The Archie Jackson story

|

|

|

It hit me just about as hard as Archie did that day at Adelaide in 1929 when, in his first Test innings for Australia, with 97 runs against his name and having had his back to the wall, he cover-drove me to bring up his hundred. That ball was delivered as fast as any I had ever bowled previously.

That glorious stroke has lived in my memory to this day for its ease and perfect timing. I am sure that few among the many thousands present sighted the ball as it raced to the boundary.

I personally had a very great admiration for Archie, and I am sure we `Poms' counted him as one of us. He never failed to congratulate the bowler or fieldsman whenever he was dismissed by a good ball, and at the same time he would be the first to let you know when he thought you were not bowling so well. He would say: `You must have had a late one last night, Harold!'

He was always friendly, no matter the tenseness of the situation - you just had to find a place in your heart for a fellow like him. The respect he showed for others grew on you.

I remember once, in England during the 1930 series, in scoring 73 at the Oval in the fifth Test, he was taking quite a physical beating. As he came down the wicket to level a high spot or two he said: `Well, Harold, it's only a game, but what a grand one we're having today! I hope you're enjoying our battle as much as those spectators seem to be. You know, you've hit me almost as many times as I've hit you! I wish you'd drop one a little off line occasionally.'

I never knew him to flinch or complain at any time.

No, Archie Jackson, like his hero Victor Trumper, was born to be great, and great he was, for he received the same respect from us `Poms' as from his own team.

But we had a feeling that something was amiss with this young fellow in 1930. Those of us who were closely associated with him knew that the English climate did not suit him; he was not himself. He still batted with the same charm that only he was capable of, but it was apparent that he was not the same Archie as that of 1928-29.

One of my most cherished possessions to this day is a personal telegram sent to me by Archie while undoubtedly a very sick boy in Brisbane; it congratulated me on my bowling in that controversial Test of 1933. At the time he must have been very close to meeting his Maker, but he was still conscious enough to remember an old friend.

I remember also a number of us Englishmen visiting Archie in the private hospital in Brisbane one afternoon after practice before the fourth Test. It was the last time we were to see him, for during the final stages of that Test match he passed away. We felt the depression that was cast over the ground when early that morning the news came through that Archie was no more.

It was hard to believe. We knew that our loss was Australia's also. Privileged were those who had known him. I for one could never forget Archie Jackson.

Adapted from The Archie Jackson Story by David Frith, published in 1974 in a limited edition of 1000, and out of print since 1975.

There is a love - and usually a sadness - at the heart of a cult. Victor Trumper was the first tragic hero of Australian cricket. His failing health robbed him of untold hours in the sun, and though his death in 1915 did not shorten his international career, the loss of his maturity, the years of fullness when a veteran spreads himself in relaxation and reminiscence, was grieved. He was humble and kind; he deserved a long life. All who knew him believed this.

The dreamy Alan Kippax, who mirrored Trumper, had an extensive and loyal following during the 1920s and 1930s, but in an era when his finesse was mistrusted by Test selectors he left his lyrical style in the memory and assumed, in the eyes of the world, a stature undeservedly less than major; the book of figures tells but one side of his story.

At his zenith Kippax, welcomed into the ranks of the New South Wales team a slender, athletic lad who, though never having seen Trumper, possessed all the comely movement and keenness of eye of Sydney's God of Cricket. His exceptional talent had proclaimed itself at a precocious age, and cricketers all around him watched expectantly as Archie Jackson's promised gift grew to fulfilment.

This was the beginning of a cult. Men of all ages who saw him never forgot him, and a generation later they still held his banner. All those who had made his acquaintance shared the desire to be regarded as his intimate friends.

Jackson was to bear uncomplainingly an insidious sickness that racked him for years. He disdained treatment, perhaps in disbelief, perhaps in valiant optimism.

When - the last of the line - he died at 23, cricket's transition from an aesthetic exercise to a purely mathematical strategy was under way. His influence was missed very seriously. No spectator could ever have watched him late-cut or advance to the drive without having to stifle the temptation to imitate.

In such premature death there is a danger that the legend becomes gilded: that is not the case here. A wealth of evidence substantiates the expectation and eventual manifestation of Jackson's splendour.

The wider tragedy, apart from the pity that avid England only ever saw a faint shadow of the man, is that during the businesslike 1930s there was no Archie Jackson to provide a model and an inspiration to youthful cricketers in both countries. Kippax played halfway through the decade and made many graceful hundreds, but his peak had been around 1926, when 21 of his 22 Australian caps were still to come. Two savage blows to the head had also upset him irretrievably.

The decade - for Australia- was dominated by Bradman, Ponsford, Woodfull, and McCabe, all except the last having a predictable near-infallibility. Jackson might have continued to add a touch of Dresden.

Or he might have tightened up as the seasons passed, unable, even by repeating his follies, to recapture his artistic youth. But I doubt it.

A telephone call got things under way: `Bill Hunt, the cricketer?'

`That is so.'

I introduced myself. `I understand from Alan Kippax that you were a close friend of Archie Jackson's?'

`May I say that no-one knew him better.'

So began the reconstruction of a career. I pored over Bill's scrapbooks and filled notebooks as reminiscence played itself out. He introduced me to Jackson's two sisters and they in turn referred me to his former fiancée. I began to see the subject from other angles.

