Scratching a living

Nick Newman

| |

It's as inevitable as a middle-order collapse or a Steve Harmison wide: sooner rather than later a cartoonist puts pen to paper and scribbles a drawing encapsulating the eccentricity, frustration, peculiarity, joy or sheer pointlessness of cricket. A game that can last five days without a result is an inviting target, even for those with no interest in it. And the jokes also work for those who find it a tedious mystery. Maybe it's the English character - to laugh at the things for which we are famous. Or perhaps cricket just provides endless opportunities to lampoon stuffiness and silliness.

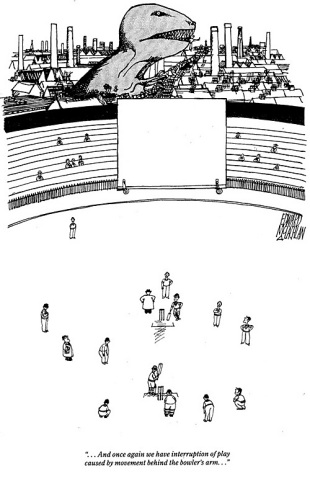

A personal favourite appeared in Private Eye in the 1970s. Ed McLachlan depicts a typical scene at a major, sparsely populated ground. Play has stopped, the umpire turns round in annoyance and an unseen commentator explains "…And once again we have interruption of play caused by movement behind the bowler's arm…" Except the movement is a giant Tyrannosaurus rex rampaging through the city, destroying buildings and gobbling people. In the world of cricket, global catastrophe plays second fiddle to the niceties of the game. The balloon of pomposity is held up - and pricked with sublime surreality.

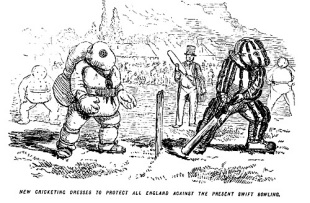

Cricket cartoons have a long history. One classic drawing shows a bizarre armour-plated and padded figure wearing what looks like a deep-sea diver's helmet - but wielding a bat - and is entitled "New cricketing dresses to protect All England against the present swift bowling."

It was drawn by John Leech and appeared in Punch as long ago as 1854, but the theme, if not the style, could have come from almost any decade. Similarly timeless are William Heath Robinson's ideas for cricket novelties, including the device below.

Completely oblivious to the existence of this cartoon, dating from the 1930s, I drew the selfsame joke about batting against Harmison only last year.

| |

Fougasse, a contemporary of Heath Robinson's, drew for Punch (and ended up as editor). The son of a notable cricketer, he was also an acute observer of the game. "Of course," says one Fougasse spectator to another, "there's one thing that no foreigner will ever understand, and that's our enthusiasm for cricket" - as he sits in a vast, empty stand… Plus ça change. Fougasse was best known for his economy of line in the "Careless talk costs lives" posters during the Second World War. But he perfectly captured the village cricketer in his "Charm of Village Cricket" character series for Punch: "Other things being equal," notes Fougasse, "if one hits the ball directly to a fielder in a cloth cap one can run a single - stretching it to three for a straw hat - and four for a black waistcoat - while for cuffs buttoned at the wrist - or a dickey, one just runs it out. With small boys in shorts," he concludes, "one naturally takes no chances whatever… - as everyone knows they are apt to become so confoundedly enthusiastic."

Village cricket, with its slapstick of dropped catches and run-outs and clichéd social mix of toffs and blacksmiths, has provided the bread and butter for gagsters down the years. But cricket has also provided an irresistible metaphor for political cartoonists. Sir David Low caused a furore in 1925 when a cartoon for The Star entitled "IT" caricatured Jack Hobbs, standing as a colossus beside the diminutive statues of Caesar, Lloyd George, Charlie Chaplin… and Mahomet. The Morning Post reported that in pre- Partition India the cartoon "convulsed many Moslems in speechless rage". Some feared there would be riots - a dramatic foretaste of the Danish cartoonists' controversy 80 years later, and a reminder of the enduring power of the pen. Less contentiously, the 1930s, 40s, 50s and 60s saw Low, Vicky and others drawing political figures being bamboozled and bounced out by the trade unions, their colleagues, the Opposition or the Lords. The 1970s, 80s, 90s and Noughties have seen Garland of the Daily Telegraph and others drawing… well, political figures bamboozled and bounced out by the unions, their colleagues, the Opposition or the Lords. Plus ça change indeed. "A treaty too far" (overleaf ) appeared in July 1992 during the debate on Maastricht, when the cricket-loving and vaguely europhile John Major was being undermined by the strongly eurosceptic Margaret Thatcher.

