a jumping bean, playing in the street for hours. She left school at 13 for a business course, and would do secretarial jobs all her working life.

When at last cricket resumed after the war, she made her debut against New Zealand at Wellington. She hit a speedy 90 and took ten wickets. In her second Test, she became the first Australian woman to score a century against England (there were nine more wickets, too). She seemed unstoppable. She never married. Her fiance´ twice agreed to postpone the wedding because of cricket commitments but, when Wilson decided to tour England in 1951, that was the end of the relationship. There was no contraceptive pill, and she needed more than home-making. "It depended what you wanted out of life," she told the National Library of Australia. "Who was going to knock a chance to go to England and play cricket? No. No way." The team sailed to Southampton; on the way she learned, among other things, how to peel an orange in company.

At the end of that tour, in which she scored 571 runs and took 57 wickets in 14 matches, she stayed on to see the country. She hung around long enough to have a grandstand seat at King George VI's funeral in February, and made friends she wrote to for 50 years. On the boat back she was devastated to learn her father had died. She cared for her mother for many years afterwards.

Her final series was England's tour of 1957-58. In the Second Test, at St Kilda, she scored that century and took those 11 wickets, on a damp pitch, including a hat-trick: "Off-break, leg-break, straight ball." She was so overwhelmed she burst into tears. She became a champion bowls player in her dotage and continued to support women's cricket, often to be found sitting in the MCG stands, her big white hairdo proud like a huge Mr Whippy. "She was funny," says Cathryn Fitzpatrick. "She didn't hold back. I remember her telling one of the girls to button her shirt up. She'd throw her head back to laugh. Her joy came from watching us play." When Betty Wilson died, aged 88, on January 22, 2010, she was acclaimed the finest of all female cricketers.

Enid Bakewell

In the winter of 1968, a vivacious part-time PE teacher was plucked from domesticity and sent to the other side of the world - she returned with 1,031 runs, 118 wickets and a twinkle in her eye. She had found her forte, and England their all-rounder. In her first Test, against Australia, Enid Bakewell opened the batting and made a century. Against New Zealand, seven weeks later, she made a century and took five wickets. And in the next, it was a century, five wickets, and a fifty that included the winning runs with just four minutes to spare.

In the winter of 1968, a vivacious part-time PE teacher was plucked from domesticity and sent to the other side of the world - she returned with 1,031 runs, 118 wickets and a twinkle in her eye. She had found her forte, and England their all-rounder. In her first Test, against Australia, Enid Bakewell opened the batting and made a century. Against New Zealand, seven weeks later, she made a century and took five wickets. And in the next, it was a century, five wickets, and a fifty that included the winning runs with just four minutes to spare.

Small but indomitable: Enid Bakewell averaged almost 60 in Tests•The Cricketer International

She was speedy between the wickets, nimble of footwork and dashing with the bat; her left-arm spinners were patient and had enviable flight. She was small but indomitable, smiling but deadly accurate. On her return, she found herself a minor heroine, and received a civic reception from

Nottinghamshire County Council and the Lord Mayor of Nottingham. Thirteen years later, she retired with a Test batting average of nearly 60, as well as 50 wickets at 16, and a stash of records.

ENID BAKEWELL (ne´e Turton) was born on December 16, 1940 in the Nottinghamshire pit village of Newstead. Her Methodist parents were in their

forties when she was born, her father a miner who would return home from a shift with coal dust stuck fast about his eyes. The village was patriarchal, but young Enid did as she pleased. She ran about with the boys, had her own pair of football boots, and would play cricket outside until dark on a pitch that she and the other children cut from an unused field using scissors and hedge shears.

Her parents had no real interest in the sport, but Enid loved it. She filled a desk with press cuttings on Tony Lock and Peter May, listened to games on

the wireless, and learned the fielding positions from a diagram in the Radio Times. At junior school, girls played hockey. Hitting the ball to the right wing used the same action as a cover-drive, so she got lots of practice. By 14 she was playing for Nottinghamshire, mostly as a batsman - it was not until her early twenties that she developed her spin. She went on to train as a PE teacher at Dartford College, where she played alongside Rachael Heyhoe (the Flint would come later). In 1959, she was picked to play for the Women's Cricket Association against the Netherlands on huge doormat wickets, but had to wait until that winter tour of 1968-69 before winning her full cap. By then she was married to Colin Bakewell, and was desperately torn about leaving her toddler Lorna. In the end, Lorna stayed with Enid's parents, who told her that mummy would be back when the flowers started blooming. Spring came early that year and, when she returned, Lorna had developed a temporary stutter. But modest, bubbly Enid had launched a magnificent career. She was showered with gifts, including a dressing-table set from Kirkby Council, and received them with thanks. It was expensive to play (culottes alone cost seven guineas), and Colin kept a tight grip on the purse strings.

