It was fifty years ago today

The effect of the first Tied Test was to raise cricket from its prevailing grisly greyness and take it closer to the zeitgeist of that heady decade. That's why that game and that series remain unmatched for cricketing drama

Rob Steen

Dec 8, 2010, 3:21 AM

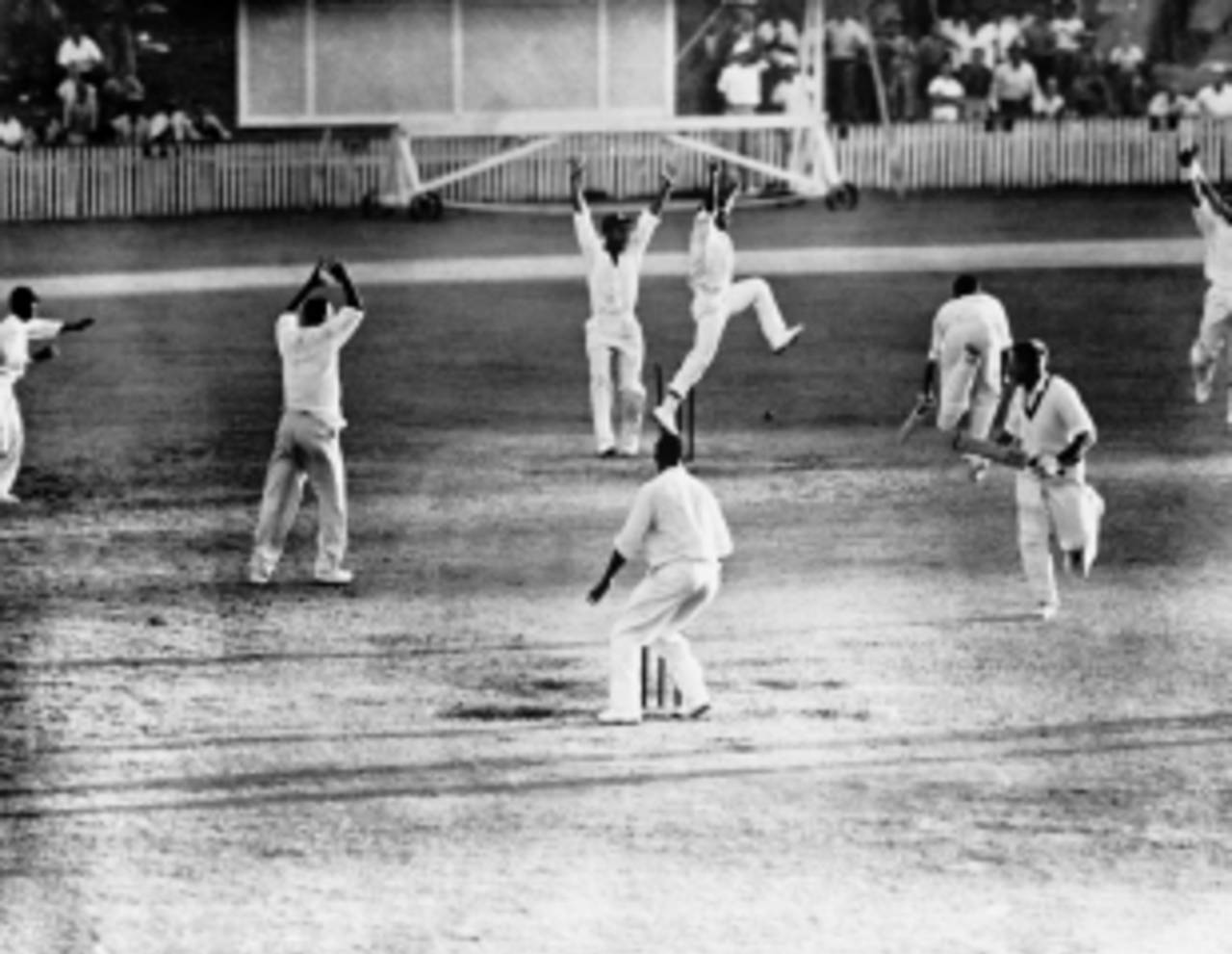

Joe Solomon ran out Ian Meckiff in the last dramatic act of a Test of outstanding quality • Getty Images

Brisbane 1960. Fifty years on, has any game touched it for aura or resonance? For resurrecting hope where virtually all had been extinguished? For giving future generations faith in cricket's potential as the most engrossing theatre of all? As that inimitable comedian Frankie Howerd was wont to put it, nay, nay, and thrice nay.

