Comfort blanket with a silver lining

Stephen Fay on a Lancastrian icon who bridged the north-south divide

|

|

|

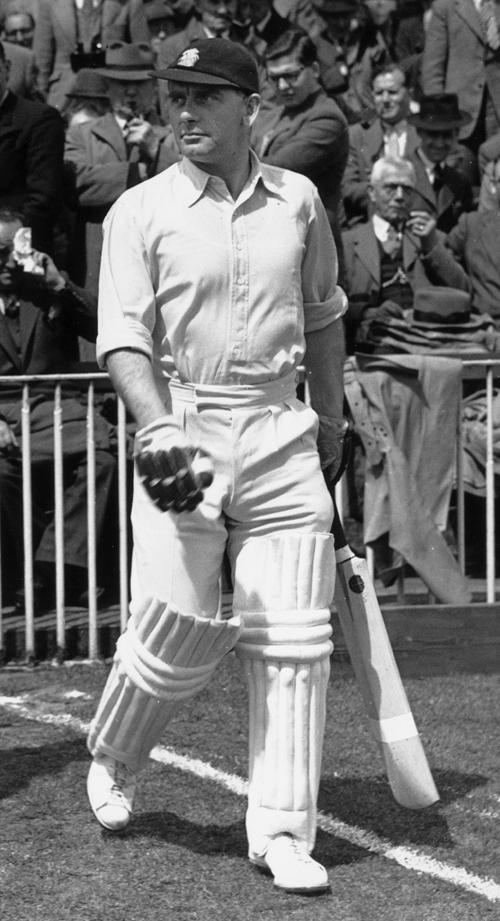

Cyril Washbrook is best remembered for a remarkable comeback, aged 41. He was a grand old man, a selector already, and his fellow selectors asked him to leave the room so they could decently pick him for the third Test at Leeds in 1956. These decisions can turn sour for both parties but Washbrook did not let his colleagues down. England were in dire straits at 17 for 3 when he came in to bat but he put on 187 with Peter May, who was barely a twinkle in the selectors' eyes when Washbrook had last played for England at Christchurch in 1950-51. At Headingley he was lbw, two short of a seventh Test hundred, and kept his place, playing in the Laker Test at Old Trafford, 19 years after his Test debut in 1937.

In a moment of exquisite agony for his fans Washbrook was out for 98. I was watching on television and I think it was probably the only time I saw him bat. As an eager nine-year-old I had been slipped into the press-box annex under the Grand Stand at the Lord's for the 1948 Test and I saw Don Bradman flickering to and fro for 89 and Sid Barnes hit the ball on to the old clock tower on his way to 141 but I did not see Washbrook bat. I must have seen him in the covers and I knew he was the best cover fielder in England. Everyone knew that.

When I was sneaked into The Oval later in the summer England were 42 for 6 but Washbrook was injured - a pity since he had scored 143 and 65 in the previous Test at Headingley to no effect. Australia's winning second- innings total of 404 for 3 was the record for 27 years.

But you do not have to watch a cricketer in the flesh to adopt him as a hero. I was in love with the idea of Cyril Washbrook. He was from Lancashire and, at the time I became aware of him, so was I. When our family moved to London in 1947, I needed to bring with me comfort blankets from a Lancashire childhood and Cyril Washbrook was my principal and prize icon. With Len Hutton he put on 359 at Johannesburg in 1948-49, which is still the fifth-highest opening partnership in Test history. Londoners were besotted by Denis Compton, all southern flash and dash, unlike Washbrook's northern application to his work. I basked in Washbrook.

Neville Cardus accurately described the Washbrook I choose to remember: "The chin, always square and thrust out a little, the square shoulders, the pouting chest, the cock of cricket cap, his easy loose movement, his wonderful swoop at cover and the deadly velocity of his throw in." Photographs normally show an unsmiling face, though it occasionally lapsed into a smirk. He was a fierce square cutter and a brutal puller and hooker, strong off his legs. (He was not so good at playing spin, it is said.)

Going to school in London, I felt especially proud that Washbrook's benefit in 1948 made him £14,000; that is £188,000 today - not enough for a Vaughan, a Flintoff or even a Ramprakash but at the time the biggest benefit by a large margin. (Even Compton raised only £12,200 in 1949.) It proved to me that Lancashire people appreciated quality and were generous with their money.

|

|

|

In fact, he had two remarkable strokes of luck. Lancashire gave him a fixture against the 1948 tourists as his benefit match and, when Bradman could have polished the game off in two days, he declined to do so and stayed around long enough on the third day to score a hundred in front of a full house.

I was reminded of this recently when I looked at Washbrook's autobiography, Cricket: The Silver Lining, which I originally acquired when it came out in 1950, perhaps after a visit to the dentist. My mother rewarded inadequate attempts to hide my naked fear with cricket biographies. It disappeared along the way but, when I saw the cover of Washbrook's book on the shelves of MCC's library, I remembered immediately the garish shades of green and red.

I had thought of him in various shades of blue, from purple to pale, in his great season in 1946 when he scored 1,021 runs between June 26 and July 17, while travelling 1,500 miles by slow coach and wandering train. One of my favourite cricket books is an account of Lancashire's 1946 season, Second Innings by Terence Prittie and John Kay. In it they write: "He should have been crippled by cramp, backache and indigestion. [But] Washbrook is hard boiled physically, tough mentally, full of Lancashire vigour and hardihood."

It seemed entirely proper that he should become Lancashire's first professional captain in 1954 and keep the job until 1959 when he was 45. He was the dominant figure and a dominating one. As captain he expected to be addressed respectfully and his team to be as neatly dressed as himself (his sleeves were folded "regimentally"). A barracker at Old Trafford tried to embarrass him by calling out "Come on, Mister Washbrook". But Mr Washbrook did not soften. Apparently he became a dour disciplinarian, impatient with cocky young men. But I understood that heroes are permitted to have feet of clay.

He died in 1999 and on August 8 during the Old Trafford Test match against New Zealand - the nadir of English cricket post-war - a minute's silence was observed before start of play, with the players lining up outside the pavilion's wicket gate, to honour a man they had probably hardly heard of. It was a grey morning. Not many spectators turned up and I think I was the only person to make the short journey from the press box to the pavilion. In an odd way it was the closest I ever got to Cyril Washbrook.

Stephen Fay is a former editor of Wisden Cricket Monthly and the author of Tom Graveney at Lord's - a Year at the Home of Cricket