After the ball

|

|

|

Whatever Steve Harmison goes on to achieve in cricket, he is likely to be remembered for one ball: the first bowled in the recent Ashes series in Australia that ended up in Andrew Flintoff's hands at second slip. Unfortunately Justin Langer had not got a touch. It was the widest wide in living memory.

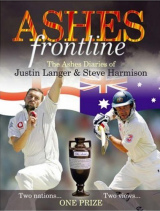

In a new book, Ashes Frontline, The Ashes Diaries of Justin Langer & Steve Harmison, Harmison writes just before the start of the series: "The tone of the last Ashes battle was set on the opening morning of the first Test at Lord's and we intend that to be the case again."

It certainly was, and not simply by the first hour or first over but by the first ball. Does Harmison have nightmares about it? "No, not really. It was something that just happened. I went up to bowl and the ball slipped out of my hand. These things happen. You have to put it behind you because you're still in a Test match." Does he feel the infamous ball did set the tone for the whitewash? "No, not really. I think that you're saying that because of what happened in the rest of the series." That is not strictly true. I am saying it because of what he has written in the book.

We meet in the spaceship media centre that hangs over Lord's. It is mid-March, freezing, thousands of miles from the heat of the Caribbean where Harmison would be spearheading England's bid to win the World Cup if he had not retired from one-day cricket and where all hell is breaking loose. Bob Woolmer, Pakistan's coach and former England batsman, has died and Flintoff, Harmison's great mate, has just been stripped of the vice-captaincy, after drunkenly capsizing a pedalo in the middle of the night and having to be rescued.

Harmison is glad he is not there. "I'm very happy where I am at this moment in time. I've not hid the fact that I don't like touring. There are other lads who have got kids in the same boat as me but people tend to use me as an example," he says. He is wearing a snazzy pin-stripe suit, dapper shoes, his hair is slicked back immaculately and he would not look out of place with a gun in his hand in a Prohibition-era movie.

It is only 18 months since Harmison was a national hero - our fastest bowler in the unprecedented pace attack (alongside Flintoff, Simon Jones and Matthew Hoggard) that beat the Aussies. Three years ago, after taking nine wickets in the final Test against West Indies at The Oval, he became No.1 bowler in the world rankings. Now he has fallen to No.17 in the world and his commitment has frequently been questioned by the game's experts.

It is not surprising, perhaps, that he is so defensive. He has a reputation for being chippy but today he seems to be carrying a sack of spuds on each shoulder. I ask him whether there were things England could have done differently in Australia. "Not really, to be honest. The thing was we got beat 5-0. I think Australia would have beat any team in the world 5-0 the way they were playing." But in his next sentence he says England gave the match away in the second Test and "lost the series in Adelaide in that mad hour we had. If we had got out of that with a draw, then we go to Perth after saving the game and the momentum's with us. It's a different series."

Could England have prepared better? "Preparation was fine. There was nothing else we could have done." The Australians might disagree with that; they found plenty to do, including compulsory attendance at a boot camp. Could he have prepared better? Yes, he says, he could have played in a warm-up in Adelaide but he was not fit and playing would have put him at risk for the rest of the series.

The criticism levelled most often against the management is that it did not give the team long enough to play themselves into form. Harmison will hear none of it, though. "It's disappointing that people are having a go at Duncan Fletcher," he says.

In the book, he says, poignantly, how much he felt for Marcus Trescothick, who was so distressed that he returned home before the first Test; he understood what Trescothick was suffering because he had been through a similar thing himself. Does he mean depression?

He gives me a blank look. "No," he says tersely. This is confusing. In the book Harmison writes: "I would prefer to have been injured than suffering in the way I did. You can't tell people what is wrong with depression. Only those who have experienced it know and there were a couple of times Marcus and I had a quiet chat because he knew I understood." It seems pretty unambiguous that he was talking about depression.

I ask how he came to write the book. "It came about when Marcus went home. He was writing a diary with Justin Langer and, when he went home, they asked me if I'd do it. I thought, 'Yeah, why not? I've not been involved in a book before.'" Did he have to be very disciplined to maintain the diary? "Not really. I've not read the book but what I'm hearing from the feedback of people who've glanced through it is that it's a pretty honest opinion of what happened."

Ah, perhaps this is why he and the book appear to be telling different stories: he has not read it. He says it so casually, without embarrassment or apology. The impression he gives is: why would he want to waste his time actually reading a book he has put his name to? This might be increasingly common in the world of sport but it is surely insulting to potential buyers, his fans, willing to fork out £12.99 on the diaries.

He admits that by the end of the series he did not even want to talk to his ghostwriter. "I was trying to hide and be a bit distant. Obviously we'd lost 5-0, so I didn't want to speak too much about that, but at the end of the day I had to because that was what I'd signed up to do." Harmison, 28, has always been regarded as an enigma - so often England's most pulverising bowler, regularly reaching speeds of 93mph, on occasion hitting 95, then at times horribly wayward. In the first match of the tour of Australia in 2002-03 he bowled seven consecutive wides - and 16 in the one-day match - against the ACB Chairman's XI. Yet he went on to terrorise the world's best batsmen.