I was barely three at the time, and hence utterly unaware of a contest immortalised by the title of Jack Fingleton's vivid hard-backed account, The Greatest Test of All, but the ripple effect was vast. I was still in single figures by the time I learned about that magical first tied Test but the cumulative impression created by reports, memoirs, history books and monochrome photographs was deep and lasting. So this was how wondrous sport could be, how cricket could be.

Confirmation came in the late 1990s, via 59 minutes' worth of video highlights from ABC's television coverage. Sure, the view was largely from mid-off, the camerawork dodgy as well as prehistorically limited, but every frame was precious: the joyous majesty of Garry Sobers' cover drive as he flowed to his classical first-day hundred; Alan Davidson's consummate allroundedness; Norm O'Neill's power; Wes Hall and Rohan Kanhai in full exotic flight; the bedlam and mayhem that followed Joe Solomon's unerring side-on throw as Ian Meckiff lunged for the winning run. After 83 years and 502 games, the fanciful notion of a tied Test, the ultimate sporting longshot, had finally bounded from theory to reality.

As Gideon Haigh relates in The Summer Game, Keith Miller and Alan McGilvray, the commentator, were flying into Sydney together when the hostess advised them that the match had finished "even".

Miller: "You mean it wasn't a draw?"

Hostess: "No, it wasn't a draw."

Miller: "Then the West Indies won?"

Hostess: "No, nobody won it. I'll go back and find out."

By the time she returned with the full picture, McGilvray was the personification of misery. "I have spent nearly 25 years," he would write 25 years later, "being furious for leaving Brisbane that day."

Over those five days at the slow-blinking dawn of the 20th century's most progressive decade, Australia and the West Indies also gave us a blueprint: a three-day test of skill capped by a two-day examination of nerve, underpinned by a refusal to regard the draw as a worthy goal until all other options had been exhausted. And boy, was it needed.

IT WOULD BE HARD TO EXAGGERATE cricket's vices as the Fifties gave way to the Sixties. Chucking was rife. The West Indies banned Roy Gilchrist for hurling beamers at an Indian tourist. On successive England tours of the Caribbean, in 1954 and 1960, Tests at Kingston and Port of Spain erupted in riots. Bottles were thrown in Delhi too, impending home defeat the unifying cause.

Even more dispiriting was the grisly greyness of the matches themselves. Of the 11 dullest Tests in history (measured by run-rate when at least 20 wickets fell), 10 took place between January 29, 1954 and December 5, 1958 (and 17 of the 23 least gripping). Of the seven most dilatory days' play on record, five occurred between October 1956 and Christmas 1959. The most recent Ashes series, in 1958-59, began with the most patience-snapping, love-sapping passage in Anglo-Antipodean annals: England ground out 106 runs in five hours on day four at the Gabba, thanks primarily to Peter May's decision to promote Trevor Bailey ahead of Tom Graveney and The Barnacle's uncanny impersonation of a constipated slug. Not much of a plug for the first Test televised live down under. There have been easier times to be a cricket tragic.

The appreciation was entirely mutual: Melbourne expressed a nation's gratitude with a tickertape send-off. "The statement which was quite frequently made and which brought a lump to my throat and tears to my eyes," remembered Worrell, "was: 'Come back soon.' "

That Brisbane tie, therefore, could not have been timelier. What made it so magical, though, was its immediate legacy. The second and third Tests brought convincing wins for each side but the Hitchcockian suspense soon returned. Australia's final pair, Ken Mackay and Lindsay Kline, hung tight against Wes Hall, Garry Sobers, Lance Gibbs and Alf Valentine for the last 100 minutes to secure an impossible draw in Adelaide. Then, in the decisive bout in Melbourne, watched on the first day by a record throng of 90,800, Mackay, again, and Johnny Martin dragged the hosts across the line with two wickets standing and a few million hearts barely intact.

Revealingly, in each of those three epic encounters, first-innings leads were relatively minor - 52 in Brisbane, 27 in Adelaide and 64 in Melbourne. Each game built to a crescendo, a full and mighty climax. Fittingly, by way of reinforcing the wisdom of making Test matches the length they are, that MCG decider, scheduled for six days, finished late on the fifth.

