Suddenly, everything went "Boom!"

Roland Watson

|

|

|

Funny things happened during the summer of 2005. Footballs disappeared from playgrounds. Families looking for a bat and stumps to take to the beach scoured shelves in vain. The Times put a cricket picture on its front page every day for a week. And a Lincolnshire man equipping his son for this new craze logged on to the internet, thinking cricket was like golf and that the boy only needed one glove. Cricket was indeed reaching those it had never reached before.

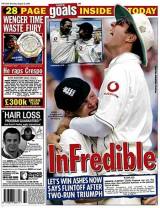

During the crazy weeks of the Ashes, newspaper headlines initially asked, then announced as fact, what became a widely accepted truth: cricket was the new football. That is to say, cricket was splashed on the front pages as well as the back, it topped the broadcast news rather than tailing it. The dinner table, the water cooler and the public bar hummed with the latest dramas of an ever-tilting series. Many who could not have named him a month previously started referring to the England captain as "Vaughany". Cricket, in other words, dominated the national consciousness.

The morning-after question for English cricket was twofold. First, was it real? Or, put another way, was the hysteria accompanying England's first Ashes victory for nearly two decades an understandable bout of late-summer euphoria or indicative of a significant shift? And, secondly, if the latter, could it last?

By almost any measure, the initial answer was that yes, England's onfield success had translated into a spectacular eruption of interest in the game. Participants at the sharp end, both coaching and commercial, described their worlds as going "bananas", "mad", "bonkers" or other variants on the theme of the roof blowing off.

Take bat sales. Woodworm, a fledgling firm, presented a microcosm of the madness. In the year to September 2005 sales had already rocketed to 15,000 from a mere 200 three years previously. But that was dwarfed by the 20,000 sold in the next seven weeks. Turnover trebled. The Woodworm story was exceptional, thanks to some brilliantly prescient marketing; the company paid Andrew Flintoff and Kevin Pietersen vast sums to endorse the brand.

But their experience was mirrored elsewhere. The Ashes helped Woodworm's 150-year-old rival Gray-Nicolls to a record year. Sales went up 20%, most notably in junior equipment. Shelves cleared at such a pace that the firm had to ship in extra supplies before Christmas: a first. Nor was it just the big names cashing in. Owzat-cricket, a shop and online store based off the M1 north of Derby, is neither a big name nor sited in a prime location. It would usually sell £150-worth of cricket kit on an autumn Saturday. But in 2005 it was shifting up to £3,000-worth, and needed two extra weekend staff. Andy Mitchell, the owner, bought 1,300 sets of bat, ball and stumps during the summer. They should have lasted two years, but were cleared out by the end of September. "You can't get a cricket set for love or money," he said. His sales of replica shirts were up tenfold. One November morning Mitchell logged on to his computer to find he had sold 91 bats overnight. "If I had sold one bat at this time of year two years ago it would have been a bonus," he said.

Fans found other outlets for their money. A cricket computer game went to the top of the charts. Travel firms organising overseas tours for fans reported unprecedented business. Gulliver Sports Travel, a leading operator for cricket and rugby tours, would expect to take 500-600 supporters to Australia on an Ashes tour. But before the 2006-07 Tests were even scheduled, they had received 2600 enquiries about places on tours costing up to £4500. Half of those had paid a £100 deposit.

Before that, ticket sales for the 2006 summer Tests and one-day internationals against Sri Lanka and Pakistan had got off to a roaring start. The first four days of the Oval Test against Pakistan sold out the day they went on sale. More tickets sold for the fifth day than at a similar stage for the final Ashes Test. More significant was Headingley, traditionally a much slower starter, where sales were breaking all records. The 20,000 tickets sold before December was double the norm.

Had English cricket been here before? Would the enthusiasm fade, quickly and inevitably? Compared with "Botham's Ashes" in 1981, the most obvious point of reference, the answers appeared to be: sort of; and not necessarily. In 1981, too, cricket had become the national discourse. In those pre-internet days, crowds gathered outside TV shops to watch through the windows. The excitement was unforgettable. Yet although both summers ended with Ashes victory, there were also significant differences. The dominant theme of 1981 was more the man than the cricket. There was an operatic, almost Greek quality to Botham's summer: the villain of Lord's, the pair, the hushed Long Room, the resignation as captain before he was pushed; and then the scarcely believable comeback.

In contrast, 2005 was a shared triumph rather than a succession of extraordinary individual exploits. The resonance went deep. At the beginning of the year, the ECB, with its sights on the game's profile, set itself a target of ensuring that three England cricketers were recognised by 10% of the population by 2009. Thanks to the Ashes, they claimed 12 in seven weeks. This appetite was reflected at grounds. In 1981, a mere 2,000 turned up to Headingley to witness England's astonishing final-day victory. In 2005, Edgbaston was full on the Sunday morning, even though England only required two Australian wickets to win.

And this time the spoils of public awareness (including the MBEs) were also shared down the order: players signed sponsorship deals with High Street stores and kitchen-table brand-names previously nowhere near their reach. Andrew Strauss, hardly an opener in the charisma stakes, struck a deal with Heinz. Even Gary Pratt, the substitute fielder who could not make the Durham first eleven, appeared in celebrity game shows.

|

|

|

Those involved at grassroots level believed the aftermath of 2005 to be notably different from 1981. Terry Holt, head of indoor cricket at Lancashire, was inundated with children wanting to get involved. Where 60 kids used to turn up to the Saturday club, 140 started arriving. Waiting lists for indoor courses were too long to join. Courses over the Christmas holidays booked up in October, rather than mid-December. Holt was involved in youth cricket in 1981; there was nothing like this then, he said. These children were not just coming from cricket clubs; they were coming from nowhere and everywhere.

Rob Brooks, head of PE at Lord Williams's, an Oxfordshire secondary school, had battled against the wind to maintain the cricket tradition. Now came the reward. At break-time early in the autumn term, all he saw were boys and girls shaping their bags into wickets. "You just don't see a football on the playground at the moment," he said. Instead of 20-odd from each year turning up for cricket training in spring 2006, he was hoping for up to 50. "The summer has reinvented the game and given it a much, much larger audience and profile. It was like a perfect film script."

It was a script that the ECB could not have improved. The board's fouryear national strategy to raise the game's profile, Building Partnerships, had been launched only three months before the series began. Another scheme, a Chance to Shine, an ambitious ten-year campaign to regenerate competitive cricket in state schools, was launched around the same time. The timing meant that, in some parts of the country at least, the seeds of Ashes enthusiasm had somewhere to germinate.

But would they flower? For the pessimist, the football World Cup in the summer of 2006 loomed large. Cricket would surely be wiped from the back pages, let along the front. Football would be the new football. The optimist, though, saw a relatively young England team. Retirements would not break it up imminently, as they did the England rugby team that won the 2003 World Cup, to the detriment of its public profile. The next Ashes campaign was only around the corner, closely followed by the cricket World Cup in early 2007. If Flintoff and co could surf the next 18 months, and especially if they could become the first English world champions, cricket would surely continue to broaden and deepen its appeal. But that was always going to be a very big "if ".

The losses in Pakistan may have dented England's pride and claims to be the new force in world cricket. But for the new cricket enthusiasts, the tour might as well not have been taking place. On December 2, as England were crashing to ignominious defeat in the Lahore Test, Andy Mitchell was also being forced to surrender: ceasing to take Christmas orders.

His backlog was so vast that he could no longer guarantee delivery before the 25th. An emergency shipment of 500 bats was on its way from India, and he had just quadrupled his staff - partly to give him time to be patient with his new customers. "Do you know what size bat your son wants?" "Does it matter?"