She went on to have two more children, Lynne, named after her opening partner, Glamorgan's Lynne Thomas, and Robert. Enid enjoyed one-day

cricket, scoring a century in what effectively became the first World Cup final, in 1973, and 50 in the first women's international at Lord's, in 1976. Her pie`ce de re´sistance came in her final Test, against a hostile West Indies in 1979, in which she became only the second person, after Betty Wilson, to take ten wickets and score a century in a Test - she carried her bat in England's second innings for 112 out of 164. She was barely off the field all match.

Now in her seventies, she walks, swims and plays bowls, though no longer deliberately makes herself so late for the bus that she has to run. She enjoys a game of Candy Crush on her tablet, stuffs envelopes for the Labour Party and does 4,000-piece jigsaw puzzles: her patience, determination and competitiveness remain undimmed. She continues to turn out for her old team, the Redoubtables, opening the bowling. People, she says, still play her reputation. Cricket has been the love of her life, "a social breaker of barriers" - just as she was, this coal miner's daughter who became England's greatest female all-rounder.

Belinda Clark

Until she was 16, Belinda Clark wanted to win Wimbledon. Thump, thump, thump went the ball against the garage door; thump, thump, thump against the big brick wall at Hamilton South Primary School in New South Wales. Day after day she would be there by 7am, dressed in her brown, yellow and white checked dress, racket in hand, until eventually the worried school phoned home to ensure everything was all right.

Until she was 16, Belinda Clark wanted to win Wimbledon. Thump, thump, thump went the ball against the garage door; thump, thump, thump against the big brick wall at Hamilton South Primary School in New South Wales. Day after day she would be there by 7am, dressed in her brown, yellow and white checked dress, racket in hand, until eventually the worried school phoned home to ensure everything was all right.

She never did get her hands on the Venus Rosewater Dish, but she did achieve almost everything in cricket. She made the Australian team at 20, and

became captain at 23, leading them in 11 Tests and 101 one-day internationals, where her win-rate was over 80%. She lifted two World Cups. She was the first player, male or female, to make a double-century in a one-day international.

She opened the batting, averaged over 45 in both forms of the game, and was named Cricketer of the Year in the first edition of Wisden Australia, in 1998. And all of this while holding down demanding jobs, first as chief executive of Women's Cricket Australia, then as their women's cricket operations manager.

Flashing blade: Belinda Clark drives Australia to victory over South Africa in the semi-final of the 2000 World Cup•Photosport/ESPNcricinfo Ltd

BELINDA JANE CLARK was born on September 10, 1970, the third child of four. The family moved to Newcastle when she was five, and she spent her childhood hitting balls, getting dirty, climbing trees and copying anything that her brother Colin did. It wasn't until she was 12 that she had any idea a woman could play cricket for Australia. From there, things progressed quickly. At Newcastle High School she played local, state and Australian indoor cricket, and outdoor cricket for the girls' team, and was fast-tracked into New South Wales Under-18. She already had a remarkable work ethic, passed down from her parents, Margaret and Allan: "I expected myself to win. They expected me to do my best, behave properly and give it a good shot."

She trained to be a physiotherapist, but in January 1991 was picked by Australia, scoring a century against India on Test debut. She was a technically

brilliant, attacking, classical batter. Within three years, she was made captain. Being a young girl in charge of an experienced team could have been difficult, but she made it work. The side were in flux, and she remoulded them with the coach, John Harmer. She expected discipline, aggression and excellence - and got them.

"I played with a group of people who were very driven," she says. "As captain I wanted to ensure that the Australian team trained with intensity. I always believed my preparation was better than anyone else's. I had confidence in my ability and faith in my technique." Her greatest experience was winning the World Cup at Eden Gardens in 1997, in front of a fervent 65,000. She considers her best innings the 142 off 130 balls she made against New Zealand in February 1997, after she had accused them of playing boring cricket. It was the sort of forthright opinion she learned to keep to herself.