Not until 2005 would a single series contain three such palpitating finishes. And not even the fused memory of Geraint Jones' plunging catch at Lord's, Brett Lee's doughty defiance at Old Trafford and Ashley Giles' eyes-agape cover-drive at Trent Bridge can quite match up to the delicious improbabilities savoured half a century ago, albeit probably because contemporary perceptions are so reliant on the interpretations of others, heightening the mystery and romance. That that trio of games raised the bar, and gave the planet's most anti-modern ballgame a tomorrow, cannot be disputed.

SERENDIPITY PLAYED ITS PART. The men who tossed up on December 9, 1960 were of a similar disposition. Richie Benaud and Frank Worrell were wise, enterprising enablers with an eye for big pictures and small details, but let's not paint them as romantics. Indeed, it was Don Bradman, not Benaud, who exhorted the baggy green 'uns to do their bit to drag the game from its negative spiral, a speech the captain would recall when the pair sat down for tea on the final afternoon. "[Bradman] looked quizzically at me and said: 'Well what's it going to be, Richie - a win or a draw?' "

Belatedly appointed as the islands' first full-time black captain, Worrell was taken aback by the crowds. "Never before had we experienced the pleasure of playing cricket in an environment in which the spectators regarded the quality of cricket as all-important whilst they seemed completely disinterested in the result of the game." The appreciation was entirely mutual: Melbourne expressed a nation's gratitude with a tickertape send-off. "The statement which was quite frequently made and which brought a lump to my throat and tears to my eyes," remembered Worrell, "was: 'Come back soon.' "

It would be a mistake, though, to imagine that this was a series founded on daring or enterprising batting, even by the slothful standards of the day. The most arresting statistics from this period are the scoring rates. The mean output was 2.65 runs per six-ball over; 56 bowlers were meaner than that, but then the batsmen, cautious to a fault, were all-too willing accomplices. How curious, then, that the rate during that Australia-West Indies series, 2.56, should have been under par.

The rest of the Tests during West Indies' tour of Australia in 1960-61 were also extremely watchable•Getty Images

Nevertheless, by way of affirming that a thick, twisting plot deserves the suspension of time rather than acceleration, Fingleton's conclusion was heady, even giddy. "By taking the corpse of international cricket out of its winding sheet and infusing new life into it; by converting what used to be cricket wars of attrition into joyous events…Australia and the West Indies have set an example which other cricketing countries will ignore only at the peril of their own cricketing status."

Little did Fingleton anticipate how freely that risk would be taken, even by the participants. "Dull and unenterprising cricket was over," claimed Benaud in A Tale of Two Tests, "in Australia at any rate." Within months of those words being published, however, came another meandering, drab Ashes tussle. "I think everyone who saw the last day at either Adelaide or Sydney felt that too great a disparity existed between what went on in the minds of the players, and what passed through the minds of the audience who had paid to be entertained," lamented Alan Ross. "Matches are played over five days," insisted Benaud, "not over one-and-a-half." Ted Dexter, his opposite number, suggested a purse of £1000 per match and cremating the Ashes.

Truth be told, that 1960-61 series merely bought the game some time. It would take Test cricket three decades to catch fire as Fingleton predicted. Even then, the chief influence was external, namely the mindset fostered by the one-innings variant. Now, in this era of unwearing pitches and unwavering bats and unhappy bowlers, with the international balance of power more widespread and even-handed than ever, with the draw having gone from norm to exception and with safety-first jettisoned in favour of safety-last, that 1960-61 blueprint is being followed.

The best sides arm-wrestle over the first three days whereupon the pace quickens and stronger minds prevail. Games are still being won on the opening day, when pitches are often at their least kindly, but day four is becoming increasingly pivotal - witness, in particular, October's Border-Gavaskar doubleheader in India. And turning deficits into victories is no longer a conjuring trick. Now it truly is a game of two halves, Richie.

ONE DIVERTING SUB-PLOT emerged between the fourth and fifth reels of that 1960-61 epic, when Fingleton, reporting for the Sunday Times, asked Worrell whether the rousing spirit could be maintained in the following summer's Ashes confrontation (it wasn't). Worrell, frank as ever, attacked what he saw as a crippling English disease, provoking a stern corrective from Gubby Allen. "[Worrell] said that they regarded the cricket field as a battleground; that their national characteristics had changed and they no longer got any fun out of cricket. He said they were much too serious about a game in which they didn't want to be beaten."

Might the same be said of Australia now?

Rob Steen is a sportswriter and senior lecturer in sports journalism at the University of Brighton