He was almost as totemic in the 2005 Ashes victory as Flintoff. In many ways they were inseparable - best mates, twin prongs of the attack and terrible twins in celebration. At the culmination of the drinkathon it was Harmison who borrowed a pen and drew a beard and tache over the sleeping Flintoff's face and daubed the word "TWAT" on his forehead. When I ask him about it, it is the only time he almost smiles. "I did that, yeah. Unfortunately I did get the pen off somebody and went to town on his face. These things happen ..." He is so like Flintoff - huge, strong, bluff, working-class, rooted - but he lacks Freddie's easy charm. When I ask about his Ashington childhood he refuses to engage. What was he like at school? "I don't know, can't remember school days. It's a long time ago."

|

|

|

He concedes that he was a Newcastle United fan, more interested in football than cricket. "But football wasn't something I'd make a living out of. Cricket became something I took more seriously when I was 16 or 17 because it was something I could possibly make a living from." I notice a small vertical scar on his lip.

"Will you tell me the history of the scar?"

"No."

"Is it a cricketing scar?"

"No."

How did you get into cricket?

"Don't know to be honest."

"Did you have any expectations of what you would do in later life?"

"I don't know, I really don't know."

"What did your mum and dad do?"

"What's that got to do with the book?"

He stares at me.

"That's a really aggressive answer," I say. In 20 years of interviewing this is the first time anybody has refused to say what their parents did for a living. "Yeah, it's cos I really don't like the line you're going down."

"There isn't a line. I'm interviewing you about your life."

"I thought you were interviewing me about the book."

Silence...so I agree to interview him solely about the book he has not read.

In it he describes the horror of losing the second Test. England had been on top for four days, then imploded. At the end of the match some of the team popped into the Australian dressing room for a quick drink, he says, but ended up spending the evening there.

Did they have a good night? "It wasn't enjoyable because we lost but you had two teams working hard against each other and there's a realisation not that we'd messed up but a sense of disappointment at what happened. We didn't plan on staying there longer than a couple of beers but it was surreal what had just happened in the game. We just sat there and they couldn't believe they had just won the game and we certainly couldn't believe that we lost it."

It was hard to imagine the Australians doing the same in the reverse situation. After Allan Border's side lost in 1986-87 the Australia captain barely uttered a word to his opposite number in the next series, David Gower in 1989, until his team had wiped the floor with England and regained the Ashes.

But Harmison says it is natural for the players to hang out together after matches. They have so much in common, enjoy each other's company and anyway there is so much po-faced hypocrisy about drinking culture. Cricket has always been a drinking game, he says, and these days are much less so than, for example, the Botham era.

"The drinking culture probably has changed a hell of a lot since 20 years ago. Lads don't go out every night now. When they do go out they have a drink but at the end of the day these camera phones and technology we've got now we didn't have 20-odd years ago." There was, rightly or wrongly, an understanding back then between the media and cricketers. Now, he says, the players are in constant danger of being exposed by members of the public with a camera and a hotline to the red-tops.

|

|

|

He talks about how heavily the loss of the bowling coach Troy Cooley hit the team. Cooley, an Australian, asked for and was denied a two-year contract after England's Ashes victory. He was snapped up by Australia and is regarded as central to their victory and England's defeat. Harmison bowled at his best for England when Cooley was coach. "Troy was more than a bowling coach, he was more part of your family, more of a bigger brother than anybody else and that's nothing against Kevin Shine. Kevin is doing a decent job, a good job ... Troy and Michael Vaughan are similar characters in that they just know how to get the best out of people at any given time, whether it's a kick up the backside or to encourage you.

"Troy was always going to be missed and the way he left was totally disappointing for all of us - and where he went to. But there's not much we can say or do about it. At the end of the day Kevin Shine is the bowling coach now and we've got to work with him. I think he's doing a good job but Troy is someone who will always be held in high regard because of what he achieved with England."

After our little spat Harmison has calmed down and begun to talk more openly. Yes, he says, like Flintoff and most of the others he enjoys a drink at the right time and, yes, he is keen to put cricket into perspective. But that is very different from not caring: "A lot of people might disagree but cricket isn't life or death. But it hurts when you lose. It was devastating what happened in Australia. It disappoints me when people say I don't care about what I do."

"Why do they say that about you in particular?"

"I'm not sure. I do care about what I do. I've got this laid-back approach, I'm not somebody who shouts and rants and raves. I try and get on with my job as calmly as possible because I feel if you're relaxed you do your best." He has never been one for histrionics or hyperbole, whether on top as he was a few years ago or when he came crashing down. How did he feel when he was officially the No.1 bowler in the world? "I never really thought about it. I was doing a job for England. I'm not a massive one for personal gain, I try for the team. I got 10 wickets in the Ashes and we lost and I was devastated. If I'd got 10 wickets in the Ashes and we won, I would be jumping for joy."

For the first time I can see how much pain his and the team's fall from grace has caused him. "When I'm doing it well, I've got a big smile on me face and, when I was finishing the Ashes and doing not so well, it f****** hurts. And it does piss me off when they say you don't care about what you do." He says the last couple of years have been such an education; he is convinced he will never again experience the respective highs and lows of 2005 and 2006-07.

Now he says the important thing for him is to concentrate on his cricket and cement his place in the Test team and surge back up the world rankings. "I've retired from one-day cricket to try and play as many Tests as possible and I'm going to try and get back to enjoying it. I've not enjoyed the game as much as I'd have liked over the last 12 months. I had a year where everything went right a couple of years ago and last year it was probably one of the worst 12 months I've had. But at the end of the day I wouldn't swap it for anything." He pauses. "You've got to take the highs with the lows. It's a test of character."

Simon Hattenstone writes for The Guardian. Ashes Frontline, The Ashes Diaries of Justin Langer & Steve Harmison, is published by Green Umbrella in paperback at £9.99 Harmison is giving his royalties to The Bubble Foundation UK, based in Newcastle