As she grew older, she became more risk-averse; managing her mind became harder. She retired in 2005, after losing the Ashes in England but

winning the one-day series, and landed a job as the first female head of what is now the National Cricket Centre, where she is currently in charge of the whole women's programme and the men's, up to and including Australia A. She enjoys it, although she misses the old freedoms. "I spend a lot of time sitting in a chair, talking to people, sandwiched between layers of management. It is a different challenge."

She has never played cricket again, even though she yearns for the physical sensation of watching the ball, then hitting it. It was time to move on. Instead, she swims and runs, and has completed two marathons. At home she has some memorabilia tucked away - the stumps of her 100th game, some old bats (though one of them sits in the Australian fielding practice bag). Her baggy green is in the Bradman Museum. Her cover-drive should be too.

Cathryn Fitzpatrick

For 16 years, off a run that was trimmed from 17 steps to 13, Cathryn Fitzpatrick scared people. Her blond mop bothering the air, she bowled spitting outswingers. No woman has taken more international wickets; no woman bowled faster. From just 5ft 6in of solid muscle came 5oz bullets at 75mph. The highest one-day international wicket-taker in the world, with 180, she also managed 60 in just 13 Tests. She helped Australia to two World Cups, and spearheaded one of the greatest female teams of all time.

For 16 years, off a run that was trimmed from 17 steps to 13, Cathryn Fitzpatrick scared people. Her blond mop bothering the air, she bowled spitting outswingers. No woman has taken more international wickets; no woman bowled faster. From just 5ft 6in of solid muscle came 5oz bullets at 75mph. The highest one-day international wicket-taker in the world, with 180, she also managed 60 in just 13 Tests. She helped Australia to two World Cups, and spearheaded one of the greatest female teams of all time.

The whirlwind flies in: Cathryn Fitzpatrick bowls against New Zealand in February 2004•Getty Images

CATHRYN LORRAINE FITZPATRICK was born in Dandenong, Melbourne on March 4, 1968. The youngest of three, she grew up kicking around

with her brother Gary's friends, messing about with tape on a tennis ball, learning how to control a seam. She was 11 when she played her first

competitive game - there were no girls' teams, so it was in an open-age tournament. On Saturday mornings she would pull on her culottes, go to the

local milk bar and wait for a lift to the nearest match. She was a whirlwind, "a fast bowler of no use to anyone", she says, but utterly smitten. Her brother grew less keen on facing her in the front yard, but she and her grandfather, Cliff Hill, would constantly talk cricket. By the time she was 16, she realised people were shying away from her in the nets.

She played junior cricket for Victoria, but it was not until she was almost 23 that she made her debut for Australia. It was uneventful, and she was dropped for a couple of years. The man who located her inner sonar was women's coach John Harmer. He wanted the fastest bowlers, and so he wanted Fitzpatrick. He made her action safer and more repeatable. Out went the tangle of arms and legs, in came a smoothness, a more consistent release point, and greater tactical awareness. She became a supreme technician, delivering metronomic crimson crotchets, at a beat, on command. She loved it when the ball was thrown to her in pressure situations. It often was. Her strategic nous grew, and she built up her fitness, muscle by muscle, with a succession of physical jobs. She ran behind the garbage truck for six years, wrestling with bins, and later delivered letters for Australia Post, first on a bicycle, then on a scooter. These early-morning jobs gave her extra training time in the afternoon. The supreme machine needed constant oiling.

As the clock ticked, her pace dropped a little, but not her guile. And when she at last retired, at 39, after a 16-year international career, she was still one of the fittest in the team. She had spent two years as the scholarship coach at Cricket Australia's Centre of Excellence, ruffling a few feathers, and in June 2007 was appointed coach of the Victorian women's team. She led them to three Twenty20 titles and, when she took over as head coach of the national side in 2012, she helped guide them to 50- and 20-over World Cup triumphs.

She enjoys the different challenges: "Girls want to know why, more than boys." Her self-effacing manner and quietness belie an inner strength - which

the team feed off. She ensures they know about their heritage and the battles won. She still bowls sometimes in the nets, off-breaks that don't do anything, and gives plenty of needle.