Walking the streets of Balmain, standing outside his childhood home, talking with elder sister Peggie in the house in Drummoyne to which the family later graduated, finding his grave at the Field of Mars Cemetery, seeking out old team-mates and adversaries - I found that the young man's spirit lived still.

Unexpectedly, I obtained access to a number of Jackson's letters, most of them full of hope and rationalisation, written with candour to some of his friends during the last five years of his life.

|

|

|

The casual elegance of his leg glances, the whalebone suppleness of his wrists as he steered the ball square and backwards, the lightness of footwork, the ballet-like inclination of the body as he cover-drove - the artistry, enhanced by a beguiling self-consciousness, burned an impression on my mind.

The demonstration had been more than adequate. The only surviving film of Trumper is an abrupt and cruel misrepresentation of his magical technique, but for five enchanted minutes I had had the great good fortune to see a faithful image of his spiritual descendant.

I found myself aligned with all those thousands who, having seen Jackson batting, sighed for more when he was dismissed.

Archie Jackson, like Adam Lindsay Gordon, Billy Hughes (`the Little Digger'), Russell Drysdale, Frank Ifield and a number of other famous Australians, was born on the opposite side of the world. The Jackson family lived at 1 Anderson Place, Rutherglen, south of Glasgow, when Archibald arrived on September 5, 1909. Margaret and Alexander already had two daughters: Lil, aged five, and Peggie, three.

`Sandy' (father Alex) was manager of a brickworks at Belvedere. He had been taken to Australia in a sailing ship with his parents when he was 12, but returned to Scotland five or six years later. Now, as a 41-year-old working man with responsibilities, he eyed NSW thoughtfully once more. Times were tough in Glasgow.

Thus Sandy struck out again for Australia and paved the way for Mrs Jackson and the children to follow 18 months later. Themistocles, soon to be sunk in the First World War, landed them safely in Sydney on August 1, 1913.

The family set up house in the tilting, rambling old waterside suburb of Balmain: at 14 Ferdinand Street, a small, cosy, iron-roofed, terraced house, built in two storeys of brick, with a laced-iron balcony. It still stands.

After the War the family was completed by the birth of Jeanie, a precious sister for the other girls, and for Archie, whose early disapproval at not getting a baby brother soon evaporated.

`Don't leave her outside in the pram,' he often pleaded. `Someone'll take her away!'

He spoilt Jeanie more with each passing year.

There was never much money about, and Archie had to make do with one pair of pants for the greater part of his boyhood, the sole advantage being that his mother could withhold them whenever he was forbidden from going out.

But the home felt secure and was happy. Sandy worked at Cockatoo Dockyard and gave the rest of his time to his family. He put rubber bars on Archie's worn shoes and they served as soccer boots; he made a bat for him to use in the street games, both by day and under the illumination of the gas lamps - not merely a carved plank, but a realistically-shaped implement with a cane handle. He earned in return a tender adulation.

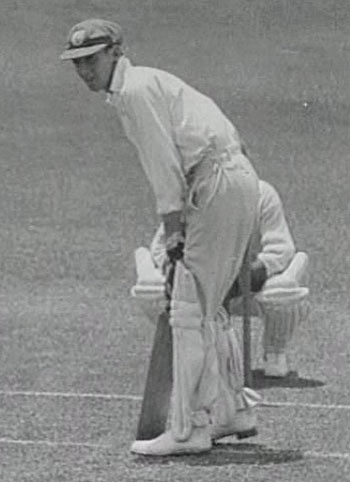

Tousle-headed mite Archie outside the Jackson home at 14 Ferdinand Street, Balmain. A regular sleepwalker, he once almost fell from the balcony. The shape of Test cricket would have been altered slightly

`Isn't that your boy, Sandy?' said a work-mate one afternoon as a rowing boat floated past the Dock with a small figure lying face-down to avoid recognition. The lad explained that evening that he had only wanted to see his Dad at work. The punishment for truancy was not severe.

The parents were usually good-humoured, too, when he returned with a sackful of apples filched from the orchard up at Mars Field. Other times he amused himself by riding the laundry cart through the narrow Balmain streets.

A well-remembered crisis was when he fought with school-mate Tommy Thompson through four consecutive afternoons before sister Lil felt bound to tell Mum, who went straight down to Birchgrove Park to break it up.

He was no angel. But he was loving, and he was greatly loved.

When Archie's school, Birchgrove, played cricket against Smith Street, he met Bill Hunt and began a lifelong friendship. They became pals during the 1920-21 season, when J. W. H. T. Douglas's MCC team were moving round Australia from one defeat to the next at the mighty hands of Warwick Armstrong, Jack Gregory, Ted McDonald, Charlie Macartney, Herbie Collins, Charlie Kelleway, `Nip' Pellew, Arthur Mailey- a formidable assembly of skills.

Archie idolised certain cricketers from each side, and he and Bill - when they were not satisfied to play `numbers cricket' out of the hymn-book in Bible class - had a resourceful manoeuvre for getting to the Sydney Cricket Ground. They `wagged' school at lunchtime, hopped onto a Wood Coffill hearse on its way back to the city, and used their threepence lunch money to get into the ground, where they quenched their thirsts at the bubbler at the base of the Hill, watched the international stars at play - wishing they could be out there too - and went hungry.

After play they usually hitched a ride on the meat wagon back to Balmain, where the mothers strove to fill their bellies.

`They talk about pollution in the 1970s!' said Bill Hunt 50 years later. `In those days the people of Balmain used to spread coal dust on their bread!'