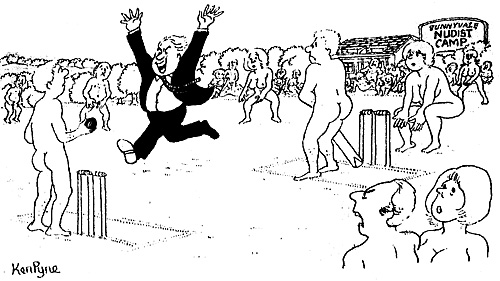

So what inspires cartoonists to focus on cricket? Ken Pyne produced Silly Mid-off, his wonderfully observed book of cricket gags, "because I was asked". And that's probably the case for the majority of scribblers. Newspaper pocket cartoonists have to respond to events with a gun to the head - and 'twas ever thus for the likes of the Express's Roy Ullyett, whom Trevor Bailey considered the greatest sporting cartoonist. There's nothing quite like a five o'clock deadline for summoning the muse at 4.55 p.m.

Few cartoonists' involvement with cricket has gone beyond spotting a chance to sell a drawing to pay for hard liquor. There are exceptions. Willie Rushton was an enthusiastic player for the Lord's Taverners, whose current president is Bill Tidy. Sir Bernard Partridge, Punch's political cartoonist before the Second World War, played cricket with J. M. Barrie and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (who himself once dismissed W. G. Grace). Pocket cartoonist Bernard Hollowood edited Punch from 1957 to 1968 and played for Staffordshire from 1930 to 1947. The tone of Punch's cricket cartoons was almost uniformly deferential: Mr Punch saluting Ranji as "A Prince of Cricket"; "Mr" Warwick Armstrong depicted as "The Lion Tamer", with a humbled British lion seeking his autograph; or Bradman towering over his English opponents in "Gulliver's Tour Among The Lilliputians (with Mr Punch's compliments to Mr Bradman)". All of which may have been fair and sporting, but wasn't exactly funny - and confirmed Punch as the voice of the Establishment.

My own enthusiasm for the game is matched only by my ineptitude as a player. But having drawn more cricket cartoons than Matt Prior has dropped catches, I've come to certain conclusions:

1. There are no jokes in England winning. For the cartoonist, England failure is far better than a Flintoff century or a Panesar five-for. In 1994, The Guardian's David Austin celebrated Brian Lara's historic 375 with him saying post-match: "I'd like to thank the England team, without whom…" Matt of the Daily Telegraph marked England's 2006-07 Ashes debacle by observing a genteel lady in a travel agent's. "My husband's in Australia watching the cricket," she says. "As a Christmas treat, I thought I'd fly him home." So, roll on more England disasters.

2. There's only one thing funnier than England failure - Australian failure. Particularly if they cry. Unfortunately that rarely happens, and I sadly can't find any cartoons of Kim Hughes blubbing, or Trevor Chappell bowling underarm. So we have to resort to jokes about Shane Warne's amusing hair or misdemeanours, and gags about Australian bowlers going out to nightclubs and texting nurses. The Aussie cartoonists can't think of anything else either.

The Ballarat Courier's John Ditchburn has drawn countless cricket cartoons - most seemingly about Warney. I've certainly yet to find anything else comical about Australian cricket.

3. Cricketers habitually behave badly. They cheat - hurrah! From balltampering to mysterious substances in the pocket, cricket has provided cartoonists with the materials with which to tweak their gags and get them through joke-blind editors and into the papers. Even better is bad behaviour on tour: upturned pedalos, jelly-bean incidents, love romps and broken beds. These are a cartoonist's slow full toss. So hats - and trousers - off to bounders everywhere.

4. Cricket is inherently absurd. It attracts streakers, men with beards dressed as nuns, thin men dressed as fat men dressed as Vikings, and occasionally fat men dressed as international cricketers.

So, if you want to draw cricket cartoons… forget it. There are far too many cartoonists as it is, the pay's lousy, and you have to deal with constant rejection. On the other hand, it gives you an excuse to watch cricket all day under the pretence you're scratching a living. What could be better?