But the body isn't quite as reliable as it was - sore shoulders where she once hefted bins and parcels, a couple of knee operations, a disc bulge in her back. "I'm 45, and in the morning I bend down to pick up the cat and I can't stand." There never was, until late in her career, any recompense. She had to pay to tour, a double whammy since this meant unpaid leave. She felt less like a pioneer and "more like a whinger - we were always advocating change, striving to be the best we could. But it meant we changed the game."

Mithali Raj

Great cricketers love what they do. Don't they? Mithali Raj is different. For years, she excelled in something she didn't particularly enjoy. "It took me a really long time to love cricket," she says. "I played it more out of curiosity and to prove to my dad that I was good. I cemented my place and developed a reputation, but it wasn't until really late, 2009, that I actually started loving the game."

Great cricketers love what they do. Don't they? Mithali Raj is different. For years, she excelled in something she didn't particularly enjoy. "It took me a really long time to love cricket," she says. "I played it more out of curiosity and to prove to my dad that I was good. I cemented my place and developed a reputation, but it wasn't until really late, 2009, that I actually started loving the game."

By that time she had made what was then the highest score in women's cricket (214) in only her third Test, and led India for five years, including to

the World Cup final against Australia in 2005. She is consistently ranked the best one-day batsman, having made more than 4,600 runs; despite limited opportunities she has a wonderful Test record. And all this for a constantly rejigged team and under the gaze of a strangely half-hearted BCCI. In a country where cricket is an obsession, women's cricket is thistledown on the wind: Raj has a barely-there commercial profile and a tiny social-media following, and is virtually unknown outside cricketing circles.

Double top: Mithali Raj darts towards her record-breaking 214 at Taunton in 2002; the England wicketkeeper is Mandie Godliman.•Getty Images

MITHALI RAJ was born on December 3, 1982, in Rajasthan, where her father, Dorai, was enjoying his last posting in the air force. She was a solitary

but happy little girl, whose passion was Indian classical dance, Bharatanatyam. When she grew up she wanted to be a dancer; her mother, Leela, agreed. But Dorai had other ideas. He was a disciplinarian, and disliked Mithali daydreaming and getting up late. When she was nine and a half she was sent to a cricket camp during the summer holiday with her older brother, Mithun. She had never picked up a bat before, but the coach saw something in her, and when she went back to school she joined the girls' team. Along the way, she met her favourite coach, the late Sampath Kumar.

For a while she was able to combine dancing and cricket, but in 1997, aged 14, she was picked as first standby for the World Cup. She had to make a

decision. Dance classes had already given way to net sessions and, after much thought, she chose cricket. "It wasn't easy. Dance came naturally to me.

Cricket happened to me." The choice went down badly with her extended family, who were upset that she continued to miss family functions. "Perhaps it was hard for them to understand, perhaps they thought that a south Indian girl should be homely, learning cooking and things like that."

She played for Hyderabad age-group teams, as a medium-pace new-ball bowler and opening batsman, and in the domestic competition for Railways,

who still employ her off the field. In June 1999, on her one-day international debut against Ireland at Milton Keynes, she made an unbeaten 114. Three

years later, she was back in England, in the more bucolic setting of Taunton.

The tour had been a shambles, and her double-century became the shining light. She had no idea she had beaten the world record until the twelfth man

was sent on to whisper in her ear. Her overriding feeling was exhaustion. She was 19. Her strengths are her touch and timing, a calmness at the crease, and an awareness of what is going on around her. She loves to grab the game and change its course, though the responsibility of being the middle-order rock leashes her in. She has led the team on and off for ten years, and guided them to their first Test victories over England, in 2006, though she doesn't consider herself a natural captain. Experience has helped, and she enjoys passing on her knowledge to the younger women. Her biggest frustration is the lack of regular cricket. Now in the twilight of her career, she is desperate to guide India back to the top table after their disastrous 2013 World Cup at home.

In a sense she already belongs to a passing generation: she prefers one-day cricket to Twenty20, and wishes she could play more Tests. She is happy in her own company, and in her spare time she reads and sketches. She doesn't watch cricket. She is a woman apart and, in her own way, a trailblazer.

Tanya Aldred is a freelance writer in Manchester